Excerpt from Unveiling the Mystic Ciphers

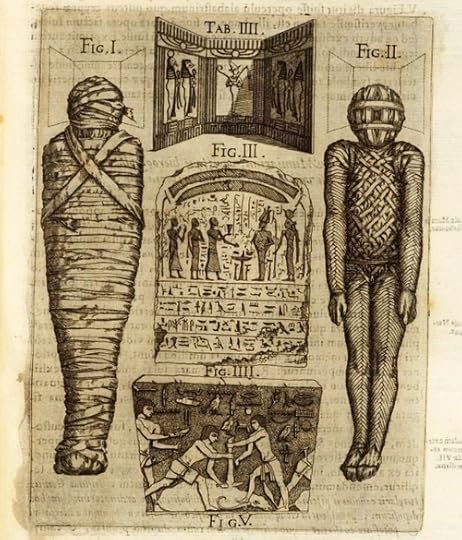

Egyptian funerary practices, from Athanasius Kircher’s Oedipus Aegyptachus.

In 1967 David Kahn wrote the first exhaustive history of cryptography, beginning with its earliest appearance thousands of years ago in Egypt and following its progress throughout history until modern times. In his examination of early cryptography, Kahn pointed out that the first recorded form of encryption was found in hieroglyphics on Egyptian tombs. The Egyptians were the first known authors to actively try to transform the writing from a basic sign, whose meaning was easily translated, into a more complex sign whose translation required more involvement on the part of the reader.

Why? Because this transformation added a second level of meaning to the text. The first was the standard, or plaintext meaning of the language. The second, deeper significance was the effect gained by using some means to alter the presentation of the text to the reader. A simpler, more straightforward symbol or word could have been used, but the author chose a more unique symbol to add a greater sense of dignity to the tomb, or to catch the eye of more readers. Eventually this led to what modern culture might see as word-games, which both challenged the reader and entertained them at the same time. Kahn states:

As Egyptian civilization waxed…these transformations grew more complicated, more contrived and more common…

…But many inscriptions are tinctured, for the first time, with the second essential for cryptology –secrecy. In a few cases, the secrecy was intended to increase the mystery, and hence the arcane magical powers of certain religious texts. But the secrecy in many more cases resulted from the understandable desire of the Egyptians to have passersby read their epitaphs and so confer upon the departed the blessings written therein…They introduced the cryptographic signs to catch the reader’s eye, make him wonder, and tempt him into unriddling them –and so into reading the blessings. [1]

From cryptography’s inception in antiquity through its development over time; from the middle-ages to the renaissance and the modern era, it has been inextricably connected to the intertwined worlds of religion, science and the occult. Language contains an elemental power. Secret language exponentially expands the perception of that power. It is no accident that the publications of many of the greatest innovators in cryptography, such as Johannes Trithemius and Blaise de Vigenère, often delve just as deeply into esoteric studies of religion, alchemy and occult knowledge as they do into the art of encryption. Perhaps this is the reason why the mystery of secret writing, whether on an ancient tomb or in a Sherlock Holmes novel, creates an intoxicating lure for the curious mind.

In the modern era this connection has lessened somewhat, especially as technology has accelerated the capabilities and prevalence of cryptography in every aspect of daily life. Specialists in the area are now mathematicians and engineers, not historians, clerics and alchemists. The mystery has faded. The mixtures of disciplines have separated. Now they present themselves as independent fields of study, neatly arranged on different pages of our college course catalogs. Some have disappeared altogether. And cryptography is now a commodity to be purchased on the common market and deployed by the masses, with little or no understanding of its functional workings or the context of its development.

Much of the early fascination of cryptographic mysteries is gone, but some esoteric puzzles still remain. The Shepherd’s Monument is one of them. It crosses the timeline of cryptographic history at that point just as the magic was fading, as science began to ascend to the throne of knowledge and divorce itself from other less tangible fields. Here, an English gentleman at the crossroads of the Rosicrucian Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution set in stone a marble picture and ten cryptic letters. At this unique moment in time, Thomas Anson built a monument which holds a secret. A Shepherdess’s Tomb whose inscription, like those Egyptian tombs thousands of years before it, begs us to spend some time working out its ciphers. They catch our eye, make us wonder, and tempt us into unriddling them –and so perhaps, into reading their blessings.

[1] Kahn, David. The Code Breakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet, (New York: Scribner, 1996), 71-72.