Of Protons, Neutrons, and Shrodinger’s Cat

How much is enough?�� And how much is too much?�� These are questions every writer must wrestle with at some point or another.

Let’s say an idea strikes.�� It hits you, unannounced, perhaps as you’re walking the dog or lying half-asleep in bed, the sounds and silences of the night enveloping you like a warm, familiar blanket.�� Maybe you’re out jogging or playing a tennis match.�� Ideas are funny that way.�� They often come at the oddest, most unexpected of times.

But this particular idea, this hypothetical kernel of excitement, also carries with it a hefty helping of intimidation.�� Not so much due to the story itself, or the characters–they’re the aspects that are so exciting, after all.�� No.�� It’s the research.�� The subject matter.�� The amount of know-how that must be present to write about the topic intelligently.

“Write what you know,” is a maxim every writer is familiar with, and to a degree, it’s true.�� We can only create from our point of view, from our own unique and perhaps even idiosyncratic vantage point of the world and the people who inhabit it.�� But does that mean we can’t write about the past?�� Bygone eras?�� Or what about the future?

What about “ghost girls” with swirling blue eyes who are able to pull four seventh-grade boys into a parallel dimension?

Are these ideas somehow off-limits to us?�� Of course not.�� This is why the “write-what-you-know” edict can be constraining if applied too literally.�� There is nowhere our imagination cannot take us.�� No star is too far away.�� No date too distant.�� No world too remote.

But what about the details of said world?�� What about the nuts and bolts of the journey to that star?�� How much actual history do we incorporate into our period-piece novel?�� How much science do we put into our science fiction?

Admittedly, genre does play a part.�� After all, it’s possible the plot of a historical novel will revolve around an actual event–perhaps the sinking of the Titanic or the First World War, or any of a number of a million other possibilities.�� In such a case as this, the historical details are crucial to the flow and outcome of the story.

Even in the realm of science fiction, there are no hard-and-fast rules.�� Some stories, by their design, their makeup, subject matter, and perhaps even intended audience, will be more technical in nature.�� Whether we are dealing with a period-piece romance set in 19th-century France or a futuristic, galaxies-spanning epic, however, no fictional story can afford to get too bogged down in the minutiae of the subject matter.�� A novel is not a textbook.

But how much is too much?�� Do we really need to do copious amounts of research?�� Does an author need to be a subject-matter expert to be able to write adroitly about a particular topic?

Or can you get away with simply winging it?

As with so many things, I believe the answer lies somewhere in the middle.

**************

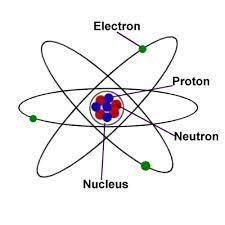

When I wrote The Eye-Dancers, I realized early on that I had a challenge on my hands.�� While there is a significant fantasy aspect to the story, I also intended to incorporate an element of pure science fiction, as well.�� I didn’t want every otherworldly twist and turn to be nothing more than a product of the imagination.�� After all, parallel-worlds theory is not merely relegated to the fictional.�� There were some fundamental quantum-mechanics principles at play here.�� The question was:�� How to incorporate them into the fabric of the story?�� And did I even know enough about quantum physics to attempt this?�� I had always enjoyed a fascination with alternate universes, and had long dabbled in scientific literature.�� I knew my protons from my neutrons and electrons!�� But I was far from an expert.

So . . . I decided to read up on quantum physics.�� I researched online and read a few books, making sure I at least had some understanding of the basics.�� I learned much more on the topic than I would use in the novel–but that was by design.�� I was more comfortable trying to pick and choose selectively from a base of knowledge as opposed to blindly groping for random, low-hanging quantum fruit.

But I knew the quantum-physics aspect of The Eye-Dancers needed to be judiciously utilized.�� The goal was to sprinkle it in and scatter it throughout the story like finely dispersed particles of stardust.�� At no point did I want a reader to feel bogged down.�� Rather, with hope, the quantum principles would enhance the story, make it more interesting, and attempt to give a (at least somewhat feasible) scientific rationale to a fantastic series of events.

One advantage I had was the character of Marc Kuslanski, the precocious science wiz.�� Throughout the novel, it is Marc who gives voice to the quantum-physics possibilities.

For example, shortly after the boys arrive in the variant town of Colbyville, Marc, after a brief reference to Shrodinger’s Cat,�� a quantum-mechanics thought paradox, explains the concept of parallel worlds . . .

“‘Everything in existence fits together,’ he said.�� ‘The smallest subatomic particle, the worst hurricane, the largest whale, the layers upon layers of reality.�� All of it.�� And what quantum mechanics tells us is–there are infinitely multiple versions of each of us.�� Infinitely multiple versions of our own earth.�� You couldn’t even begin to count them all.”‘

His logic-oriented views of the universe may not always be right.�� But they serve as a counterpoint to, as well as a conceptual explanation of, the paranormal events he and the other protagonists endure.�� In this way, Marc discusses the rational behind the irrational, the theoretical behind the random, the science behind the fantastic.�� Some of his hypotheses, rigid as they are, unwilling to account for those phenomena beyond the purview of science, may not always be true.�� But hopefully they provide an additional layer, an interesting nugget, to the plot.

************

“A little learning is a dangerous thing,” British poet Alexander Pope once wrote.�� And that may be the case, much of the time.�� But for novelists, “a little learning” can be the difference between a believable story and one that doesn’t quite ring true.

Or, put another way:�� There is always room for Erwin Schrodinger’s theoretical feline.

Thanks so much for reading!

–Mike