Retreaded: TechnicalDebtQuadrant

Retread of post orginally made on 14 Oct 2009

There's been a few posts over the last couple of months about

TechnicalDebt that's raised the question of what kinds of design

flaws should or shouldn't be classified as Technical Debt.

A good example of this is Uncle Bob's post saying a

mess is not a debt. His argument is that messy code, produced by

people who are ignorant of good design practices, shouldn't be a

debt. Technical Debt should be reserved for cases when people have

made a considered decision to adopt a design strategy that isn't

sustainable in the longer term, but yields a short term benefit,

such as making a release. The point is that the debt yields value

sooner, but needs to be paid off as soon as possible.

To my mind, the question of whether a design flaw is or isn't

debt is the wrong question. Technical Debt is a metaphor, so the

real question is whether or not the debt metaphor is helpful about

thinking about how to deal with design problems, and how to

communicate that thinking. A particular benefit of the debt metaphor

is that it's very handy for communicating to non-technical people.

I think that the debt metaphor works well in both cases - the

difference is in nature of the debt. A mess is a reckless debt which

results in crippling interest payments or a long period of paying

down the principal. We have a few projects where we've taken over a

code base with a high debt and found the metaphor very useful in

discussing with client management how to deal with it.

The debt metaphor reminds us about the choices we can make with

design flaws. The prudent debt to reach a release may not be

worth paying down if the interest payments are sufficiently small -

such as if it were in a rarely touched part of the code-base.

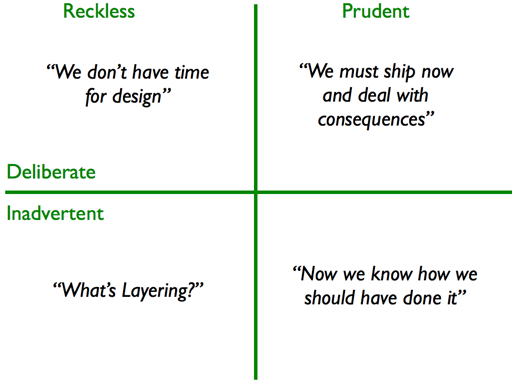

So the useful distinction isn't between debt or non-debt, but

between prudent and reckless debt.

There's another interesting distinction in the example I just

outlined. Not just is there a difference between prudent and

reckless debt, there's also a difference between deliberate and

inadvertent debt. The prudent debt example is deliberate because the

team knows they are taking on a debt, and thus puts some thought as

to whether the payoff for an earlier release is greater than the

costs of paying it off. A team ignorant of design practices is

taking on its reckless debt without even realizing how much hock

it's getting into.

Reckless debt may not be inadvertent. A team may know about good

design practices, even be capable of practicing them, but decide to

go "quick and dirty" because they think they can't afford the time

required to write clean code. I agree with Uncle Bob that this is

usually a reckless debt, because people underestimate where the

DesignPayoffLine is. The whole point of good design and

clean code is to make you go faster - if it didn't people like Uncle

Bob, Kent Beck, and Ward Cunningham wouldn't be spending time

talking about it.

Dividing debt into reckless/prudent and deliberate/inadvertent

implies a quadrant, and I've only discussed three cells. So is there

such a thing as prudent-inadvertent debt? Although such a thing

sounds odd, I believe that it is - and it's not just common but

inevitable for teams that are excellent designers.

I was chatting with a colleague recently about a project he'd

just rolled off from. The project that delivered valuable software,

the client was happy, and the code was clean. But he wasn't happy

with the code. He felt the team had done a good job, but now they

realize what the design ought to have been.

I hear this all the time from the best developers. The point is

that while you're programming, you are learning. It's often the case

that it can take a year of programming on a project before you

understand what the best design approach should have been. Perhaps

one should plan projects to spend a year building a system that you

throw away and rebuild, as Fred Brooks suggested, but that's a

tricky plan to sell. Instead what you find is that the moment you

realize what the design should have been, you also realize that you

have an inadvertent debt. This is the kind of debt that Ward talked

about in his

video.

The decision of paying the interest versus paying down the

principal still applies, so the metaphor is still helpful for this

case. However a problem with using the debt metaphor for this is

that I can't conceive of a parallel with taking on a

prudent-inadvertent financial debt. As a result I would think it

would be difficult to explain to managers why this debt appeared. My

view is this kind of debt is inevitable and thus should be

expected. Even the best teams will have debt to deal with as a

project goes on - even more reason not to recklessly overload it

with crummy code.

reposted on 19 Nov 2014

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1103 followers