Why The Owl Service isn’t as easy as a computer thinks it is.

My friend and fellow children's writer Cecilia Busby commented in a recent blog post for the 'Awfully Big Blog Adventure' on a computer-run reading scheme used in schools, Accelerated Reader. Developed as a guide for teachers and parents, the scheme assesses and grades books for young readers. It awards each title a number on a scale ranging from easy (around 3) to difficult (11 or 12), and encourages children to read by awarding collectable points for each title and providing quizzes to test their understanding. The scheme is popular and widely used, but Cecilia discovered some anomalies in its grading system. For example, Accelerated Reader grades Alan Garner’s 1967 book The Owl Serviceas easier for young readers than his debut novel The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Anyone who’s actually read the books will know that this is bonkers. Intrigued, I took a closer look to try to find out how such a mistake could have been made.

My battered, much-loved childhood copy

My battered, much-loved childhood copyIt seems the AR programme judges books by length, complexity of syntax and difficulty of vocabulary – including proper nouns. Although The Owl Service contains a number of unusual Welsh names such as Lleu Llaw Gyffes and Gronw, it can’t compare with The Weirdstone of Brisingamen’s whole bunch of unusual polysyllabic names such as Durathror, Fenodyree, Angharad, Llyn-dhu, Fundindelve, Cadellin, Atlendor, and of course the eponymous Weirdstone itself. Moreover, a glance at any page of The Owl Service will show a high proportion of dialogue – and consequently shorter, snappier sentences and simpler syntax – than the many long narrative paragraphs of The Weirdstone. So the dutiful AR computer has awarded The Owl Servicea lowish 3.7 and banded it MY (Middle Years) for children aged 9-13, while The Weirdstone has been pushed right up to 6.3 and banded UY (Upper Years) for readers of 14 and over.

The Owl Service is far more advanced, difficult and sophisticated book than The Weirdstone, but the computer does not know this, because it literally cannot read between the lines. All the most interesting stuff in The Owl Service goes on in the spaces and silences and misunderstandings between the characters. And that’s the trouble. Reading isn’t just about understanding what words say. It’s also about understanding what they imply.

Here is the elliptically brilliant opening page of The Owl Service:

‘How’s the bellyache, then?’ Gwyn stuck his head round the door. Alison sat in the iron bed with brass knobs. Porcelain columns showed the Infant Bacchus and there was a lump of slate under one leg because the floor dipped. ‘A bore,’ said Alison. ‘And I’m too hot.’ ‘Tough,’ said Gwyn. ‘I couldn’t find any books, so I’ve brought one I had from school. I’m supposed to be reading it for Literature, but you’re welcome: it looks deadly.’ ‘Thanks anyway,’ said Alison. ‘Roger’s gone for a swim. You wanting company, are you?’ ‘Don’t put yourself out for me,’ said Alison. ‘Right,’ said Gwyn. ‘Cheerio.’ He rode sideways down the banisters on his arms to the first floor landing. ‘Gwyn!’ ‘Yes? What’s the matter? You OK?’ ‘Quick!’ ‘What’s the matter? You going to throw up, are you?’ ‘Gwyn!’He ran back. Alison was kneeling on the bed.‘Listen,’ she said. ‘Can you hear that?’‘That what?’‘That noise in the ceiling. Listen.’The house was quiet. Mostyn Lewis-Jones was calling after the sheep on the mountain: and something was scratching in the ceiling above the bed.

This apparently effortless piece of text provides immense density of information: but it takes time to unpack. We learn – if we are really thinking while we read – that the scene is set in a bedroom on the top floor of an old Welsh house (the uneven floor and the old brass bed); we learn that the weather is hot, probably summer; we learn that the house is situated among mountains where sheep are reared. We are introduced to three main characters by name, and we see that while the unseen Roger has gone swimming, Gwyn is interested in Alison. He brings her a book and asks how her tummy-ache is (perhaps she has period pain; they must be teenagers) and, pseudo-casually, asks if she wants his company. When she reacts ungraciously, he pretends not to care – only to speed back upstairs to her side as soon as she calls him, to listen to something scratching up in the ceiling.

No inexperienced reader is going to ‘get’ all this – or any of it – or be especially interested if they did. Imagine a younger child deciphering ‘what happens on the first page’ without understanding the subtext. ‘A girl is sick in bed. I don’t know what all the stuff about porcelain columns and Bacchus is supposed to mean. A boy brings the girl a book which he says is boring. They talk a bit. Then he goes downstairs and then she calls for him and he thinks she’s going to be sick, and then she tells him to listen to a scratching noise.’ On the surface, little is happening. It could seem disjointed, confusing, dull.

Like the very grown-up tale from the Mabinogion which inspired it, The Owl Service is about nothing if it is not about relationships, and Garner expects the reader to work at the implications of his prose. He rarely tells us what anyone thinks or feels, or what they look like. But it’s all there.

Compare the much more conventional first page of The Weirdstone (not counting the prologue, The Legend of Alderley):

The guard knocked on the door of the compartment as he went past. “Wilmslow fifteen minutes!” “Thankyou!” shouted Colin. Susan began to clear away the debris of the journey – apple cores, orange peel, food wrappings, magazines, while Colin pulled down their luggage from the rack. And within three minutes they were both poised on the edge of their seats, case in hand and mackintosh over one arm, caught, like every traveller before or since, in that limbo of journey’s end, when there is nothing to do and no time to relax. Those last miles were the longest of all. The platform of Wilmslow station was thick with people and more spilled off the train, but Colin and Susan had no difficulty in recognising Gowther Mossock among those waiting. As the tide of passengers broke round him and surged through the gates, leaving the children lonely at the far end of the platform, he waved his hand and came striding towards them. He was an oak of a man: not over tall, but solid as a crag, and barrelled with flesh, bone and muscle. His face was round and polished; blue eyes crinkled to the humour of his mouth. A tweed jacked strained across his back, and his legs, curved like the timbers of an old house, were clad in breeches, which tucked into thick woollen stockings just above the swelling calves. A felt hat, old and formless, was on his head, and hob-nailed boots struck sparks from the platform as he walked.

Fifty-five years after it was written, these long sentences might strike a modern child as a bit slow, but they present few challenges and there is a reassuring sense of direction: when they get off the train, very soon, an adventure will begin. True, the train isn’t quite like a modern train, and children might not now (did they ever?) divide tasks quite so readily into ‘girl clears up the litter and boy lifts down the cases’ – and ‘limbo’ and ‘mackintosh’ might conceivably puzzle some young readers. Still, the first half-page is a straightforward narrative, while the second half is an equally easy-to-follow description of Gowther Mossock – perhaps a little lengthy, but Gowther’s solid dependability renders him an important emotional anchor in the adventures that lie ahead. For The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is of course not about relationships. Though there are few signs of it in that conventional opening, the book is a fiery, frosty fantasy which burst upon my twelve year-old consciousness like a firework of marvels, magic and excitement. In those days even children expected a book to start in a leisurely manner and to gather momentum as it went along, but it is still a far more accessible story for a young reader than The Owl Service can ever be.

For a writer to progress from The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to The Owl Service in seven short years (1960 – 1967) was to display extraordinary talent. Alan Garner is one of our greatest living writers. But I need to confess in this context, that as a young reader, I couldn’t keep up. And I was a really good reader, a child who read all day, every day. I devoured at least ten books a week. I was probably ten or eleven when I first read The Weirdstone, and over the next few years I read it and its sequel The Moon of Gomrath (1963), and Garner’s third children’s book Elidor (1965) multiple times, and secretly began writing Garner-inspired fiction of my own. But I wasn’t progressing as a reader at the same speed that Alan Garner was progressing as a writer. He was accelerating away from me, and with Red Shift in 1973 seemed in fact blue-shifting from children’s into adult fiction. When I first read The Owl Service at the age of 13 or so I found it dry and spare and difficult. I looked in vain for the colour and richness of the earlier books, and its pared-down dialogue was wasted on me. If The Owl Service had been the first book I’d read by Alan Garner, I doubt if I would ever have tried his others. And that would have been a great shame.

But the computer goes by rule-of-thumb. The computer looks at syntax and vocabulary. The computer thinks The Owl Service is for children of 9 to 13 and The Weirdstone of Brisingamen is for teenagers of 14 plus. I’m not mocking. Friends assure me that the AR programme really does encourage schoolchildren to read, that many of them like the element of competition and enjoy amassing points for the titles they read. So long as they are also enjoying the books themselves, that’s good. But parents and teachers should know that the system isn’t foolproof. The computer which assesses and grades these titles cannot actually read – in a human sense – at all.

A computer can never replace an experienced librarian.

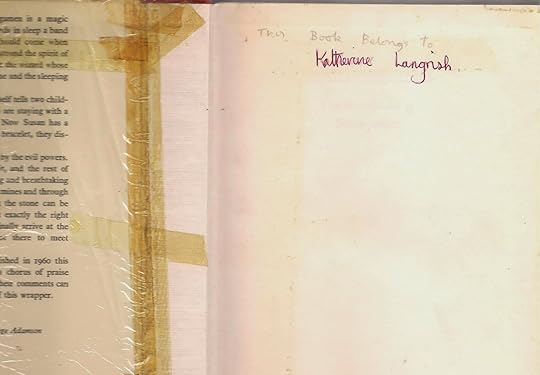

Stuck together with Sellotape, my 1965 edition of The Weirdstone with my name written inside

Stuck together with Sellotape, my 1965 edition of The Weirdstone with my name written inside

Published on January 12, 2015 04:10

No comments have been added yet.