Captain Hank Parker – Battery Commander – Part Nine

HANK PARKER

Part Nine

The Empty Parapet

July is a tough month with mortar attacks almost every night and casualties mounting. We start a policy that you have to wear your steel pot and flak jacket 24/7. It is miserably hot, but when you are outside you have to have them on and we enforce that.

With less than a week to go in Vietnam Lieutenant Monahan is standing in the middle of the battery. Bullets start flying, popping up sand around his feet. He heads for his hooch, I guarantee, and there he stays. That’s the smart thing to do. He leaves LZ Sherry just before the attacks that kill Theodus “Yodo” Stanley and Howard “Howie” Pyle Jr., and wound eight others. (August 12, 1969)

The evenings start with such beautiful sunsets, lovely, but when the sun sets I get migraine headaches. Miserable. I go to the beer hooch and get a little liquid courage, knowing I’m going to get up, put on my steel pot and flak jacket and go around to the guns and up in the towers and talk to the guys. If they are having difficulties they tell me – with a girlfriend or a situation at home. I need my flashlight with me, oh God, how dark it gets. I am petrified walking around at night knowing what is out there, and waiting for the rounds to fall.

I tell the guys on all the guns that we’re in an area where there is significant infiltration, and we’re talking battalions. We’re not talking little squads of black pajama’d Viet Cong, we’re talking regular People’s Army of North Vietnam, thousands of them. They know what they are doing and they want to get us. Most importantly we need to be prepared to lower those tubes for direct fire if there is a ground attack. I tell the gun chiefs to have fuses cut and ready for beehive rounds for direct fire.

I stop to chat with Sergeant Groves and his crew on Gun 2. I am close to him, because he is a nitpicker, and let me tell you, if you trained on Rik Groves’ gun you are never going to be wrong on your deflection (direction) or elevation on your howitzer, and you are never going to put the wrong powder charge in. I know because when fire missions were going on I would go around and check the deflection and elevation on the guns to make sure we were doing it right. There are a couple guns I have to watch, a little bit sloppy with deflection and elevation. I tell them, “There’s no room for error. The slightest error in deflection or elevation when it goes six miles out it’s enough to hit and kill the wrong people.” (A deflection error of one degree results in an impact error of 185 yards at six miles.) I never worry about Guns 2 and 3 – or Gun 5 where Dave Fitchpatrick is chief. He’s fun loving and runs a tight crew.

I always stop to talk with Corporal Howie Pyle (crew chief on Gun 3, which is base piece in the center of the gun emplacements and the gun on which firing data is figured for all the guns). When I was a Forward Observer I would come to Sherry and make a special point of talking to Howie. His gun was base piece and I wanted to make sure that he knew what he was doing, and his crew knew what they were doing. Well he showed me, and they were good. I got to know his crew, and I could always depend on them, especially when I called in first round high explosive.

Howie is my age and has some college like me. He is genuinely interested in what I did as an forward observer out in the field with the infantry. He is bright, articulate, and has the respect of his men. I tell him he could be in my shoes and I could be in his. I say, “You have the brightness and the ability, you just chose not to go to officer school.” We talk about our families. His father was WWII, and my father was post occupation WWII. We share stories like that.

Sometimes Tommy Mulvihill joins us. The two of them are best friends. They are both from around New York City and tell me Howie is from Pleasantville near Sleepy Hollow, and Tommy is from Hicksville. I say, “You guys are pulling my leg. Those aren’t real places.” (They are.)

The first attack comes in the early morning hours and the second comes late at night. I am fairly certain we are being attacked by a North Vietnamese Army crew that knows how to fire mortars, because in both attacks they walk them right through the battery.

My memory compresses the two attacks into one, even though they come over 20 hours apart. In the early dark I hear a mortar pop from its tube, I know the mortar is on the way, I run out yelling, INCOMING. The crews are now manning their guns and I am between Guns 2 and 3 conducting a crater analysis taking the back azimuth. I see gun 2 getting hit and I see Stanley go down. Sergeant Groves is wounded in the neck. His face is ashen white just like his hair. He goes down and cradles Stanley while holding his own neck, trying to stop the both of them from bleeding.

As I say, my mind compresses everything, and now I look over at Corporal Pyle on base piece. He gives me a quick grin like he always does, his eyes bright and sharp. Just as he’s smiling I see the round hit the platform under the gun. I see Howie and his entire crew go down. The ground is shaking, the dirt is flying. Again I smell the cordite mixed with blood.

Seconds become minutes, and minutes become hours. Time slows and I see things in slow motion. First Sergeant Durant and Chief Cerda are there taking care of the guys and yelling MEDIC, MEDIC. Doc comes. Tommy is immediately over on Gun 3. He takes Howie away from Durant and holds him. Mortars are still falling. One guy is writhing in pain. Another I push his wound closed and tell him to hold it. He says, “Am I going to be OK?”

I say, “Yeah, you’re going to be OK,” but I don’t believe it. I think all those guys will die. I’ve never seen so much blood in my life.

The tires on Gun 3 are blown but it is still functional. You can put a round in the tube, you bet, so it’s still good for direct fire. I am afraid this is the night they are going to try to come in, so we manhandle the gun out of its sandbag parapet and drag it to the perimeter. I get available guys and we pull it out by the helipad in the direction of the streambed. That part of the perimeter is a weak point. Fortunately we’ve got beehive rounds already prepared. The Dusters’ 40 mm cannons are firing, the Quad 50 machine guns are firing, the towers are firing. I am fully prepared to see a ground attack, because their mortar fire has knocked out two guns and the mortars are still coming down. Through it all I am amazed at the efficiency of our artillerymen. They are able to provide counter fire, take care of the wounded, and secure the perimeter. No ground attack comes that night because – and I firmly believe this – our counter mortar fire prevented any ground attack they may have planned.

When things finally go quiet and the battery is secure and we’ve cared for the dead and wounded, I go back to the empty Gun 3 parapet. I get a lawn chair and a six pack of beer and sit down. I make it clear I want to be alone. I want to mourn. That’s when the full emotional impact hits me, all the casualties we suffered. I have my M-16 and .45 pistol with me. I am drinking and firing into the air and screaming at the enemy, “Lucky shot, come on and let me see you do it again.” Just angry, angry, and I want to fight. I drink a lot of beer that night and fire a lot of rounds at nobody.

Of all people, here comes Tommy Mulvihill. He walks up to me and says, “Lieutenant, you OK?”

I say, “I don’t know yet. This hurts.” Like it or not I am their leader and to loose two gun crews is a failure in leadership. I take it personally. I’ve grown close to Rik and Howie and Theo and the guys wounded who I think are going to die. I am suffering. Yet here is Tommy Mulvihill who just lost his best friend and he’s concerned about me. He’s the only one with the guts and the balls to come talk to me. And that moves me. Passion and concern for me, am I OK?

Theodus (Yodo) Stanley

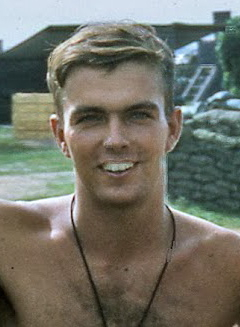

Howie (Gomer) Pyle

At that moment, a profound moment, I recognize that I have had the distinct honor of working with some of the best people in the world and that B Battery at LZ Sherry is special. When I saw the compassion and the warmth and the tenderness that these guys provided for one another amid the carnage, I was moved and drew closer to these men. And I vow at that moment that there will never be a gun back in this parapet. It is now sacred ground. Stanley didn’t die here, but here is the memorial to all of the fallen this night.

On the last Medevac helicopter out that night I am surprised to see our battery commander, The Ghost, getting on the skid of the helicopter to leave. I look at him and he looks back at me. I am puzzled. I put my hand up and say, “What are you doing? Where are you going?” I don’t see him again until a year later at Ft. Sill.

First Sergeant Durant later tells me he had called the battalion sergeant major about our battery commander. Durant was always out doing crater analysis by himself during mortar attacks when the captain should have been with him. Durant said to him, “Sergeant Major, you get me somebody out here who is at least going to go out with me during the attacks.”

My guess is the captain was relieved after the August 12 attack, or he asked to be moved. I don’t find a problem with that. If a person does not have the command ability or the command presence in combat situations, that’s something you have or you don’t have. If you don’t have it I think it’s wise to work somewhere else. I’m sure that’s what they did with this captain.

I, along with a lot of other guys, wonder why the round that fell on Gun 3 was so deadly. I’d never seen a round take out that many people that quickly. Pyle had a puncture wound that came out his back. Doc Townley said it looked almost like a fleshette wound. But they didn’t make fleshettes rounds for mortars. Typically we’re used to mortars coming in and hitting in the sand, burying and then exploding. This mortar hit the wood platform under the gun. It exploded higher in the air than if it had hit sand, shooting medal shrapnel through the air and creating secondary shrapnel in the form of large wood splinters. The combination was especially lethal. My yelling “lucky shot” in the parapet that night was probably correct.

Gun 3 parapet stood empty in the center of the battery for the remainder of B Battery’s time in Vietnam. Likewise no howitzer was ever again labeled Gun 3.

Gun 3 parapet stood empty in the center of the battery for the remainder of B Battery’s time in Vietnam. Likewise no howitzer was ever again labeled Gun 3.