Wamblecropt, nurdle, autumn and other favourite words

By CATHARINE MORRIS

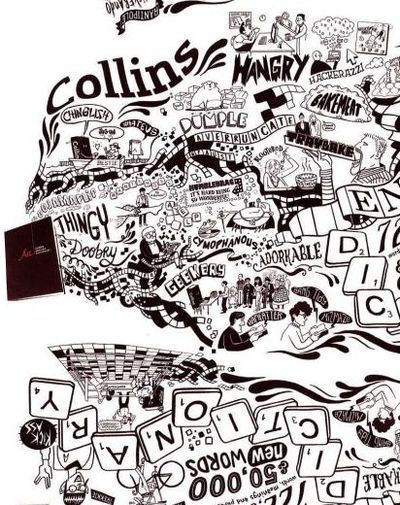

“The great thing about a dictionary”, said Mark Forsyth – the author of The Etymologicon (2011), among other books – at the launch of the new Collins English Dictionary at Waterstones Piccadilly a couple of weeks ago, “is that you can start anywhere and finish anywhere”. “I go to a dictionary to look up a particular word and I find – ah yes, ‘Agnate’ means ‘sharing a common male ancestor’ or whatever it happens to be and then my eye just sort of drifts, so I discover that there’s a word ‘aglet’ meaning the small bits of plastic on the end of your shoelaces . . . and then my eye drifts further and further and further and eventually I come to look at my watch and discover that it’s February”.

The theme of the evening was favourite and least favourite words (the TLS contributor David Collard has written very entertainingly on the topic from an aesthetic point of view; you can find his blog posts here and here). Our host, the journalist Lucy Mangan, asked Forsyth, who provided the introduction to the new dictionary, what qualities he looked for in a word. “It’s wonderful when a word means something very, very specific . . . like ‘gongoozle’ – I remember finding that in a dictionary of canal terminology . . . . Gongoozle means ‘To stare idly at a canal or other watercourse and do nothing’ . . . . I have since discovered that it is still extant in the houseboat community”. He also offered “sprunt”, used in the Roxburgh district of Scotland in the early nineteenth century, which means “to chase girls around among the haystacks after dark”; and “mamihlapinatapai”, used by the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego at the tip of South America, which he defined as “two people looking at each other both wanting to do the same thing but neither wanting to be the person to do it”. (When Mangan said that it should be a British word, Forsyth agreed: “It describes every kiss I’ve ever had”.)

Forsyth is attracted by the sound of certain words. He loves “wamblecropt” (“overcome with indigestion”) and “snollygoster” (which means "dishonest politician"), “a nineteenth-century American word which has since died out because all politicians are now honest”. Then there are the “lovely etymologies”. Forsyth is keen on “ultracrepidarianism”; this he defined as “giving opinions on things you know nothing about, which I do professionally”. The OED says of ultracrepidate: “Etymology: the Latin phrase ultrā crepidam ‘beyond the sole’ in allusion to the reply of Apelles to the cobbler”. I had to look up Apelles and the cobbler. Apelles is the artist Apelles of Kos (fourth century BC), and the story goes that, having overheard a cobbler saying that a shoe in one of his paintings looked wrong, Apelles repainted it; but when, buoyed by this little triumph, the cobbler moved on to criticize other parts of the painting, Apelles was incensed: “The cobbler should go no further than the shoe!”

Mangan had spotted the word “nurdle” on Forsyth’s website. A nurdle is the small amount of toothpaste you squeeze on to your toothbrush. “In the toothpaste industry, the nurdle is a big thing”, Forsyth told us. He described a court case involving two toothpaste manufacturers that was “all about nurdles and the depiction of nurdles” on the toothpaste packaging. “The word ‘nurdle’ cropped up several hundred times in the court papers.” No mention of the toothpaste nurdle in Collins; but it does give the cricketing term: “To score runs in cricket by deflecting (the ball) rather than striking it hard”.

The least favourite words mentioned during the discussion were in fact least favourite usages. Forsyth hates the use of the word “individual” to mean “person”; and “real” in phrases such as “real people” and “real life”: “‘Real life’ merely means my life and the lives of my friends and all the people I speak to down the pub”. The audience chipped in with the phrase “common sense” and “like” as a filler word. (“I think ‘like’ gets a slightly bad press”, Forsyth said; “we all use filler words . . . . ‘I mean’ and ‘well’ are the ones used by the older generation. ‘Like’ is used by the younger generation.”)

One favourite word (submitted via Twitter) was “Autumnal”, which prompted Forsyth to share “petrichor”, a new addition to the Collins dictionary, which is defined there as “a sweet smell that is produced when rain falls on parched earth”.

When people talk about favourite words, Forsyth observed, they tend to choose obscure rather than normal ones. This reminded me of the poem “At The Pillars” by Hugo Williams, written in memory of Mick Imlah, which was published in the TLS at the beginning of this year:

Everyone was saying their favourite word.

Yours was “suddenly”.

Other members of the herd

chose something funny or absurd,

“lackadaisical” or “haphazard”.

We were laughing and drinking happily,

saying our favourite word.

Yours was “suddenly”.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers