Deep Habits: Work With Your Whole Brain

Surprising Understanding

Last summer, I wrote a post detailing various strategies for reading mathematical proofs faster.

Last week, I stumbled across a new strategy that I think may be relevant for many different types of deep information processing.

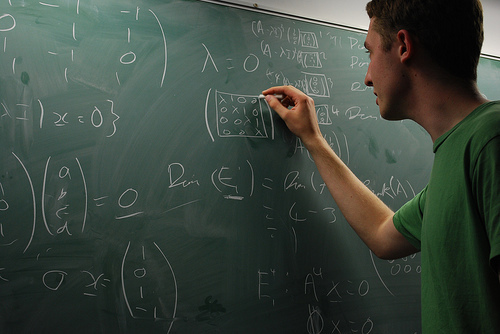

I came across this strategy while peer reviewing a complicated computer science paper. As I read, I quickly became frustrated. I was processing lemmas and theorems, one by one, but as the details for each slipped from my short term memory to make room for the next, there was no sense of a coherent whole. It was as if I couldn’t get my metaphorical arms around this mathematical beast.

After an hour of this blind processing I decided to step back and try to summarize what I understood so far.

It was here that things got interesting.

As I wrote, I discovered to my surprise that I actually understood way more than I expected. My short summary stretched into a longer digression on the problem, why it was hard, what their technique did differently than previous results, and, in the final accounting, where the real contributions could be found.

To be clear, I didn’t have the math all worked out. If you asked me to recreate all the proof details, I couldn’t. But somehow during my frustrated slog from one step to the next, another part of my mind was dutifully collecting and organizing the pieces — work which didn’t become apparent until I tried to write down what I knew.

New Thoughts on Thoughts

Not long ago, when researching a yet to be announced new writing project, I stumbled into a large research literature on what is sometimes called Unconscious Thought Theory (UTT). At the core of UTT is the following idea: the parts of our brain supporting conscious thought represent only a small fraction of our neuronal horsepower. When it comes to complex tasks, therefore, our conscious attention can help intake and understand only a limited amount of information at a time.

Other parts of our brain, however, that operate below the level of conscious attention, are able to dedicate a lot more resources to processing these tasks: even though we don’t always realize this is going on.

I suspect this is what was happening during my paper review. While reading the paper, my conscious mind could only hold a limited amount of the complex information in my working memory at any given moment. The result was the frustrating feeling that I didn’t understand how the pieces fit together.

In the background, however, other parts of my brain were processing this information, trying different configurations and looking for effective ways to fit things together into a more coherent assembly.

When I then tasked myself with summarizing what I knew, my conscious brain tapped into this large reservoir of unconscious work, surprising me by how much I actually understood.

At least, this is one possible explanation.

Process then Summarize

Regardless of the exact source of the phenomenon I encountered, I suspect the strategy that generated it provides a useful deep habit for many cases where you must make sense of a large amount of complicated information.

Spend time to process the information, piece by piece, with full concentration. Once you’re done, step back and try to summarize what you learned. Though the process of digesting the information might feel frustratingly scattered, you’ll likely be surprised by how much work the other parts of your mind accomplished on your behalf. By writing down what you know, you cement this effort.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers