How I (barely) survived indexing an academic monograph

I have just spent the most wonderful week and a half of my life indexing my academic monograph. Few people, on their deathbeds, are reported as saying that they regret not spending enough time indexing their academic monographs; I feel there may be a reason for that.

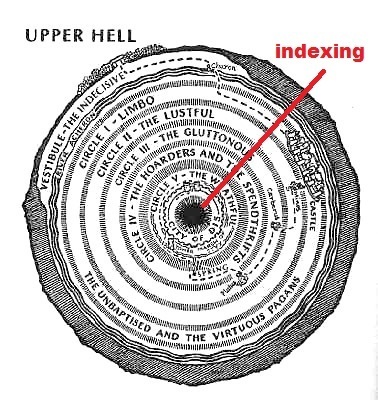

The exact location of indexing as Dantesque punishment

Indexing, it turns out, is not only yawn-inducingly tedious; it is also much more difficult than I expected, and requires complete concentration. It is also one of these word-tasks which gradually empties all words of any meaning, to the extent that my book subtitle – Time and Power in Children’s Literature – now means stricly nothing to me, apart from the ‘and’ and ‘in’ that I didn’t have to index.

However, I must admit that indexing was also quite an interesting task in places, and taught me quite a few things about the way I write, the way I read, and the bizarre genre that academic monographs belong to. I thought I’d share a few insights about the painful process.

Firstly, just a few notes on the way it gets done (for me, at least):

When I got my first proofs, I was asked to give two lists of entries (proper names, and nouns) to the publisher to constitute the index. My original list had roughly 300 noun entries. Because a software was going to be used to generate concordances, I had to submit several spellings for similar terms: not just ‘empathy’ but also ‘empathise’, ‘empathetic’, etc. (so yes, ‘empathy’ is now totally devoid of meaning too).

Alongside the second proofs, the index came back with the page concordances. It looked a bit like this, everywhere:

désir et le temps 44, 49

desire 2–5, 7, 9–10, 19, 22, 27–28, 30–36, 39–41, 43–46, 49–51, 54–56, 58–59, 62, 69–71, 74, 77–79, 82–84, 86–95, 97–101, 104, 106, 127, 131–135, 139–140, 143, 153–154, 157, 165, 169, 172, 176, 178, 180, 186–193, 195–196, 199, 203–205, 207–209

didactic 2–4, 6–7, 9–10, 18–19, 36, 38–39, 41, 43, 46, 48–49, 53, 56–58, 63, 65, 69–75, 77–91, 93–94, 98–101, 106–109, 111, 117, 120, 122–123, 131–137, 140, 143, 147, 150, 152, 155–157, 161, 170, 176, 178, 184, 186, 188, 190–191, 194, 197–198, 203–204, 206–209

didactically 4, 156

Of course, the damn book being about children, children’s literature, and childhood, there were some particularly hellish lists of concordances for the terms in question:

childhood 5–11, 15–20, 22–25, 27, 34–35, 37, 40–41, 43, 46, 48–49, 51, 55–59, 71, 83, 85–89, 91–92, 96–97, 99, 104–109, 112, 114, 128, 130–131, 154, 166, 170, 176, 178, 180, 182, 186, 188, 192–195, 197–198, 205–206

child 2–11, 15–27, 34–36, 38–41, 43–44, 46–50, 52–65, 70–101, 103–110, 112–114, 117, 119–121, 123, 128, 130–131, 133–136, 143, 147, 150–152, 154–157, 160, 162–163, 166–188, 190–209

child reader 2–4, 7–8, 10, 40, 47–48, 58, 63, 71, 73–74, 78–82, 91–92, 94–100, 112–114, 117, 128, 130–131, 133, 135–136, 143, 147, 150–151, 154, 156–157, 160, 162, 167, 169–171, 174, 176, 179–180, 182–183, 198–203

children’s literature 2–9, 15–20, 22, 25–27, 33–34, 40–41, 43, 46–59, 62, 65, 70–72, 74–75, 77–81, 85–86, 89–91, 94–100, 105–106, 108–113, 118, 122–123, 131–135, 147–156, 161–163, 169–171, 174, 178–186, 192, 195–198, 202, 204–209

I sat down with much tea, for days and days on end, and went through the proofs, and slowly cut down, merged, subdivided and split those ginormous lists of page numbers, using subentries. I Ctrl+F’ed by way through the electronic proof instead of printing out a paper proof, because 1) trees are dying and 2) it’s much easier.

So what did I learn, dear readers?

Some concepts are just too damn large

I was primordially mystified about one thing: how do you index a term that is quite literally central to the whole book? In my case, it seemed difficult to index ‘time’, ‘power’ and ‘children’s literature’ in any other way than by saying ‘Read the whole damn book, you lazy sloth’.

I sought inspiration in academic monographs I happened to have lying around, such as Peter Stearns’ (excellent) Anxious Parents: A History of Modern Childrearing. How, I wondered, did Stearns index the term ‘anxiety’?

That’s right. Eight page numbers or ranges. I was pretty sure I’d seen the word ‘anxiety’ or ‘anxious’ something like a hundred times more throughout the book, but I was curious to see which occurrences Stearns had decided to index.

That’s right. Eight page numbers or ranges. I was pretty sure I’d seen the word ‘anxiety’ or ‘anxious’ something like a hundred times more throughout the book, but I was curious to see which occurrences Stearns had decided to index.

So I checked. And apart from an introductory bit (p.11) and a conclusion bit (215-216, 222) which were vaguely about definitions of anxiety, the other choices of pages were totally incomprehensible. Why pick those? I have no idea. If I had done Stearns’ index, I would have had subentries of the type: ‘health-related’, ‘about achievement’, ‘class-related’, ‘definitions of’, etc. An entry like this is of no use at all.

But at the same time, the truth is - as a reader, I didn’t care. I have a book in my hands called Anxious Parents. I read it from cover to cover, in part because it’s quite an entertaining book, and also because I needed the whole of it. I didn’t need to refer to the index to tell me where to find bits about anxiety. Still, it wasn’t a very satisfactory entry.

Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble has a nice, very detailed entry for ‘gender’, but then random entried here and there: for instance, ‘reality of gender’, and ‘construction of gender’, which are not cross-referenced under ‘gender’. I don’t know why.

I then opened Stephen J. Ball’s Class Strategies and the Education Market, and looked for, well, ‘class’:

Quite a lot more detail here. This is a pretty good entry, I thought – clear, broad enough subentries, cross-referencing with middle and working class, which sounds very logical. However, having read the whole book, I can’t help but feel that frankly, Ball’s thoughts on class would be quite simplified and decontextualised if I were to simply pick my way through it thanks to the index.

Quite a lot more detail here. This is a pretty good entry, I thought – clear, broad enough subentries, cross-referencing with middle and working class, which sounds very logical. However, having read the whole book, I can’t help but feel that frankly, Ball’s thoughts on class would be quite simplified and decontextualised if I were to simply pick my way through it thanks to the index.

But then again, it wouldn’t have occurred to me before to use an index to look for the central concept in a book. Who does that?? And suddenly a new diabolical thought came to my mind:

Sometimes, you just don’t want to help the reader.

Seriously: do I want my readers to pick their way through the central concepts in my book?

Sure, I could put a subentry to ‘children’s literature’ saying, for instance, ‘definition of’. But that’s just asking the lazy reader to read just that definition and not take into account the pages and pages and pages of articulate and cogent reflection (sure) that have led to it.

By that time I was fuming, hungry, bored (and also getting dozens of hate emails per minute, but that’s another story) and ready to strike out at those virtual bad readers of the book I was imagining. I spent hours on those pages and pages of articulate and cogent reflection, you scroungers!

I suddenly felt like my index was exposing my poor little book to immoral cherry-pickers, ready to quote definitions entirely out of context. At the same time, I couldn’t quote a whole range of pages before the definition, or it would confuse the hell out of the immoral cherry-pickers and they’d close the book.

So I wanted to help some readers. Just not all readers.

Eventually, I decided to keep it broad and clear like in Ball’s book, but with subentries obscure enough that they couldn’t be relied on entirely out of context; ‘childhood’ became, for instance,

childhood temporal otherness of 6, 15-20, 22–25, 56-58, 71, 104-108, 150, 170, 194; symbolic 7-11, 40–41, 55-56, 71, 85, 88, 154, 170; as associated to hope 46-48; in the didactic discourse 85–89; and subjectivity 96–97; Beauvoirian approach to 104–108, 112, 192–195.

You can really have fun with some entries

This is something I wouldn’t have believed in the first few hours of the terrible task, but I realised that some entries at least offered elegant narrative possibilities. Specifically, the not-huge-but-still-quite-important-concepts. I’ll give you my favourite one here:

disempowerment of the adult 3, 7, 57-58, 65, 113, 124-131, 205; of the child 17–18; of child and adult 176-178, 190 see also power

I’m proud of this one because it’s quite clever. You see, the whole book is about how children’s literature is not as disempowering for the child as much children’s literature theory seems to think it is (see previous article for more details). In fact, in my analysis, children’s literature, more often than not, betrays an adult lack of power.

So this little entry indicates quite neatly what happens in the book: ‘disempowerment of the adult’ has far more page entries than ‘disempowerment of the child’, and the last subentry (‘disempowerment of child and adult’) indicates that we’re talking here about a phenomenon that is also common to both.

I’ve managed entries like that here and there, but not as many as I’d like; they’re my favourite, and if they were little puppies I’d pat their heads and give them treats.

Those horribly overlapping entries!

Inevitably, some entries are going to overlap. You can’t talk about ‘time’ without it overlapping with ‘futurity’, or ‘existence’ without it overlapping with ‘existentialism’. In a way, it could be worse: I actually discovered, doing the index, that I’m thankfully not too bad at using words rigorously enough that I don’t use different ones to mean the same thing (thank you, French education of torture and trauma).

But even so; the worst entries were ‘power’, ‘might’ and ‘authority’, because in my book’s theorisation, ‘power’ is split into two kinds : might and authority. So how do you index those and cross-reference them? And how do you make sure that people are actually going to look up ‘might’ and ‘authority’ instead of just ‘power’?

Well, I created a very inelegant subentry for ‘power’ which I called ‘dynamics of the adult-child relationship’ and which contains a lot of page numbers; and then I finished that subentry by saying ‘see also authority, might’; which I also did for ‘authority’ and ‘might’.

It feels redundant and awful; but it makes sure that a reader will look at authority and might. Since ‘power’ is a central concept in the book, I want to force the reader out of this entry through sheer boredom of all those numbers. The ‘authority’ and ‘might’ entries are much clearer and more reader-friendly, so the reader will jump on those instead.

That was, at least, my reasoning. Maybe I have a manipulative personality, or I’m good at mind games; you decide.

How specific should the subentries be?

From Stearns’ completely nonspecific entries to a complete avalanche of subentries, my bookshelf was full of different approaches. If you want to get an index-inferiority-complex, Education and the middle class, by Sally Power et al, is your book:

Note the final ‘university entry, 95-6′ and ‘university studies, 95-6′. That, my dears, is commitment to indexing.

But seriously, it can get a bit surreal:

‘neglected in sociology of education’? Really? Do we need this entry? Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s a good idea that it’s there, but the implications are shudder-inducing. Should I have a subentry saying ‘unnecessarily guilt-tripping the child into saving the environment’, under ‘ecological books’? There seems to be no limit to where this kind of subentry can lead you – you might as well rewrite the whole book in index form.

‘neglected in sociology of education’? Really? Do we need this entry? Don’t get me wrong, I think it’s a good idea that it’s there, but the implications are shudder-inducing. Should I have a subentry saying ‘unnecessarily guilt-tripping the child into saving the environment’, under ‘ecological books’? There seems to be no limit to where this kind of subentry can lead you – you might as well rewrite the whole book in index form.

As you can see, this week and a half in the circles of hell has triggered some half-annoyed, half-intrigued reflection on the matter. Above all, it’s made me think that I can’t imagine giving the job to anyone else: at least for an academic monograph, you really need to know the whole damn book by heart, and only one person is sad enough for that: the author.

Clémentine Beauvais's Blog

- Clémentine Beauvais's profile

- 301 followers