The ‘Aha!’ Moment and Three Things That Didn’t Happen in The Montmaray Journals

Working my way through my towers of 1960s research books last week, I finally had an ‘Aha!’ moment – one of those moments when I come across a reference (often a fleeting one, sometimes a mere footnote) to a fascinating real-life event that seems to fit perfectly into my planned story. “Aha!” I cried, clapping my hands in great excitement.1 Ideally, an ‘Aha!’ historical event will involve some bizarre element but not be widely known, because I like the idea of my readers saying to themselves while reading, “I never knew about that! Did that really happen?” On the other hand, it’s helpful (for both me and inquisitive novel readers who want to learn more) if there’s a fair amount of information available about the event. This particular event I’ve discovered appears to fulfil all these conditions, which makes me very happy.

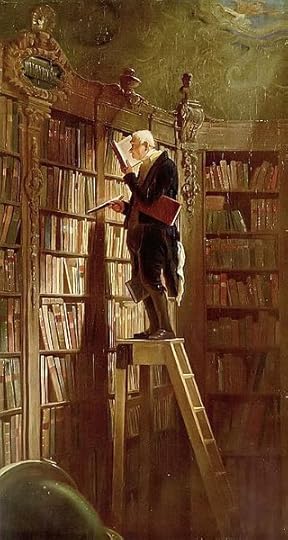

The historical novelist may need to read a LOT of books before an ‘Aha!’ moment arrives . . .

Of course, there’s the possibility that this will turn into an ‘Oh no . . .’ moment, which occurs when I dig further into the research, unearth an inconvenient fact and realise that the event is not actually going to fit into my story the way I’d hoped. Sometimes the dates don’t match my planned story; sometimes there’s a complicated backstory to the event that will lead my story somewhere I don’t want it to go. Here are three scenes that didn’t appear in my Montmaray Journals trilogy, due to ‘Oh no . . .’ moments:

1. Fascists Storm the British Embassy in Madrid!

I came across this thrilling tale in the memoirs of Sir Samuel Hoare, Viscount Templewood. Hoare was an fervent appeaser of Mussolini and Hitler in the years before the Second World War2, and so, not surprisingly, lost his ministerial job when Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940. Churchill sent Hoare to Spain to keep him out of the way, figuring Hoare couldn’t do too much damage there and might even get along quite well with Franco, Spain’s Fascist dictator – maybe even persuade Franco to renounce Hitler. Of course, Franco paid no attention to Hoare whatsoever and continued to co-operate with the Nazis whenever it was in his interests to do so, turning a blind eye when his Falangist supporters, with the help of Nazi agents, attacked the British Embassy:

“The attack had in all respects been methodically planned in the true German manner. It was to begin with the burning of the British staff cars standing outside the Embassy. It was at this point that Spanish forgetfulness frustrated German efficiency. Matches were then very scarce in Madrid, and either no one had a match or no one wished to sacrifice one in a street battle. The cars, therefore, escaped burning though several were seriously damaged by stones.

The next move was an attempt to break into the Embassy. At this point we [Embassy staff] were in a strong position. For not only were we protected by our regular force of British guards, but we had within the precincts sixteen of our escaped prisoners of war who were burning for the chance of a battle with the enemy . . .”

Wouldn’t it be great, I thought to myself, if Toby FitzOsborne, recently escaped from Nazi-occupied France, could be one of those men in the Embassy battling the Fascist invaders! With Veronica fighting beside him, knocking out a few Falangists with a well-aimed chair! Alas, the dates just didn’t work out. The Embassy attack occurred in June, 1941, when Toby was still flying in combat as an RAF fighter pilot and Veronica was working in the Foreign Office in London. Anyway, Hoare was not exactly a reliable memoirist, so I suspect the British response during the Embassy siege was a lot less brave and glorious than he described.

2. Sophie FitzOsborne, Lady War Correspondent

I carefully added some references to Sophie writing newspaper articles in the second Montmaray book, so that once war broke out, I’d be able to turn her into a newspaper reporter and send her overseas, in order to describe lots of important battles. But when I started researching the lives of actual war correspondents such as Martha Gellhorn3, I realised this was never going to work. Sophie just wasn’t tough or experienced enough – no British newspaper editor would ever employ her as a reporter, not even to report on the London Blitz. It wasn’t even likely she’d get a job as a women’s columnist – British newspapers were severely curtailed during the war, as a result of both paper shortages and official censorship, with only essential news being printed. In the end, I decided I preferred her to have a humdrum job during the war, to emphasise that war, for most participants, is the exact opposite of a noble, exhilarating experience. And Sophie did get to write some Food Facts, which were published to help housewives cope with rationing. Also, did you know that Eileen O’Shaughnessy, George Orwell’s wife, worked at the Ministry of Food during the war? I tried to arrange a friendship between Sophie and Eileen, so that Sophie could have a discussion about totalitarianism with Orwell, but unfortunately, the two women worked in different departments.

3. The Spy, The Cryptographer and The Poet

During the war, the Special Operations Executive sent Allied agents into occupied Europe, with the agents communicating using codes that were initially based on well-known poems. Unfortunately, these poem ciphers were very easy for the Nazis to break. Leo Marks, a British cryptographer in charge of SOE agent codes, made a number of changes to ensure the codes were more secure, including using original poems. Aha! I thought. Maybe Sophie and her friend Rupert, with their flair for poetry, could meet to write poems for Leo Marks! Unfortunately, introducing another real-life character and his complicated backstory would have made my book even longer than it already was (that is, far too long), so that plot line was dropped. However, I did manage to sneak in a reference to Leo Marks – the Colonel mentions an anonymous friend who is “one of our best cryptographers” but has failed to decipher a sample of Kernetin, the FitzOsborne family code.

Incidentally, Leo Marks was the son of Ben Marks, one of the owners of Marks and Co, the famous bookshop at 84 Charing Cross Road – and an employee of that bookshop just happens to be related, in a very tangential way, to that exciting thing I discovered in my 1960s research. Aha! The plot thickens . . .

_____

Probably only historical novelists would describe this sort of discovery as ‘greatly exciting’. ↩

For example, in March, 1939, after the Nazis had invaded Czechoslovakia, Hoare stated that he remained optimistic that Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin would become “eternal benefactors of the human race”. ↩

I was also tempted to have Veronica meet Martha Gellhorn’s close friend, Eleanor Roosevelt, during the First Lady’s visit to England in 1942, because I figured those two would have a very interesting discussion. But there were just too many other events going on in the plot at that time. ↩