Putting things in order at the British Library

By DAVID HORSPOOL

Sometimes, dating things can be a bit of a distraction for historians, though putting things in the right order might seem like the least we should expect of them. Yesterday, at the British Library’s announcement of their exhibitions and events for 2015, dates were much discussed. There were anniversaries: 800 years since Magna Carta, 150 since the publication of Alice in Wonderland, 200 since the birth of Anthony Trollope.

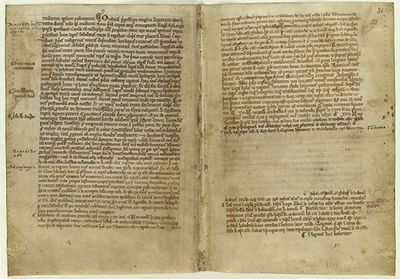

But there was also the question of putting things in order. For the Library’s Magna Carta exhibition, “Law, Liberty, Legacy”, which will run from March 13 to the beginning of September next year, one of the most intriguing exhibits will be the Library’s manuscript of the Scottish Melrose Chronicle, Cotton MS Faustina B IX (pictured above), which contains what is described as “the earliest independent account of the negotiations between King John and the Barons at Runnymede”.

While the revelation of this may be exaggerated (the modern printed edition of the Chronicle of Melrose was published in the 1930s, for example), it is arguable that historians have been looking the wrong way, seduced by the help that the Scottish account can give in ordering the confused events of June and July 1215, when a group of English barons and senior churchmen tried to tie King John to some formal obligations, and John did his best to wriggle out from under them. So in J. C. Holt’s classic account of Magna Carta, Melrose is introduced mainly to provide evidence of whether what we know as Magna Carta was sealed at Runnymede in June, or in Oxford in July (and in fact, the chronicler doesn’t mention Runnymede). Holt describes Melrose as a “somewhat confused narrative”but uses it to help him confirm that Runnymede is where the document was sealed, and Oxford where John repudiated it.

But the remarkable fact that the impact of the events of 1215 had, so soon after they happened, spread as far as Melrose, and that the monk who recorded them was moved to do so in Latin verse, is passed over without comment. It used to be a truism of Magna Carta historiography that the Charter at the time was a narrow self-serving document that made little impact. That is the tenor of another exhibit, a letter written from the Colonial Office in 1947 refusing to endorse a “Magna Carta Day” in the Commonwealth, not only because it might give “ill-disposed colonial politicians” the wrong idea, but because Magna Carta itself is deemed to have little to do with wider questions of rights and responsibilities. The Melrose Chronicle, with its description of the barons’ attempt to get the King to “make a thorough reform of the laws”, creating “a new state of things in England . . . for the body wishes to rule the head, and the people desired to be masters over the king”, shows that soon after Magna Carta was drawn up, its wider implications were already hitting home.

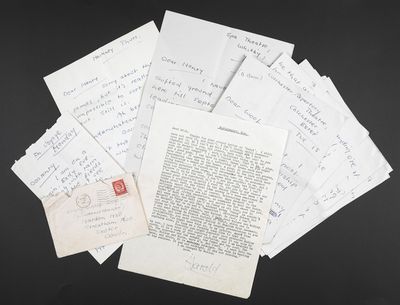

Dating crops up again in the case of a collection of early letters of Harold Pinter (pictured below), the acquisition of which was also announced yesterday. There are about 100 of them, written to childhood friends (Mick Goldstein and Henry Woolf) when Pinter was between eighteen and thirty. Many have no dates. But the Library was able to pin down about a third of them by making use of Pinter’s constant cricket references. So, for example, in a letter to Goldstein of 1955, discussing Beckett,and insisting that his friend sees “En Attendant Godot” at “the Arts in London (“Are you going to do this?”; Pinter had not himself seen the play), it is the reference to “Padgett” (“you brought his stroke to me, and lo, didn’t he get a century yesterday, to bear out your words”) that helps the curators to say that the letter “must have been August 1955”.

Actually, this merits further investigation, or perhaps explanation, as Doug Padgett only scored one first class century in 1955, for Yorkshire against Warwickshire at Edgbaston, where on the first day he was bowled for 115. That was July 23, which, if it was Pinter’s “yesterday”, may mean the letter was written on July 24. But I could be wrong, and though dates do matter, it is perhaps more important to note that the young Pinter was clearly enthralled by Beckett, even if he was yet to see Godot.

It is also interesting that Pinter writes about “Betty”, described by a third party as “secretary to some Irish writer she’s been translating his work from French back into English [sic]”. Pinter says he met Betty, but doesn’t give her last name. Pinterians and Beckettians probably know all about her, but I was intrigued to learn of this woman who apparently translated Godot and Molloy back into English, a task I had always thought Beckett completed on his own. Pinter writes that Betty “spoke a lot of ‘En Attendant Godot’ and is going to send me a copy, I hope. In French, though. Once again all I got was that two tramps sat and talked, waiting . . .”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers