Drawing the anthropomorphic line: how human should your characters be? • Jonathan Emmett

Drawing the anthropomorphic line

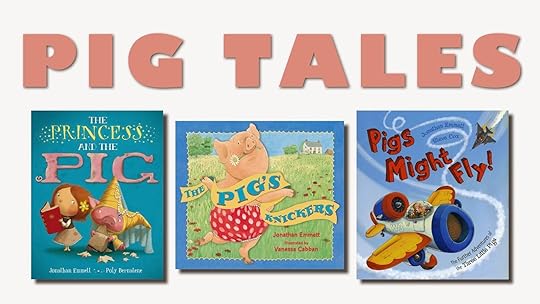

Drawing the anthropomorphic line The “Pig Tales” session I often do on my school and library visits features three picture books I’ve written about pigs. In between reading the three stories I explain that one of the things that makes them different from each other is how much anthropomorphism they use. I explain what this ridiculously long word means and why it’s such a useful tool for storytellers.

The dictionary definition of anthropomorphism is “the attribution of human characteristics or behaviour to a god, animal, or object.” I tell the children that anthropomorphism is simply “making something more like a person.”

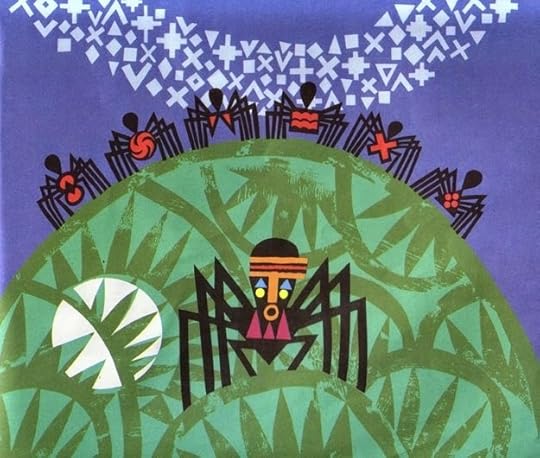

Many of mankind’s oldest stories come from Africa, the birthplace of the human race. In the African stories of Anansi the spider, Anansi thinks and speaks like a human and in some of the stories he takes on human form.

Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti by Gerald McDermott

Anansi the Spider: A Tale from the Ashanti by Gerald McDermottStorytellers have been using anthropomorphism – making animals think and talk like humans – ever since.

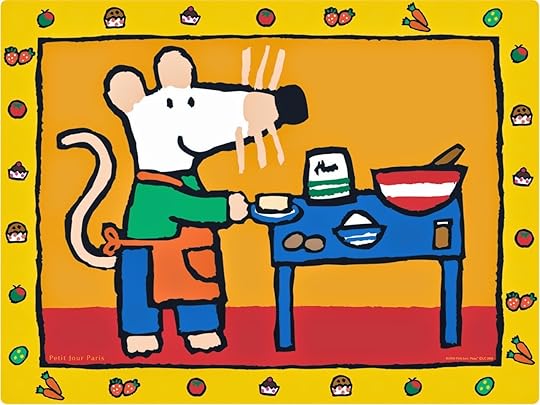

Lucy Cousins's Maisy Mouse

Lucy Cousins's Maisy MouseAnd it’s not just animals – you can anthropomorphise almost anything …

… vegetables …

… vehicles …

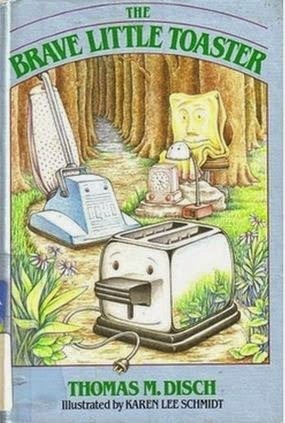

… even household appliances!

One reason storytellers use anthropomorphism is because people usually find characters more appealing if they think they are like them. Anthropomorphising an animal or even a toaster makes us care about what happens to them.

Anthropomorphism is not an either-or option; you can vary the amount you use. And, if you are creating a picture book, it’s worth taking the time to get the balance just right in both text and illustrations.

You can use varying amounts of anthropomorphism

You can use varying amounts of anthropomorphismMy picture book story Pigs Might Fly is a sequel to the traditional tale of The Three Little Pigs. The pigs in my story build and fly aeroplanes, so they are fully anthropomorphic – the story could just as well be about three humans. This was reflected in some of illustrator Steve Cox’s first character sketches for the book, where the pigs are fully clothed and one of them is carrying a phone and a laptop. However, the publisher felt that these characters didn’t have quite the right appeal, and the character designs that eventually appeared in the book wore less clothing and were more recognisably pig-like.

Some of Steve Cox's character sketches for Pigs Might Fly:

Some of Steve Cox's character sketches for Pigs Might Fly:Early, fully-anthropomorphic characters on the left and final characters on the right.

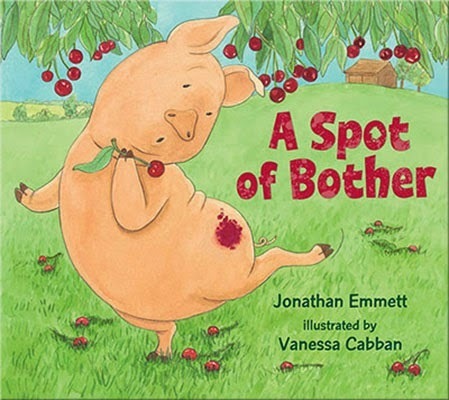

The pig in The Pig’s Knickers lives outdoors on a farm and – before the events of the story – would not usually wear clothing. However I made him talk, think and feel like a human in the text and Vanessa Cabban’s illustrations show him dancing on his hind legs and picking things up with his front trotters. As such, he’s a good example of a semi-anthropomorphic character.

One of Vanessa Cabban's illustrations for The Pig's Knickers

One of Vanessa Cabban's illustrations for The Pig's KnickersThe Princess and the Pig is the story of a piglet that gets switched at birth and is brought up as a princess in the mistaken belief that she has been bewitched. The running joke in the story is that, while the reader knows that Princess Priscilla is nothing more than an ordinary pig, the characters in the story don’t and spend all their time trying to make her look and behave like a human. When I first started thinking about the story I considered making Priscilla a little anthropomorphic, but in the end I decided that the story would be much funnier if I didn’t anthropomorphise her at all.

One of Poly Bernatene's spreads for The Princess and the Pig

One of Poly Bernatene's spreads for The Princess and the PigSo the next time you’re writing a story with animal* characters, take a moment to think about where’s the best place to draw your anthropomorphic line!

*Or vegetables or vehicles or household appliances!

Jonathan Emmett's latest semi-anthropomorphic picture book is

A Spot of Bother

illustrated by Vanessa Cabban and published by Walker Books.

Jonathan Emmett's latest semi-anthropomorphic picture book is

A Spot of Bother

illustrated by Vanessa Cabban and published by Walker Books.

Find out more about Jonathan and his books at his Scribble Street web site or his blog. You can also follow Jonathan on twitter @scribblestreet.

See all of Jonathan's posts for Picture Book Den.

Published on March 20, 2015 23:30

No comments have been added yet.