Nous Sommes Charlie, But Do We Really Want To Be?

Don’t tell me Charlie Hebdo wasn’t racist because it attacks all religions… Then what is this? pic.twitter.com/0wPCAjcPrd

— #InCarloWeTrust ⭐️ (@UnbelievaBALE) January 8, 2015

Radical proposition: one can despise violence against #CharlieHebdo w/o signing off on their racist bullshit.

— Sean Lee (@humanprovince) January 7, 2015

Yglesias, for one, is dismayed that yesterday’s attack made martyrs of cartoonists whose work he found distasteful in the extreme:

Viewed in a vacuum, the Charlie Hebdo cartoons (or the Danish ones that preceded it) are hardly worthy of a stirring defense. They offer few ideas of value, contribute little to any important debates, and the world would likely have been a better place had everyone just been more polite in the first place.

But in the context of a world where publishers of cartoons mocking Mohammed have been threatened, harassed, and even killed, things look different. Images that were once not much more than shock for its own sake now stand for something — for the legal right to blaspheme and to give offense. Unforgivable acts of slaughter imbue merely rude acts of publication with a glittering nobility.

One of Dreher’s readers makes a similar point:

I am a francophone European, and I sometimes read Charlie Hebdo. I am shocked by these murders and I hope the assassins will be caught and will pay dearly for their crimes. This being said, je ne “suis” pas Charlie et je ne l’ai jamais été: I am not Charlie and I never was.

I’ve always thought that Charlie’s brand of “humour” was despicable and part of the problem, not a solution. I’m not going to change my mind about this because of the murders. The people who died have become martyrs of the freedom of expression, but they were hardly the best defenders of the freedom of expression. First because the freedom to express your opinions does not imply that these opinions are correct – and Charlie was a far left, violently anti-religious rag. It is not because you are free to be vulgar, unfair and insulting that all these things are good. Moreover Charlie was not very good when the freedom of expression of its adversaries was at stake: look at the “Dieudonné” affair for instance.

Dieudonné M’bala M’bala is a controversial French comedian and political activist who’s been convicted many times of antisemitism. Diana Johnstone is on the same page as Dreher’s reader when it comes to Charlie Hebdo‘s spotty record on free speech:

In 2002, Philippe Val, who was editor in chief at the time, denounced Noam Chomsky for anti-Americanism and excessive criticism of Israel and of mainstream media. In 2008, another of Charlie Hebdo’s famous cartoonists, Siné, wrote a short note citing a news item that President Sarkozy’s son Jean was going to convert to Judaism to marry the heiress of a prosperous appliance chain. Siné added the comment, “He’ll go far, this lad.” For that, Siné was fired by Philippe Val on grounds of “anti-Semitism”. Siné promptly founded a rival paper which stole a number of Charlie Hebdo readers, revolted by CH’s double standards. In short, Charlie Hebdo was an extreme example of what is wrong with the “politically correct” line of the current French left.

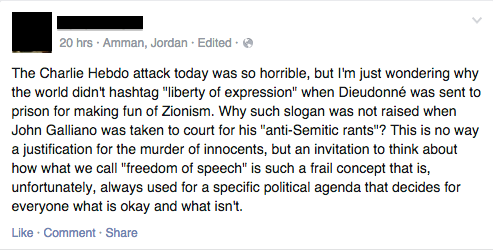

Indeed, many Muslims on social media are wondering why free speech seems a bit freer than usual when Islam is the target. One such Muslim is a Jordanian friend of Dish editor Jonah Shepp, who didn’t want to reveal her name:

Meanwhile, responding to calls for other publications to reprint Charlie’s most controversial work in solidarity, Arthur Goldhammer cautions against sacralizing artists and journalists who saw profaning the sacred as their life’s work:

Reproducing the imagery created by the murdered artists tends to sacralize them as embodiments of some abstract ideal of free speech. But many of the publications that today honor the dead as martyrs would yesterday have rejected their work as tasteless and obscene, as indeed it often was. The whole point of Charlie’s satire was to be tasteless and obscene, to respect no proprieties, to make its point by being untameable and incorrigible and therefore unpublishable anywhere else. The speech it exemplified was not free to express itself anywhere but in its pages. Its spirit was insurrectionist and anti-idealist, and its creators would be dumbfounded to find themselves memorialized as exemplars of a freedom that they always insisted was perpetually in danger and in need of a defense that only offensiveness could provide.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers