Only God Could Have Created Christopher Hitchens

There is but one man who could have lured me away from my husband. Even if just for a tawdry weekend of boozing, arguments, smoke-filled hotel rooms and failed attempts at consummating some form of lust.

There is but one man who could have lured me away from my husband. Even if just for a tawdry weekend of boozing, arguments, smoke-filled hotel rooms and failed attempts at consummating some form of lust.

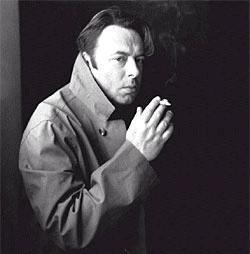

That man was Christopher Hitchens.

Hitch has been dead for four years and I still miss him. It wasn’t an anniversary of his birth or death that made me get all *sniff* about him once again, it was picking up a copy of Vanity Fair at the gym.

Having not glanced through the magazine in at least a couple of years, I’d forgotten how little it has to offer now that Hitch is gone from its pages. Without him, Vanity Fair just depresses me. It’s an empty Prada suit. An actor trying desperately to sound smart.

For those of you who are a little fuzzy about who Christopher Hitchens was, I’ll tell you a bit about him, then go on to tell you what he meant to me. To Wikipedia, he was “a British-American author, philosopher, polemicist, debater, and journalist. He contributed to New Statesman, The Nation, The Atlantic, The London Review of Books, The Times Literary Supplement and Vanity Fair.”

To me, he was a contrarian, a true thinker, a heart-felt belly laugh, and bright spot in so many dreary days.

���The four most over-rated things in life are champagne, lobster, anal sex and picnics,��� he observed rightly.

Unlike other public intellectuals, who are most often pompous prigs who make you want to run for your life, Hitch was a good time. He looked like hell, drank as spiritedly as he argued, told great jokes and judged his fellow man only by merit and character. His friends said he made hipsters look needy.

Of course, his hard living killed him in the end, but even about that, he was unrepentant.

“In one way, I suppose, I have been ‘in denial’ for some time, knowingly burning the candle at both ends and finding that it often gives a lovely light,” he said, after being diagnosed with esophageal cancer in 2010.

He told Charlie Rose in a subsequent television interview, ���Writing is what���s important to me, and anything that helps me do that ��� or enhances and prolongs and deepens and sometimes intensifies argument and conversation ��� is worth it to me,��� adding that it was ���impossible for me to imagine having my life without going to those parties, without having those late nights, without that second bottle.���

I realize a lot of people didn’t like Hitch and weren’t sorry to see him go – maybe not from life itself, but certainly from the public stage. The fact is, the man was contentious, self-important and never afraid to change his mind.

A passionate Marxist in his youth, he broke ranks with the Left for the first time when his dear friend, Booker Prize Winner Salman Rushdie, began receiving death threats after the publication of his novel, “The Satanic Verses,” in 1989. The book apparently offended certain Muslim clerics, including none other than the Ayatollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran at the time. He sentenced Rushdie to death with a “fatwa,” and forced him into hiding.

The glitterati, Hitchens felt, were mealy-mouthed in support of their colleague.

“Utterly spineless,” Hitchens would say.

For all of their posturing about human rights, when it came time for the Left to stand by their friend, Rushdie, they did not. Hitchens never forgave them.

���It was, if I can phrase it like this, a matter of everything I hated versus everything I loved,��� he wrote in his memoir, “Hitch-22.” ���In the hate column: dictatorship, religion, stupidity, demagogy, censorship, bullying and intimidation. In the love column: literature, irony, humor, the individual and the defense of free expression.���

But his hatred of Henry Kissinger, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan kept him on the up and up with his friends at “The Nation,” even if they had to hold their noses after he publicly excoriated them for their cowardice on the Rushdie issue.

It wouldn’t be until the September 11th attacks in 2001 that Hitchens would sever his ties with “The Nation,” and thus effectively the Left, for good. His enthusiastic and unwavering support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan was an unforgivable breach. Especially since – right or wrong – he could argue his conclusions better than anyone on either side of the debate.

But if you think he went running into the arms of the Right, think again. While hawkish in his desire to “fully destroy our enemies. I hate them. With a passion,” he said. He was no friend of the Right. He despised religious fundamentalism and frankly, religion, on any level, and found the Right’s Civil Rights and Women’s Rights legacy appalling. While he wrote an eloquent piece in “Slate” about why he did not regret George W. Bush’s two turns in the White House, he supported Obama in 2008.

“I don’t envy or much respect people who are completely politicised,” he said.

To the frustration of both his friends and enemies, Hitch switched sides with a kind of ruthlessness that indicated his attachment to thought not ideas. And that’s what I loved so much about him. He understood how crippled one was without the other. How ideas – no matter how great and important – are meant to be assailed by thought and assailed mercilessly. Ideas on politics, on sexuality, on science, on class, on race, and yes, on religion.

“I learned that very often the most intolerant and narrow-minded people are the ones who congratulate themselves on their tolerance and open-mindedness.”

Ain’t that the truth.