Thomas Aquinas’ Argument From Finality of Being: A Socratic Dialogue

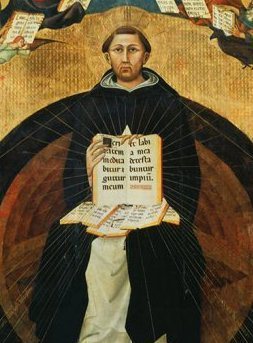

St. Thomas Aquinas

In this conversation, Brad and Sarah discuss St. Thomas Aquinas’ fifth proof for the existence of God, the argument from finality. You can read their conversation about Aquinas’ first two proofs here, their conversation about his third way here, and their conversation about his fourth way here.

Brad: Okay, I’ve actually read the fifth way. Looked it up online last night. I have it here. He writes:

“The fifth way is taken from the governance of the world.

We see that things which lack intelligence, such as natural bodies, act for an end, and this is evident from their acting always, or nearly always, in the same way, so as to obtain the best result.

Hence it is plain that not fortuitously, but designedly, do they achieve their end. Now whatever lacks intelligence cannot move towards an end, unless it be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence; as the arrow is shot to its mark by the archer.

Therefore some intelligent being exists by whom all natural things are directed to their end; and this being we call God.”

Sarah: How would you summarize that?

Brad: Okay, I’d say that everything we see acts as if it has an end. Seeds grow into flowers, not chickens; puppies become dogs, not Beethoven. Thomas wants to say that the only explanation for this is that there is a God directing it all.

Doesn’t The Theory of Evolution Destroy This Argument?

Brad: But surely evolution has done away with this argument which may have sounded plausible in the 13th century when Aquinas lived.

Sarah: Actually it’s only strengthened it. Aquinas isn’t saying that really complex beings need an explanation for why they are so complex (evolution explains that). He wants to know why unintelligent causes move towards intelligible ends. Even a simple electron orbiting an atom would prompt the question, why does it do this when there is an infinite number of ways it could act unintelligibly?

Brad: What do you mean by unintelligent causes? Causes that are unguided?

Sarah: Causes that do not have a principle within them to achieve their goal. When an arrow hits a target it does so through an intelligent agent guiding it. The same is true for other regular natural processes. Saying that “laws of nature” answer this only pushes the problem back one step.

Brad: Are you saying that if God didn’t exist a seed might become a box of cheerios? and another a candle?

Sarah: Im asking what would we expect the world to be like if there was no God. If something could exist without God—which I don’t believe is possible but will grant for the sake of argument—is it more likely to be disordered or ordered? There’s a great line from Anna Karinina, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The same for universes, ordered universes are rare and all alike, disordered ones are infinitely more common.

Is Order An Illusion

Brad: Our minds create order, we impose it upon the universe. I think that’s what I’d like to say. In a similar way to how we might hear a tune or beat out of the random tumblings of a clothes drier.

Sarah: I think by “impose” you mean “recognize”. If by chance a dryer makes a repetitive pattern we recognize it. But if it pumps out Lady gaga we might suspect an intelligent agent is at work. Do you think that our minds are what cause the planets to unfailingly orbit the sun?

Brad: No, obviously not. But I think we are wired to detect order and meaning even when those things aren’t there. For example, kids typically think that mountains exist so that creatures can have a place to live. As they grow older they’ll hopefully recognize that mountains are the result of a great amount of melted rock pushing its way up under the earth . . . in other words, hopefully they’ll grow out such simplistic explanations. Saying, “planets keep going around the sun, WOW! God must exist!” seems to me just as naive.

Sarah: I agree that the explanation children give for mountains is backwards, people make mountains a place to live rather than discover the mountain was made for them but that won’t work for all explanations. Don’t you ever wonder why natural processes always and unfailingly lead to intelligent ends. Unintelligent gravitons lead to planets that always orbit, unintelligent pieces of rock and pressure lead to mountain ranges that always form. If the universe is an accident, why is this accident so regular?

Brad: I don’t know. But if I were to conclude from my not knowing, “God must exist” that would be a textbook example of the god-of-the-gaps fallacy, where you fill in what you don’t understand about the universe with, “it must be God.”

Sarah: That’s not how Aquinas argues. He uses other examples of intelligent ends involving unintelligent causes and then demonstrates how all ends we observe must have an intelligent cause at some point in their development. But to understand that you have to understand the metaphysics that underlies the argument. Let me give you an example, I assume you believe in evolution, right?

Brad: I think it is a fact, yes.

Sarah: Alright, well suppose someone said that evolution doesn’t make sense because they just can’t see how a pool chemicals can give rise to humans through chance and time. They say that we wouldn’t say an airliner came about through chance + time, so why think life did the same thing. You’d probably say they don’t understand how evolution works and that it’s not a simplistic chance + time scenario. You might even recommend some writers on the subject like Richard Dawkins or Jerry Coyne that breakdown the complex parts of the theory in order to explain the whole thing. Right?

Brad: Indeed! I’m relieved to hear that you’re not going to try a similar analogy.

Further Reading

Sarah: Well, I’d like to offer you something similar. First, Aquinas’s Five Ways aren’t full fledged proofs for God. If they were, it would be strange that Thomas only spends two pages out of the 3500 in the Summa defending it. The reason for this is that they are intended to be summary for novices. However, other philosophers have explained the metaphysical claims of the argument and defended them from common objections. They help us understand what Thomas means by terms like “act”, “potency” and “cause” the latter of which is crucial for understanding the fifth way. Perhaps you’d like to read them? One I recommend is Edward Feser’s Aquinas a A Beginner’s Guide. If you’re hesitant, just remember that attitude you’d like a creationist to have if they read something Dawkins wrote on why evolution is true. Then perhaps we can have an in-depth discussion after that.

Is The Best You Got?

Brad: Here’s an honest question, and then I gotta get going. I’m disappointed that none of these arguments—even when taken together—aren’t very convincing. If I were you, I’d be bothered that here you are hanging so much importance on God existing and these are the arguments you use. Can you not see how people like myself remain unconvinced?

Sarah: The reason these arguments may seem unconvincing is because we as moderns have assumed a certain view of the universe that might not be true, that it’s just a blind, atomistic machine.

But these arguments encourage me to ask deep questions like “Why is there change?” “Why is there regularity?” “Why is there something rather than nothing?” And they encourage me to not stop until I get to a final explanation, and not just a God of the gaps one.

It seems to me that you just want a miracle and that’s all you’ll accept as proof that God exists. But just as we allow a painting itself to prove it was composed without expecting the artist to come to our door to tell us, shouldn’t we allow the universe to do the same? Of course you’ll say “paintings aren’t like universes!” and that’s true to some extent. But the more we explore the world, it’s causes and underlying metaphysical truths, we see they really aren’t that different.

That’s why I encourage you to read up more on these arguments and being open to the evidence, and not just shutting down ultimate questions of existence with “science will figure it out some day.”

Brad: It’s been good chatting with you, Sarah.

Matt Fradd's Blog

- Matt Fradd's profile

- 168 followers