"Into the Woods" series, 37: Elemental Magic

In his famous "Doctrine of the Four Elements," the Greek philosopher Empedocles (5th century BC) divided the world into four elements associated with four divinities: earth (Hera), air (Zeus), fire (Hades), and water (Persephone). These four elemental "roots," wrote Empedocles, comprised not only the physical substance of all matter, but also the spiritual essences that quickened and animated all life forms. The universe, he explained, was comprised of two forces, Love and Strife, which wax and wane in strength. When Love was the dominant force, the four elements were balanced in a Sphere of Unity; but as Strife became dominant, the sphere was broken and the elements were scattered. The single immortal soul of Love was then divided into many, many souls (each containing some measure of Love and Strife), born and reborn into mortal bodies formed from the four elements. Though Strife remains dominant in the world, eventually its power, too, will wane, and Love will be on the rise once again. The elemental sphere will be restored, and the divided souls will meld back into One.

Aristotle later expanded on Empedocles' ideas in his influential Metaphysics. He wrote that all matter and all men are influenced by the qualities of the four elements: earth (dry and cold), air (wet and hot), fire (dry and hot), and water (wet and cold). Warmth and coolness, said Aristotle, are the most powerful of these qualities, making fire (whose primary power is warmth) and water (whose primary power is coolness) the most active and important of the elements. But because these two are opposites, they require the mediating qualities of a  third element (earth or air) in order to unite their properties. The mediating element is called the Harmonia (named after the daughter of Aphrodite and Ares), capable of binding opposites together in order to restore unity and health, to engender transformation, and to enable acts of magic.

third element (earth or air) in order to unite their properties. The mediating element is called the Harmonia (named after the daughter of Aphrodite and Ares), capable of binding opposites together in order to restore unity and health, to engender transformation, and to enable acts of magic.

One ancient way to create such a union was in the Pyria, the Greek equivalent of a Native American sweatlodge -- bringing earth, air, fire, and water together in a ceremonial setting. The Pyria, like a sweatlodge, was made of blankets stretched over a wooden frame. Stones (earth) are heated (fire), then placed in a cauldron inside the Pyria, where water is poured over them, forming steam representing the union of all four elements. As John Opsopaus writes (in Bibliotheca Arcana), the steam "is the (Hot, Wet) Air that unites the opposites. This all takes place in contact with, or even within, the (Cool, Dry) Earth." In Native American sweatlodge ceremonies, the elements of earth, air, fire, and water are also united in the service of prayer, purification, and spiritual transformation. The exact form of the ceremony varies from tribe to tribe, but it is generally common for the activating spirits of the four elements to be respectfully addressed as living beings and honored for their crucial role in sustaining life upon the earth. The hiss of the water on hot stones, sending steam to fill up the dark of the lodge, is said to represent a child's very first breath -- air, earth, water, and fire united as new life begins. The Lakota word for the sweatlodge ceremony, inipi, literally means "to breathe."

The ancient Celts divided the world into three sacred elements, with earth, water, and air as the swirling spirals of the tri-part triskele symbol. The Norse had four primary elements: fire, ice, wind, and wave, to which (some believe) they added four secondary elements: iron, salt, yeast, and venom -- with a ninth element, earth, formed from a combination of all the others. The classic Tarot deck is based on a system  of four, with Coins representing earth, Cups representing water, Swords representing air, and Wands representing fire. The Chinese recognize five basic elements: earth, water, fire, wood, and metal, as does Achaemenid Zoroastrianism in Arabic lands: earth, water, fire, plants, and metal. The Indian Chandogya Upanishad names just three elements: earth, water, and fire.

of four, with Coins representing earth, Cups representing water, Swords representing air, and Wands representing fire. The Chinese recognize five basic elements: earth, water, fire, wood, and metal, as does Achaemenid Zoroastrianism in Arabic lands: earth, water, fire, plants, and metal. The Indian Chandogya Upanishad names just three elements: earth, water, and fire.

In alchemy, the union of fire (masculine) and water (feminine) is one the primary tasks of the art, made possible through the mediating elements of air and earth. Though alchemy is often perceived now only as a crackpot pseudo-science through which men sought to turn lead into gold, mythic scholar Mircea Eliade pointed out (in The Curcible and the Forge) that alchemy as it was practiced long ago was as much a philosophy as a science. Alchemy, according to Eliades, arose from the early Mystery rites of the ancient Craft Guilds of metallurgists and smiths -- which, in many cultures, had initiatory practices similar to those of shamans or wizards. For alchemists through the centuries, transmuting "lead" into "gold" was not a literal but a spiritual process, akin to seeking enlightenment. Alchemical experiments in the laboratory were, on the one hand, an early form of the secular science of chemistry -- but they also had a distinctly sacred aspect, drawing upon Aristotelian, Chinese and other ideas about the sacred qualities of the elements. Alchemists sought to bring the elements together into perfect states of unity as a means of sustaining health, longevity, and spiritual growth.

"I had discovered, early in my researches," wrote William Butler Yeats (in Rosa Alchema, 1913), "that their doctrine was no mere chemical fantasy, but a philosophy they applied to the world, to the elements, and to man himself."

Many other systems of magical belief were also rooted in the four elements. Wizard, witches, and enchanters of all stripes called upon the power of fire (associated with passion), water (the emotions), earth (the body), and air (the mind and imagination), or sought to communicate with magical spirits linked to each element.

Earth elementals included those who lived in caves, barrows and deep underground, and who often had a special facility for working with precious metals. Such creatures appeared in myths and legends worldwide,  including the Coblynau in the hills of Wales, the web-footed Couril guarding the standing stones of Brittany, the various metal-working dwarves of Old Norse legends, the Maanväki of Finland, the Thrussers of Norway, the Karzalek of Poland, the Erdluitle of northern Italy, the Illes of Iceland, the Gandharvas of India, and the Gans of the Apache tribe in the American South-west. Forest fairies of all shapes and sizes were also associated with the element of earth, such as the shy Aziza in the woodlands of West Africa, the Mu of Papua New Guinea, the Shinseen of China, the Kulaks of Burma, the Hantu Hutan of the Malay Peninsula, the Bela of Indonesia, the Patu-Paiarehe of the Maori in New Zealand, the Oakmen of the British Isles, the Silvanni of in woodlands of Italy, the Skogsra (forest spirits) of Sweden, the Ulda of Sámi tales, and the Manitou of the Algonquin tribe in the forests of Canada.

including the Coblynau in the hills of Wales, the web-footed Couril guarding the standing stones of Brittany, the various metal-working dwarves of Old Norse legends, the Maanväki of Finland, the Thrussers of Norway, the Karzalek of Poland, the Erdluitle of northern Italy, the Illes of Iceland, the Gandharvas of India, and the Gans of the Apache tribe in the American South-west. Forest fairies of all shapes and sizes were also associated with the element of earth, such as the shy Aziza in the woodlands of West Africa, the Mu of Papua New Guinea, the Shinseen of China, the Kulaks of Burma, the Hantu Hutan of the Malay Peninsula, the Bela of Indonesia, the Patu-Paiarehe of the Maori in New Zealand, the Oakmen of the British Isles, the Silvanni of in woodlands of Italy, the Skogsra (forest spirits) of Sweden, the Ulda of Sámi tales, and the Manitou of the Algonquin tribe in the forests of Canada.

Air elementals included all manner of winged fairies, sprites, spirits, and sylphs, such as the luminous Soulth of Irish lore, the Star Folk of the Algonquin tribe, the Atua of Polynesia, and the Peri of Persia (said to dine exclusively on perfume and other delicate scents). Creatures who accounted for weather phenomena (mistral winds, whirlwinds, storms, etc.) were also associated with the air element, including the Spriggans of Cornwall, the Vily of Slavonia, the Vintoasele of Serbia and Crotia, and the Rusali of Romania.

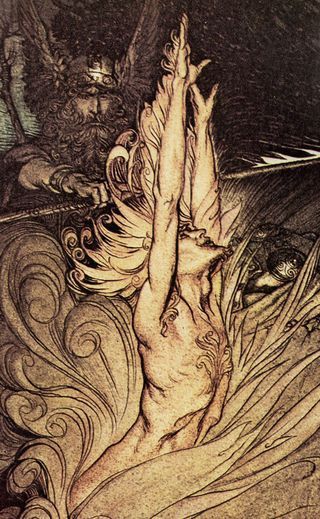

Water elementals were divided between those of the sea and those of fresh water. Salt water elementals included mermaids and mermen, seal people, and sirens of various kinds: the Selchies (Selkies) of western Europe, the Daoine Mara and Fin Folk of Scotland, the Merrows of Ireland, the Nereides of Greece, the Havfreui of Scandinavia, the Mal-de-Mer of Brittany, and Groac’h Vor, a Breton mermaid. Fresh water elementals lived in rivers, lakes, pools, fountains, bogs and marshes, and anywhere else that water was found. These included the nixies and kelpies of English rivers, the Dracs who haunted the rivers of France, the Rhinemaidens of Germany, the  Kludde of Belgium, the Laminak of the Basque region, the Hotots of Armenia, the Judi of Macedonia, the Cacce-Halde of Lapland, the sweet-voiced Nakk of Estonia, and the bashful Nokke who appeared only at dusk and dawn in Sweden.

Kludde of Belgium, the Laminak of the Basque region, the Hotots of Armenia, the Judi of Macedonia, the Cacce-Halde of Lapland, the sweet-voiced Nakk of Estonia, and the bashful Nokke who appeared only at dusk and dawn in Sweden.

The most common type of fire elemental was the salamander, much prized as a spirit-helper by witches, wizards, and alchemists even though they were tricky, quick-tempered creatures, often appearing as blazing sparks of light by those who sought their aid. Also aligned to the fire element were treacherous Djinn of Persian lore, the seductive Muzayyara in Egyptian tales, the Akamu of Japan, and the Drakes or Drachen of western Europe (who resembled streaking balls of fire and smell like rotten eggs). Luminous will-o'-the-wisp type fairies were also classified as fire spirits -- such as the Ellylldan of Welsh marshland, the Teine Sith of the Scottish Hebrides, the Spunkies of southwest England, the Faeu Boulanger of the Channel Islands, the Candelas of Sardinia, and the Fouchi Fatui who haunted marshes, ponds, and cemetaries in northern Italy. The various fairies, brownies, and trolls who guarded hearth fires (the Dĕduška of Russia, the Gabija of Lithuania, the Natrou-Monsieur of France, etc.) could be either malign or beneficent, depending on their country of origin and the circumstances under which they were encountered, but most other fire elementals were exceedingly dangerous and best left alone.

Earth, air, fire, and water: these four elements, in the Western tradition, are the foundation of natural magic, alchemy, philosphophy, modern science, and life itself. "Life is the fire that burns and the sun that gives light," said the Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger. "Life is the wind and the rain and the thunder in the sky. Life is matter and is earth, what is and what is not, and what beyond is in Eternity."

Likewise, an old Navajo prayer honors the elements and our connection to all things formed of them: "The mountains, I become a part of them. The herbs, the flowers, the trees, I become a part of them. The morning mists, the clouds, the gathering waters, I become a part of them. The thunder, the flash of lightning, the sacred fire, I become a part of them. The wind, the cedar smoke, the living breath, I become a part of them. As I rise in the morning, I am part of them. As I pray in the morning, I am part of them. In beauty, I am part of them. In this way, I am part of them. "

Further Reading

Nonfiction (online): Heinz Insu Fenkl examines fire myths in "Fire and the Fire Bringer" and discusses the mythic/linguistic history of "Men and Mud" (Journal of Mythic Arts); I explore water myths in "Water, Wild and Sacred" (Myth & Moor); and David Abram meditates on air in "The Air Aware" (Orion Magazine).

Fiction (print): I highly recommend the "Elemental Logic" series by Laurie J. Marks, which is deeply steeped in elemental magic and folklore. The first three books of the series -- Fire Logic, Earth Logic, and Water Logic -- are now available in beautiful editions from Small Beer Press. (The fourth book, Air Logic, is forthcoming, but each book stands perfectly well on its own.) Marks is writing "imaginary world" fantasy better than just about anyone else these days, inviting comparisons with Ursula Le Guin, Elizabeth Lynn, and C.J. Cherryh for the depth and complexity of her work.

Water and Fire, the first two books in the on-going 'Tales of Elemental Spirits" series by the husband-and-wife team of Peter Dickinson and Robin McKinley, contain delicious short stories by two of the best writers in the fantasy field. A.S. Byatt's Elementals: Stories of Fire and Ice is also enchanting, although the link between the stories and the collection's title is a little less direct. For children, Earth, Fire, Water, Air by Mary Hoffman is a truly splendid gathering of world-wide myths, folktales, poems and musings on the elements and our connection to nature, with lovely illustratons by Jane Ray.

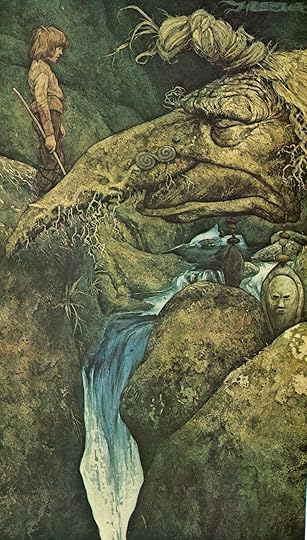

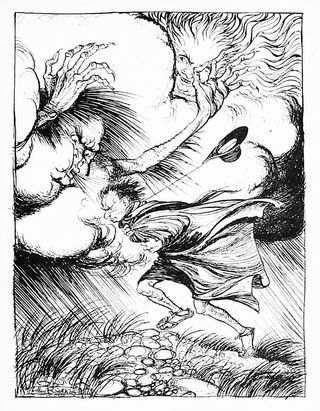

Art above: "The River Teign" by Brian Froud. "The Shipwrecked Man, the Wind, and the Sea" and"The North Wind and the Sun" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). "Dreaming" by Brian Froud. The Neolithic triple spiral (triskele) symbol. "The Alchemist" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). "Mime Makes a Sword for Sigfried," "Twilight Dreams," "The Rhinemaidens," and "Appear Flickering Fire" by Arthur Rackham. "Will'o the Wisps" by Brian Froud. "Undine" by Arthur Rackham. "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918). The cover art for Fire Logic and Earth Logic is by Kathleen Jennings.

Art above: "The River Teign" by Brian Froud. "The Shipwrecked Man, the Wind, and the Sea" and"The North Wind and the Sun" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939). "Dreaming" by Brian Froud. The Neolithic triple spiral (triskele) symbol. "The Alchemist" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953). "Mime Makes a Sword for Sigfried," "Twilight Dreams," "The Rhinemaidens," and "Appear Flickering Fire" by Arthur Rackham. "Will'o the Wisps" by Brian Froud. "Undine" by Arthur Rackham. "Trolls" by John Bauer (1882-1918). The cover art for Fire Logic and Earth Logic is by Kathleen Jennings.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers