The Giftedness Project (2). Giftedness and the (Un)happy Child

Part of a blog series on my current research project. Click here for Part I (I will be assuming from now that readers are aware of my views regarding the constructedness of the term, and its ideological problems).

Is it worth sacrificing the current happiness of a child in order to ensure her future happiness as an adult?

What is a happy childhood?

These questions are implicit in many current anxieties regarding child ‘giftedness’; particularly the worry that ‘gifted’ children, whether or not the offspring of ‘pushy parents’, are less happy than ‘normal’ children and are more likely to experience mental health and/or social problems. (I’ll write about ‘pushy parents’ another time, because it’s a very complex question.)

The claim stems from a genuine interest in child wellbeing. This interest is historically relatively recent. At the turn of the twentieth century, with the rise of experts such as paediatricians, psychologists, psychoanalysts and professional pedagogues, children began to be regarded as vulnerable, sensitive to social and educational pressure. ‘Stress’ became a legitimate complaint, and parents began to worry about the future psychological consequences for their children of their current disciplinary actions and educational practices.

The notion that children should be kept happy and entertained and that childhood should be a valuable time in itself grew significantly (helped by the entertainment industry). As a result, educationalists and parents began to worry about school pressure, homework, and overloading children with work.

At the same time, the twentieth century witnessed (in the Anglo-Saxon world) the rise of an educational discourse centred on parental responsibility, making it clear to parents that they were holding the future of their children in their hands. This was accompanied by the increasing marketisation of education and the ideology of parental choice: the notion that parents should decide which education to give their children, should get involved in schools, and the implicit encouragement to do so actively, ‘empowering’ themselves and their child through educational consumption.

A third important variable was the ever-increasing competitiveness at all levels of the educational system: between children, between schools, between countries, and between parents. There was a growing feeling that not everyone would succeed and that school years were crucial.

In this context, no wonder the construct of child ‘giftedness’ became so appealing and so uncomfortable, too. Children who are more precocious or apparently more ‘able’ than others elicit admiration and enthusiasm (and jealousy) because their current performance is assumed to be a good predictor of their adult achievements. At the same time, many people are deeply uncomfortable about ‘gifted’ children who (whether or not it’s ‘their choice’) spend most of their childhood ‘working’ on maths, music, writing, etc.

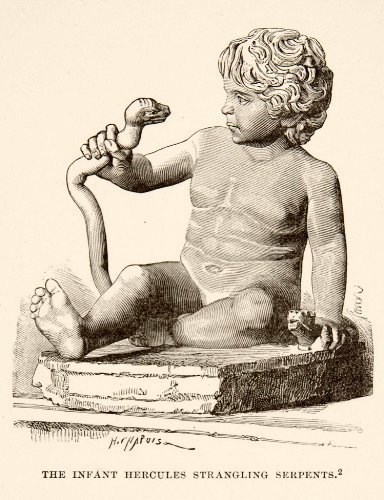

Our perception of highly ‘gifted’ children is never entirely positive: cautionary tales abound in the biographies of ‘geniuses’. OK, little Wolfgang Mozart did well professionally as an adult, but he was emotionally dependent, eternally childish and very depressed [this is much contested, by the way].

Happy Amadeus?

So… was it worth it?

Even when ‘gifted children’ have perfectly functioning lives as adults, many people argue that their childhoods were ‘unhappy’, ‘unnatural’ or ‘wrong’. Many of the angry responses to Amy Chua’s (quite hilarious) Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother revolved around a sense that she had killed everything that makes childhood childhood, and turned it solely into a preparation for adulthood (which she actually does not contest).

Since her daughters are now seemingly balanced, happy Harvard undergraduates, these attacks sound a little strange – yet they hint at people’s deep-seated beliefs that childhood shouldn’t be like that; that, again, you shouldn’t sacrifice a happy child, even for a future happy adult.

Currently, it is fair to say, the consensus among researchers seems to be that children identified as ‘gifted’ are not more likely than average to have mental health issues either in childhood or in adulthood (there is some evidence that they are in fact less likely to). Furthermore, unsurprisingly, children identified as ‘gifted’ tend to do better financially in future life than ‘normal’ children. Of course, these statistics shouldn’t obscure the fact that there are countless ‘gifted’ children with depression, anxiety, self-esteem issues, etc. There have been studies suggesting that they can are especially prone to insecurity and social maladjustment. But overall, ‘gifted’ children are doing pretty well on existing measures of ‘happiness’, emotional and psychological health and future prospects.

Perhaps we want to believe, in part because of our own blissful memories of days at the countryside, bedtime reading and just doing nothing, that there is an essential link between childhood and idleness, childhood and entertainment, childhood and a carefree spirit. But there is no such essential link.

We see ‘gifted’ children as ‘unnaturally’ preoccupied with work, with time, with preparation. Like we are now – like adults, only too early. By saying that they aren’t happy and won’t be happy in the future, because they work too much, because they’re constantly being told what to do, because they’re only preparing for the future – often without any definition of happiness - are we secretly complaining about our own current lives?

Or are we scared that they might overtake us too soon, and therefore reassure ourselves that at least, they won’t be happy?

There is disturbing glee, sometimes, in the prophetic claims that ‘gifted’ children are or will be unhappy. We secretly dream of them as tragic heroes, full of admirable hubris but necessarily struck down by fate.

Strangle all the serpents you like, baby Hercules – one day you will BURN TO DEATH (mwahaha)

And we shrug and say that academic success, financial comfort and social status have never brought happiness to anyone anyway…

So do we see these accelerated childhoods as painful symptoms, as annoying reminders, of the ruthless contemporary necessity to have returns on investments, to be competitive, to gain time? When we say they’re not happy, are we saying that we can’t be truly happy, only successful, if we play by the rules of this society we’ve made?

So much adult insecurity permeates those narratives of early successes.

Clémentine Beauvais's Blog

- Clémentine Beauvais's profile

- 301 followers