Relics – We Are and We Are Not Perfect

The Relics series are throwback articles from previous years. They seem timeless enough to be relevant today.

The Relics series are throwback articles from previous years. They seem timeless enough to be relevant today.Try as you will, you cannot annihilate that eternal relic of the human heart, love. – Victor Hugo We Are and We Are Not Perfect

(Note: I did do a major overhaul on this piece, so if you read it last year, give it a once over)

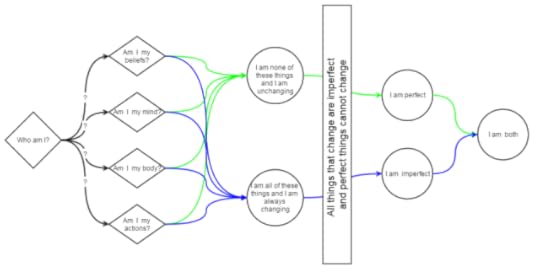

This is the second in a series of concept diagrams I’ve fiddled with to work through some traditionally complex Buddhist ideas. The diagram plays with the notion of the Great Perfection or Two in One as my teacher explained it to me.

It’s a paradox of sorts. At the base of it is the existential riddle of Who am I? I chose a visualization to avoid the confusion that comes with holding two contrary ideas in your mind at the same time.

click to enlarge

Two In OneWho am I? What is the self? This is where we have to be honest. We have to be scientific. We can only go as far as the data allows us to. No more, no less.

How do we answer existential questions? Humans have been stumbling on them for millennia. So don’t get down if you’re confused. Most of the time, I’m confused. Let’s try to get at the self by asking a few questions about it and exploring the possible answers.

Am I My Beliefs?When we think about others, we see them as a constellation of qualities. Beliefs are an important one. We see some friends as religious, others not so much. Many have political convictions. Some friends like old Star Trek, others like Next Generation, and others just don’t care. We choose our companions in part based on their beliefs.

So when we think about self, we do think in terms of beliefs. But we also have to concede, we are not solely our beliefs. There is certainly more to us than that.

Am I My Mind?There is a lot to the notion that everything is mind. Eastern and western philosophical traditions have both converged on the understanding that we see the world through the filter of our mind. Language, symbols, and logic are the ways that the mind creates a working map of the real world. We operate primarily in this domain, rarely getting out of our heads to come in contact with “reality”

But despite the important role the mind plays in who we are, we are not mind alone. For example….

Am I My Body?The body includes the brain. The brain functions as the substrate for the mind. Wouldn’t it make sense then to assume that we are our bodies?

But wait, a few challenging questions show us that isn’t true either. If we were to lose a finger or a toe, are we no longer me. All the cells in the body are entirely replaced every 2500 or so days. Do we become a different person?

Proximately we are our bodies, but ultimately we are not.

Am I My Actions?Aristotle is quoted as saying, “We are what we repeatedly do.” This is true in many ways. We are judged by our behavior; accepted or rejected by the quality of our actions.

But again there is ambiguity. Our actions are important, but to propose that there is nothing else ignores our inner dialogue and intentions. Our actions do not fully encapsulate who we ultimately are.

Definitely Sort OfThe answers to these questions are yes,.. and no. Is that a problem? Let’s think about it.

In science, often time the key to a new discovery lies in framing the question right. If we have questions that have ambiguous answers, then perhaps we haven’t formulated the hypothesis well.

Imagine the birth of ornothology (the study of birds). An early bird watcher proposes classifying birds by their color patterns. He proposes that all birds can be divided into two classes; solid color birds and speckled birds. A robin would be a solid color class of bird and a European starling would a speckled class bird. It appears we can continue on with our classification for all birds. But alas, along comes a long billed thrasher. In this case, the bird is both solid colored and speckled. Is this impossible? No, it’s just the way it is.

Do I go into existential angst because I no longer know what birds are? I hope not.

The same applies to the self. In a relative sense, we are all this or that. We’re Democrats, blondes, engineers, and Buddhists. But these things don’t describe us fully in the absolute sense. This is the paradox of the Great Perfection.

So there appears to be two ways to look at who we are. First we can see ourselves as an aggregation of a great number of qualities. We can see ourselves as aggregates of our beliefs, experiences, physical attributes, and actions. We also have to acknowledge that these aggregations are always changing.

But we also know that all of these things seem to fall short of answering the question of who we really are. Here’s a place where it gets sketchy. Even Buddhists will disagree on this, because it lies at the crux of the chief philosophical problem that humans have been struggling with for millennia. That is, if I’m not just the sum of all of my parts, then what completes the puzzle?

I’m going to place the problem on a continuum. This helps me avoid what are described as extremes in Buddhism. The aggregates I spoke of earlier (body, mind, actions, etc) lie on the left hand side of this continuum. These things are relative, temporary, and always changing. On the opposite end of this spectrum lies the absolute, permanent, unchanging, and thus perfect. I equate perfect with unchanging for the following reason. If something changed, then, of course, it would either get better or worse. Therefore, if something changes, it cannot be perfect. The inverse would also be true. If something is perfect it cannot change. The best example of something that fits this description is the Abrahamic God.

click to enlarge

So If we take the question of who we are on this continuum, where would we lie? We are not the sum of our parts and we certainly don’t act like we’re all knowing, all powerful, perfectly good gods. So what gives?

Perhaps both things are true in that we lie somewhere in the middle.

So when we look to understand self, we might see ourselves as a little bit of both. A little bit county and a little bit rock ‘n’ roll. We are simultaneously ever changing imperfect beings and perfect unchanging beings. We are frail, troubled and broken individuals. But, we are also the universe looking back on itself, perfect in its completeness. We are two in one.

Get Each Week's Relics article in your email boxFirst Name:

Last Name:

Email address:

Select a Weekly Series You'd Like to Follow:

One Minute Meditations

Tiny Drops (Photography series)

Compass Songs (My Favorite Poems)

Dialectic Two-Step

Modern Koans (interesting questions)

Sunday Morning Coming Down (Music Videos)

Relics (Timeless Republished Articles)

The post Relics – We Are and We Are Not Perfect appeared on Andrew Furst.