Formative Years

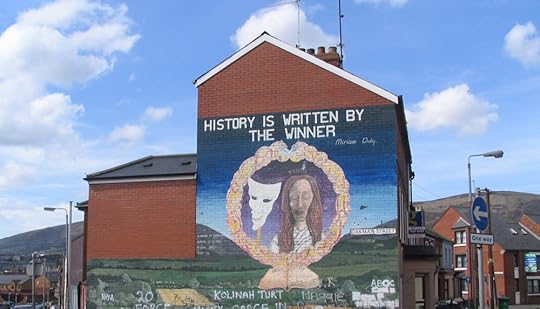

I never met Miriam Daly. She was brutally murdered when I was only seven years old. Indeed, even if her life hadn’t been cut short, the chances of us ever meeting was slim. After all, I was growing up on the other side of the wall that divided our communities. Those responsible for her murder broke into her home on 26th June, kept her captive and waited for the return of her husband so that both could be executed. When they realized that he was in Dublin they shot her before fleeing.

Miriam was a founding member of the Irish Republican Socialist Movement, becoming chairperson after the assassination of Seamus Costello. She was also a prominent activist in the civil rights movement, a key member of the Northern Resistance Movement, part of the Prisoners’ Relatives Action Committee, and sat on the national Hunger Strike Committee,. During this time she was also vocal in opposing Sinn Féin’s move towards federalism.

She was a gifted communicator and academic who could easily have stayed within the safe confines of university life, but who instead became involved in grass-roots politics during some of the darkest and most dangerous days of the conflict. A controversial figure, Miriam spoke out against any talk of peace and reconciliation that implicitly maintained structural injustice. A commitment reiterated by her husband of the 25th anniversary of her death,

“I feel there is at least one thing I can do, and that is to restate an important message she never tired of repeating. It was: to beware of and shun so-called ‘conflict resolution’, the alleged academic discipline which is in fact an imperialist confidence trick.”

I never met Miriam Daly, but I did meet her husband, James Daly. Indeed he became one of the most important and lasting influences in my life. James initially helped show me the importance of theory, and then became my most influential teacher. As a deeply committed Marxist it didn’t matter what course he was teaching. Like salmon returning to their breeding ground, our classes would invariably find their way back to Marxist dialectic. Lectures rarely started on time, and a one hour class would regularly turn into a three hour discussion with blackboards full of esoteric scribblings that took on the aura of scriptural truth for his students.

His passion was, and I am sure still is, intoxicating, and often spilled over in surprising ways. For instance, I remember sitting in a pub with other students one afternoon, listening intently to him discuss Marxism and Scholastic thought in a way that made it feel like the future of the world somehow rested on this subject. In mid sentence a student picked up his phone to answer a call. James instinctively reached out, grabbed the phone and deposited it in the student’s pint without stopping his train of thought.

We all accepted these (not uncommon) events because we knew that we were in the presence of a real thinker. He accepted people from both sides of the political divide. And he didn’t just teach us about justice, he inspired us to enact it. In fact he had a reputation for creating engaged disciples in the university, something I discovered when studying for a Master’s Degree in the Politics department. There I learned that the lecturers had a name for James’ students, those militants who opposed postmodern thought and liberalism at every turn: Dalyites.

At a time when Queens University was transitioning from a place of learning to an industry for the creation of workers, James fought at every turn. He defied every rule and protected the intellectual credibility of the department as best he could. He would tell his most committed students to ignore word limits, write on their passions, and take positions (with the proviso that they wouldn’t tell the department secretary and instead slip the essays under his door while no-one was looking).

One time, when I was sitting perplexed in a huge, austere exam hall, he tapped me on the shoulder and asked if everything was OK. I told him that I was hoping to write on Heidegger, but that there was nothing about him on the paper. He looked at me and said, “you know, I’d love to hear your thoughts on this,” then he glanced up for a moment, took a pen out of his old jacket, and scratched a Heidegger question onto my paper (I didn’t answer it though, fearing that the university would use it against him).

He dedicated himself to teaching and eschewed the university pressure to publish with well known academic houses; choosing instead a tiny publisher run by a former student. He put teaching first, was in constant battle with the analytic department (Queens was one of the few universities that had both an analytic and scholastic department – now it has neither) and was a thorn in the flesh of the academic authorizes – who eventually forced him out.

I never met Miriam Daly, but I encountered some of her spirit in the husband she left behind. A spirit that has provided me with a standard to admire and aspire to. Miriam remains a controversial figure, but regardless of where one stands with regard to her politics, she shows us what commitment to a cause you believe in looks like, and what such a commitment might ultimately cost.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers