Some like it Scot? It’s in the dress!

Some Like it Scot! Scottish that is. What draws us to the Man in Highland Dress?

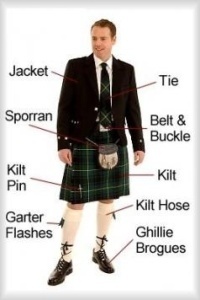

Do you hear music while gazing upon that picture?? Okay, well that is more like Highland undress, but I’m good with it. Really, let’s have a little lesson on the Highland dress:

Highland dress is one of the most distinctive and attractive national costumes in the world and has survived the passing of centuries with consummate ease. The basic elements of Highland dress – the kilt and the sporran – have changed very little in 300 plus years and are just as likely to be seen today on New York’s Fifth Avenue as they are on Edinburgh’s Princess Street.

The Little Kilt – The feileadh-beag (pr: feela beg)

The Little Kilt – The feileadh-beag (pr: feela beg)The beginnings of the small kilt – the one which is worn in modern times – has caused lots of arguments over the years. There are many people who like to think that something so Scottish has to be really ancient but it is generally agreed that the little kilt (Feileadh-beag – pr: feela beg ) is really quite modern having first become popular about 270 years ago.

One of the commonest tales is that it came about in the 1730s at an ironworks at Glengarry in Argyll. The manager there was an Englishman called Thomas Rawlinson who wore the kilt himself and noticed the inconvenience of being unable to remove the top half when it became soaking wet with rain, without having to take the bottom part off as well. So he separated the top half and got a tailor to sew the pleats permanently into the bottom half. The Chief of Glengarry – Iain MacDonell – saw this, thought it a great idea and copied it.

Hose

Most Highlanders went around bare-legged and bare-footed but when they did start wearing stockings, they were made of cloth and not knitted like modern ones. The pattern was usually a red and white check which was called cath dath (pr: kaa dah) – war pattern.

A characteristic of traditional hose was that they stopped well below the knee – usually on the thickest part of the calf. Even with garters however, those old diced hose were pretty shapeless and fell down frequently if the wearer didn’t have a good sized calf muscle and they were eventually replaced by knitted stockings which clung to the legs much better.

Garters

There was no elastic in those days and to keep the socks up it’s said that poorer Highlanders would often tie some plaited hay or straw around the top of them to  hold them up. For the better off however, garters were woven on a special hand loom called agartane leem which was also used for weaving narrow strips of fabric. Nowadays it’s called an Inkle loom and was mentioned in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost but the loom predated that period by several centuries.

hold them up. For the better off however, garters were woven on a special hand loom called agartane leem which was also used for weaving narrow strips of fabric. Nowadays it’s called an Inkle loom and was mentioned in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost but the loom predated that period by several centuries.

The woven garters were about a metre long and ended in a special knot called the Sniomh Gartain (pr: snaime garshtan) which is said to be a bit like that on a modern necktie. The village of Cladich on Loch Awe was said to be home to a colony of weavers – almost all of them MacIntyres- who were renowned for their hose and their ‘greatly celebrated”Cladich garters’ which were mostly made in red and white and were greatly prized by pipers. Their fine hose was possibly the forerunner of today’s Argyle pattern. The last MacIntyre weaver in Cladich is said to have died in 1870.

Sporran

Historically, very little seems to have been written about the sporran. The need for such a ‘purse’ however is self evident. In the belted plaid, although the wearer could fashion various pockets from the upper portion of the fabric, none of them were very secure and small, valuable items such as money and lead balls for the musket & pistols, could easily be dislodged and lost. Originally the sporran was carried on the belt – just like a modern holiday maker’s money belt. The’working sporran’ was usually very basic – a large circle of leather with holes punched around the periphery and then drawn together with a thin leather thong and attached to the belt.

For dressier occasions- usually the prerogative of the financially better-off – the sporran was much more ornate and hung at the front, either on the waist belt or on its own sporran belt.

A huge range of indulgent designs appeared with silver cantles and tassels. Most were made of animal skins such as otter, badger, goat and seal and by the late 1800s there appeared the sporan molach or hair sporran usually made from goat skins and so large that it almost covered the front of the kilt.

Belts

BeltsA Highlander’s leather belt was usually made of cowhide and with a brass or silver buckle. If a Highlander was on a long trip and was short of food, he would tighten his belt which made his stomach feel less empty. Some belts were reported as being highly decorated with silver ornaments intermixed with the leather like a chain. The better-off had even more ornate belts and sometimes the end that went through the buckle would be metal or silver that was highly engraved and decorated with fine stones or pieces of red corral.

Hats

Many writings mention the Highlanders’ bonnet – Boineid (pr: bonaje) which came to be called the Tam o’ Shanter. This was knitted or made of cloth and was worn tight around the brow and very loose on top with a toorie for decoration – a bobble or pompom. Bonnets were mostly blue but were also made in brown and grey. In time it became smaller and was known as the Balmoral – boinead biorach (pr: bonaje beerach) which sometimes had a diced band (checked like a chess or draughts board) and the toorie on top. The ribbons at the back were for adjusting the headband so that it fitted all head sizes. Tradition has it that in the army, Lowlanders (those Scots who live south of the Highlands) let the ribbons hang free whilst Highlanders would tie them in a bow.

Over the years, some wearers of the Balmoral wore it puffed up on the head and then creased it down the middle. This produced a new style of hat called the Glengarry. By late Victorian times almost all the British Army wore this type of hat when they were in their working uniforms.

The black knife – Sgian Dubh (pr: skian doo)

The derivation of the name of this little ‘weapon’ is open to discussion. Traditionally the handle was made of black ‘bog wood’ – wood that had long lain submerged in a bog, and that’s certainly an obvious origin. Others point to the fact that originally it was a hidden knife and therefore rather sinister and used for ‘black deeds.’

In rougher ages it was secreted in the oxter – the armpit – and could be withdrawn for use in a flash. As violence and lawlessness disappeared, the need for such a hidden weapon diminished and it was then openly displayed, tucked into the hose top.

Dirk – Biodag (pr: beedak )

Dirk – Biodag (pr: beedak )The Highland dirk grew directly from the early Ballock Knife – an old spelling of the more familiar and vulgar name for the male testes – which was prevalent throughout Western Europe in the Middle Ages. In 1617 a Richard James describes Highlanders as wearing “a long kinde of dagger, broad in ye back and sharpe at ye pointe, which they call a darcke.”

Ideal for close-quarter fighting, the dirk was a long stabbing weapon up to 20 inches in length.

The Dirk Belt

The dirk sheath would often be hung round the Highlander’s waist or attached to a special dirk belt – the criosan biodag (pr: creeshan beedak). That dirk belt became the standard kilt belt that we wear today.

Jewellery

Highlanders were said to be suspicious of money and preferred to carry what wealth they had in the form of jewelry and embellishments to their weapons. Solid silver buttons were one of their favorites and these would often be passed down from father to son. If the Highlander died away from home, it was important to him that he had enough valuables with him that would pay for a good funeral and a headstone.

Plaid brooches or Cairngorm brooches as they are often called – originally because of the Cairngorm stone at their centre. A cairngorm stone is, unsurprisingly, found in the Cairngorm mountains in Scotland and is the brown variety of rock crystal often erroneously called “smoky topaz.” Cairngorm has a sentimental and historic interest involved in its use as an ornament for the weapons and picturesque clan dress of the Scottish High-landers.

Plaid brooches or Cairngorm brooches as they are often called – originally because of the Cairngorm stone at their centre. A cairngorm stone is, unsurprisingly, found in the Cairngorm mountains in Scotland and is the brown variety of rock crystal often erroneously called “smoky topaz.” Cairngorm has a sentimental and historic interest involved in its use as an ornament for the weapons and picturesque clan dress of the Scottish High-landers.

Clan Badges

It’s said that clan chiefs would often give their clansmen a metal plate of their crest which could be worn as a sign of their allegiance. The usual method of fastening  it to their clothing was with a leather belt and buckle and when it wasn’t being worn, the belt was coiled around it. That gave rise to the modern convention that we all know, which is the belt and buckle clan badge worn by clan members the world over – the belt and buckle element displaying their allegiance.

it to their clothing was with a leather belt and buckle and when it wasn’t being worn, the belt was coiled around it. That gave rise to the modern convention that we all know, which is the belt and buckle clan badge worn by clan members the world over – the belt and buckle element displaying their allegiance.

Highland dress encapsulates and transfers to its wearer many of those actual and subliminal images and then of course . . . . there’s the little matter of what’s under that kilt . . . . a puzzle that has occupied the minds and eyes of many a lady (can they really be ‘ladies’?) who from the earliest of European cartoons, have been recorded as being agog with curiosity. So . . . you’ll see by now that Highland dress is cool . . . worn by crusty old colonels of the regiment, strutted on the catwalks of modern fashion icons, turned into mega-entertainment in America’s annual ‘Dressed to Kilt’ show and found in the wardrobes of rich and poor, young and old, slim and fat.

Whew! I think those Scots put more into their wardrobe then the average woman. Really, but I know that my most important feature of a mans kilt is the lack things under it…well, so they say! Otherwise, it’s just a skirt!

So now that I have your mind exploding with Scottish Dress knowledge thanks to Wikipedia and www.tartansauthority.com you can take a moment to soak it all in. Maybe you’re in the market for a Kilt for Christmas? Well, Tartans Authority has you covered.

Now, it’s time to check out Michelle’s book with a sexy Scot on it: Love Potions

Find more information about the WARLOCKS MACGREGOR SERIES on Michelle’s book page

Buy it on Amazon

The post Some like it Scot? It’s in the dress! appeared first on Pillow Talk Blog.

newest »

newest »

In fact, my maternal grandfather, John McIntyre, revived the art of weaving Cladich garter flashes on the shores of Loch Awe, when he and my grandmother had a loom in the village of Lochawe in the 1950s. Some of his weaving survives to this day and the male members of my family have Cladich garter flashes to wear with their hose.

In fact, my maternal grandfather, John McIntyre, revived the art of weaving Cladich garter flashes on the shores of Loch Awe, when he and my grandmother had a loom in the village of Lochawe in the 1950s. Some of his weaving survives to this day and the male members of my family have Cladich garter flashes to wear with their hose.