It ain’t a Fall if it’s a Bow

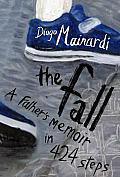

THE FALL: A Father’s Memoir in 424 Steps by Diago Mainardi

THE FALL: A Father’s Memoir in 424 Steps by Diago Mainardi

I don’t know how Other Press does it. They just find these books that, in like 10,000 words, less than 200, digest-size pages, rip me to my gut. They’ve done it again with Diago Mainardi’s The Fall: A Father’s Memoir in 424 Steps.

You can’t even call it heart-breaking, just gut-twisting full of emotions. It’s the story of a father and his hero, his muse, his son, Tito, a boy born with Cerebral Palsy after the hospital made a mistake during his birth. It’s less a guide from Mainardi on how to deal with raising a kid with this condition, never a whine that his kid isn’t normal, but truly, a celebration and not-so-humble brag about why this little guy who has never walked more than 424 steps at a time without falling down is the best kid ever.

The story does, I guess, start off sad. The first steps – and the whole book is like this, pieced off into paragraphs that make up “steps” instead of chapters, filled loosely with photographs and pictures – outline his wife’s pregnancy, the bad jokes Mainardi made as she went into labor about never having a kid that could rival the architecture of that hospital, the mistakes nurses and doctors made by not delivering Tito as they should have, thus causing his Cerebral Palsy. More than anyone, though, Mainardi blames himself for Tito’s condition. He blames his bad jokes, he blames the things he said (the same things that any father might say), even blames the destiny of all history leading up to this point. Despite all the early blame, though, you can tell Mainardi doesn’t actually care about the circumstances; he’s a thankful bastard he’s got the son he has today.

Maybe mid-way through begins just the best gushing/fawning over a kid in modern literature. Doctors say his kid will never learn to talk; Mainardi writes about the genius of his son who created his own secret language that his whole family can crack like their special code. Doctors say his kid will never learn to walk; Mainardi counts the steps his son can take in a row before “the fall,” which is inevitable. Practicing on the beach, Tito learns slowly, taking a few steps at a time before landing in the sand, giggling as if a joke rather than getting stumped by the defeat. The number grows and grows, Tito gets farther before falling down (never losing the attitude that it’s okay to fall over). Eventually this kid, this little wobbly boy that nobody expected to move on his own or communicate, takes 424 steps. It’s a marathon. It’s a hell of a lot.

Basically this: If you’ve got a kid, you’ll know what it’s like to be so proud of them, from the first time they throw up and don’t get it all over your shirt to the first time they count to ten, and you’ll relate to the gushing-dad in Mainardi. If you don’t, and you know anyone with anything setting them back, anyone who’s overcome anything everyone talked against, your face is gonna glow with the same pride while reading this. And, if you’re not in either of those groups, you’re gonna need to read this book anyway, because it’s time you see some of the beauty this world’s got.