The Art of the Collage: Visions of Excess

If you don't follow the art world -- which is its own thing separate from the art itself -- you may not know that the collage has made something of a comeback. First appearing in the early 20th century, the term derived from the French "coller" and was coined by both Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso.

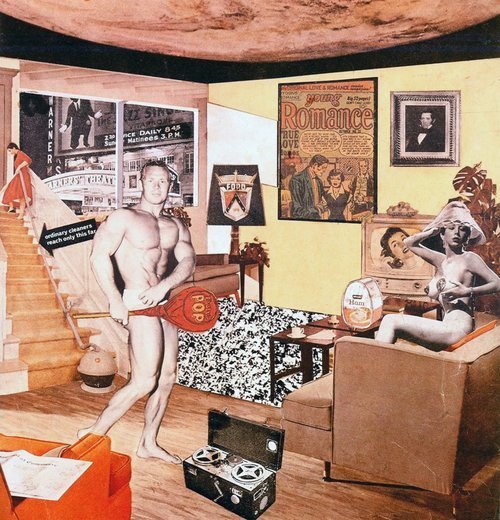

As a distinct form, collage developed alongside other modernist movements (like Dada) and persisted into the pop art movement of the 1950s and 60s. In fact, the first iconic work of pop art is Richard Hamilton's Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? which appeared in 1956.

But after mid-century, collage largely devolved to handicraft, worthy only of elementary school scrapbooks (or so one would have been told), probably because of the medium's popularity and the ease with which it could be replicated. There were exceptions of course -- there always are in art -- but for most of the last four decades, collages were not regularly being shown and sold in galleries, nor collage artists being featured in contemporary art magazines.

Recently all that has changed. One can give any number of reasons, but I blame hipsters, particularly their fascination with upcycling and irony.

But like most things these days, it starts with this thing you're on. The Internet.

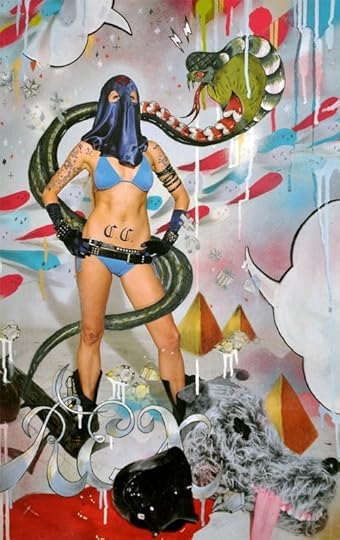

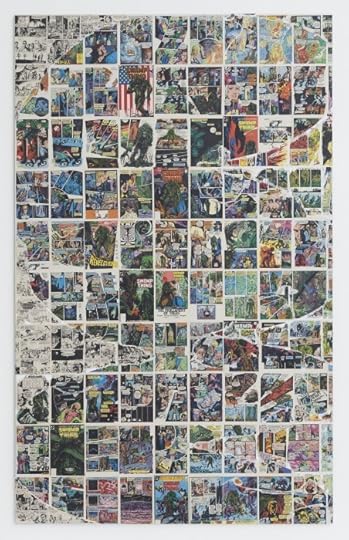

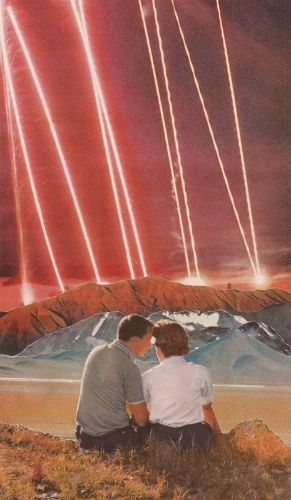

Cobra Command by Morgan Slade

We shouldn't underestimate the power of the internet to play on the collective psyche. Not only do we have well over a century of mass produced media -- particularly periodicals, which is where much of the fodder for collage comes from -- but in the last 25 years, most of it has been brought online. Even where something has yet to be digitized, it is likely to have been collected, indexed, and sold on sites such as eBay.

All that means we are aware of ourselves as no previous culture has been, and through our collected access to all the magazines, books, movies, albums, advertisements, news reports, pornography, political speeches, plays, TV shows, toys, games, home appliances, automobiles, and hair care products, we are aware of ourselves first and foremost as a culture of excess.

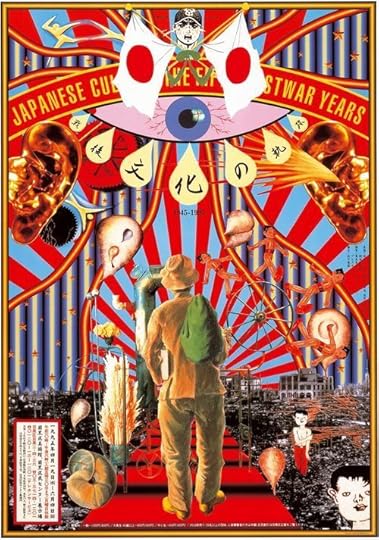

Michael Waraksa

No format celebrates excess better than collage.

But it is precisely because we are so aware of ourselves that, as observers, we cannot participate in art directly (as previous cultures did). When we look at a painting, we are aware that we are looking at a painting, we are aware of art theories which describe both the painting and our looking at the painting, and we are aware of the history of both painting and of art theory.

This is true ESPECIALLY if you know nothing about art. That's because the relevant bits are likely to have been neatly summarized for you on a plaque on the wall, or in the handy fold-out museum guide, or in the automated audio tour that came with an upcharge. Such summaries tell you, even where you don't understand them, that viewing art is a complex activity with a long history and probably a bunch of science behind it. And stuff.

Like the high school student who employs sarcasm to mock whatever she lacks the confidence to participate in, we don't allow ourselves to appear unsophisticated, to drop below the "meta-level" of theory and criticism, to be the object of description -- museum-goer, art viewer, naive actor -- rather than the author of it. Thus we can only experience art ironically.

[image error]

"In the Pavilion of the Red Clown" by Robert Williams

[image error]

"When Fairy Tales Collide" by Todd Schorr

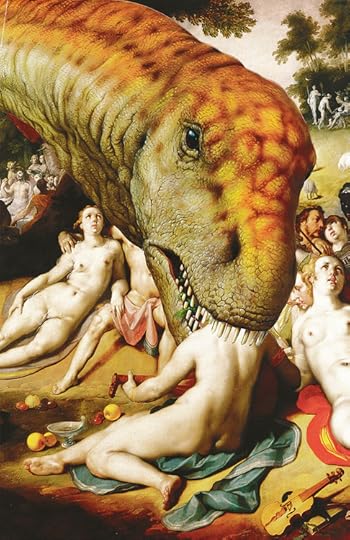

You can see the precursor to the freneticism of collage in the works of artists like Robert Williams and Todd Schorr, whose paintings appropriate cultural icons to ironic effect. (Mickey Mouse seems to be a favorite target.)

Collage takes this one step further by dropping the interpretive act -- paint and brush -- and using the detritus of the culture of excess (collected and indexed thanks to the internet) as the medium itself. Arranging magazine clippings is a way of serving our refuse (upcycled!) back to us as if to say, "see what we've become?"

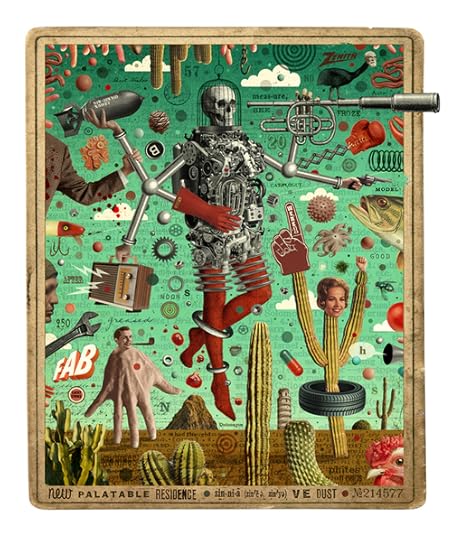

Eduard Bezembinder

For example, take the work of Eduard Bezembinder, who combines the "low brow" cultural detritus of mass produced, pop culture printing with (the equally mass produced) reproductions of old "high brow" art, which is an effective if less-than-subtle reminder of what we lost.

That's not to say there aren't highly original works of art being produced today. There are. More than ever. (And if you follow my streams on social media, you've seen quite a bit of it.) Nor am I suggesting a collage itself isn't original. Of course it is. As much as anything else.

What we've lost is not the ability to make great art but rather to experience it naively.

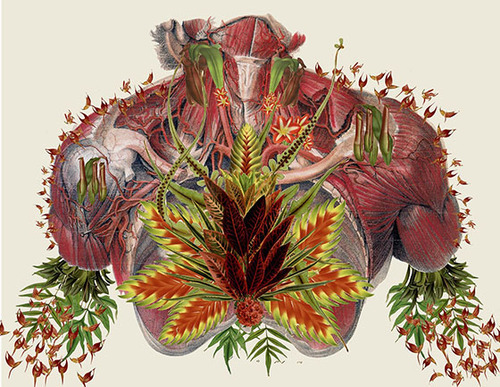

Travis Bedel

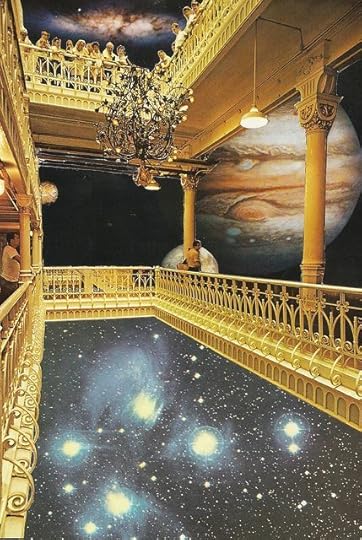

Nikolas Gambaroff

Alfred Steiner

Eduard Bezembinder