Think Like an Investor: Avoid Mistakes (and why you should play the loser’s game)

“An investor needs to make very few things right as long as he avoids big mistakes.”

–Warren Buffett

Charles Ellis wrote the now famous essay The Loser’s Game in 1946. In it, he compares sports — tennis in particular — to investing.

Ellis makes the distinction between a “loser’s game” and a “winner’s game”. In tennis it looks something like this. . .

Winner’s game

Played by professional tennis players.

The way to score — and win — is by hitting that special serve you’ve been working on for so long. Or by hitting that power shot that can only be used when the timing is perfect.

Loser’s game

Played by everyone who’s not a professional tennis player.

The way to score — and win — is by keeping the ball in play and not taking any unnecessary risks. Just focus on avoiding mistakes and you’ll be fine. Don’t give your opponent any easy points, for example by giving him the chance to smash.

These two styles rely on completely different strategies.

The winner’s game is about hitting fancy moves, mastering timing, outsmarting your opponent and taking risks.

The loser’s game is about sticking to fundamentals, avoiding mistakes and minimizing unnecessary risks.

However, investing is more complicated than sports. Success in life is also more complex (and less predictable) than sports are. . .

. . . But the analogy still holds true.

So, which of these two strategies is it most important that you use in your own life?

You guessed it: The loser’s game.

Even if it’s tempting to play the winner’s game, you should only play it in those rare circumstances when you’re actually the pro. Usually you’re not the pro.

Yet most people think they are.

–And so, they end up doing stupid things because they overestimate their own skill or intelligence. They suffer from inflated egos.

To be able to outperform the market you must be able to outthink the consensus. Are you capable of doing so? What makes you think so?

–Howard Marks, The Most Important Thing Illuminated: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor (Columbia Business School Publishing)

The Most Important Thing

If you’re going to outthink the consensus you have to be above average — and that doesn’t just go for investing. That goes for anything.

There have been all sorts of research on this, and the general conclusion is that: Most people think they’re above average at just about everything.

There’s a famous study done in Sweden (of all places!) that asked people whether they believed they were better than average at driving. What were the results?

About 90 % of the people asked believed they were better than average drivers.

Obviously this cannot be true, as only 49 % of people can be above average. This cognitive bias of overestimating your own abilities is sometimes called excessive self-regard tendency.

Then there was a test that was done twice, first in 1945 and then in 2003. It asked “are you an important person?” In the first instance 2 out of 10 respondents answered “Yes, I’m an important person”. The second time, in 2003, 6 out of 10 respondents answered the same. The evidence is in. . .

. . . We live in a society with a lot of ego-deluded people.

There’s a saying in poker, I’m sure you’ve heard it:

If you can’t spot the sucker at the table, then guess what? You’re the sucker.

In life, whenever you cannot spot the sucker you should assume you’re it, and:

Hold on dearly to your money and get out of there ASAP, or

Play for fun and set a clear limit to your commitment of resources and when you’ll quit (like a rich guy in Vegas)

If you must play, you should play the loser’s game (and avoid mistakes)

Yet, because of excessive self-regard tendency, most people won’t do any of these things. They’ll play the winner’s game instead.

This is because think they’re better than they really are, even though they don’t have any solid experience to base that belief on.

I know what you’re thinking:

How can they be so incompetent?

– Because the more incompetent someone is, the less likely they are to realize how incompetent they are.

And vice versa: The more you know, the more likely you are to realize how much more there is to know, or how limited your knowledge on a topic is. Intelligent people know their limitations.

Overestimating what you’re capable of knowing or doing can be extremely dangerous–in brain surgery, trans-ocean racing or investing.

–Howard Marks, The Most Important Thing Illuminated: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor (Columbia Business School Publishing)

The Most Important Thing

You should only play the winner’s game when you can easily spot the sucker.

However. . .

Not All Pros Play the Winner’s Game

Not even in professional sports:

Ted Williams is the only baseball player who had a .400 single-season hitting record in the last seven decades. In the Science of Hitting, he explained his technique. He divided the strike zone into seventy-seven cells, each representing the size of a baseball. He would insist on swinging only at balls in his ‘best’ cells, even at the risk of striking out, because reaching for the ‘worst’ spots would seriously reduce his chances of success.

And some of the best investors — Like Warren Buffett — don’t do it either:

As a securities investor, you can watch all sorts of business propositions in the form of security prices thrown at you all the time. For the most part, you don’t have to do a thing other than be amused. Once in a while, you will find a ‘fat pitch’ that is slow, straight, and right in the middle of your sweet spot. Then you swing hard. This way, no matter what natural ability you start with, you will substantially increase your hitting average. One common problem for investors is that they tend to swing too often.

–Peter Bevelin, Seeking Wisdom: From Darwin to Munger, 3rd Edition

Seeking Wisdom

According to Ellis, here’s what you must do to win the loser’s game:

For those who are determined to try to win the Loser’s Game, however, there are a few specific things they might consider. First, be sure you are playing your own game. Know your policies very well and play according to them all the time.

You have to stick to the system you have cleverly devised.

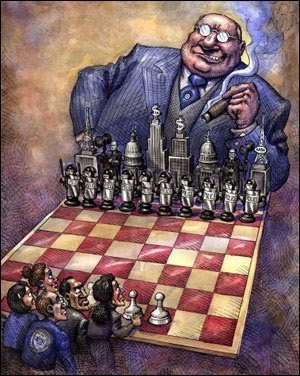

Otherwise you will get swept up in somebody else’s system.

Warren Buffett tells a story of how his mentor Benjamin Graham taught him to stick with what he knew best:

“He gave us a quiz,” Buffett said, “A true-false quiz. And there were all these guys who were very smart. He [Graham] told us ahead of time that half were true and half were false. There were 20 questions. Most of us got less than 10 right. If we’d marked every one true or every one false, we would have gotten 10 right.”

Graham made up the deceptively simple historical puzzler himself, Buffett explained. “It was to illustrate a point, that the smart fellow kind of rigs the game. It was 1968, when all this phony accounting was going on. You’d think you could profit from it by riding along on the coattails, but (the quiz) was to illustrate that if you tried to play the other guy’s game, it was not easy to do.

The moral of this story is. . .

. . . Don’t participate in competitions where you’re not the one making the rules.

It will leave you exposed to unnecessary mistakes.

Yet, lots of normal — non-professional — people believe they can outsmart the stock market and speculate over the short-term. What makes them think they can do this?

Do they have inside info?

Do they have a ton of capital?

Are they dealing with a business in an industry where they’re supremely knowledgeable?

–Nope.

They just think they’re smart. And when things — for some weird reason — go poorly and they lose their money, they blame it on bad luck.

They’re foolishly playing the winner’s game, and they’ll get slaughtered for it.

What they should do is to focus on. . .

. . . Avoiding Mistakes And Minimizing Stupidity

Because as Charlie Munger (Warren Buffett’s business partner and possibly the smartest man on the planet) says:

A lot of success in life and success in business comes from knowing what you really want to avoid — like early death and a bad marriage.

And. . .

It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently “not stupid”, instead of trying to be very intelligent.

If you want to be successful, and you have a long-term oriented outlook, there are some basic — yet very serious — things you want to stay the heck away from. You want to avoid things like:

Marrying the wrong partner

–By not settling for the first person who comes along.

Getting into business with a loser (someone that cannot be trusted)

–By checking their track record and judging their character accurately.

Getting addicted to (heavy) drugs

–By not doing them, obviously.

Getting fat and addicted to sugar

–By having a healthy diet.

Getting sick and unhealthy

–By working out and getting a good physique early in life.

Getting into debt

–By not buying things you don’t need, and never buying anything on credit (I’ve never understood how people can do this).

Associating with criminals and stupid people

–By not living in the ghetto, not hanging out where low-lives meet, or by politely ignoring them.

(What other things do you want to avoid in life?)

The point is for you to think of some worst-case scenarios and make sure that they NEVER happen.

When it comes to avoiding mistakes and minimizing stupidity, your best strategy is prevention.

“What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end.”

The best practical method for prevention is to. . .

. . .Figure Out the Root Cause And Solve it!

Have you got a problem?

General problems — the type that happen often — are the ones that it’s most important you solve.

But first you have to find the problem and know when it happens.

There are two smart ways to FIND general problems:

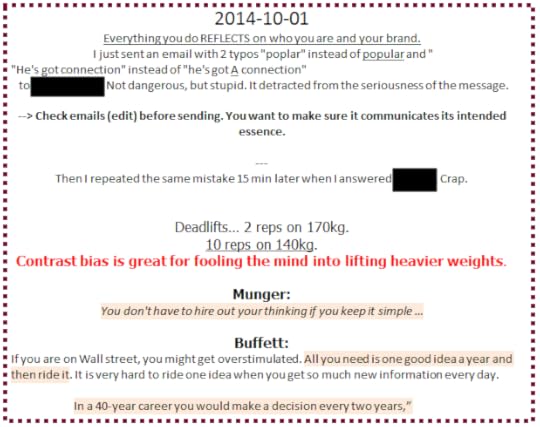

Write down daily lessons (make a section in your commonplace)

Ask “Why” five time

Daily lessons:

–You write down a few noteworthy things each day. Once a month (or at some other interval) you go through all the notes. Chances are you’ll find that you’re having a problem that’s happening over and over.

Here’s an example from my “daily lessons” section. Notice the bolded part in the top of the screenshot. That’s the solution.

Now I have to figure out the root cause and find a way to prevent it by. . .

. . . Asking “why?” x 5:

Example of mistake: “I sent an email with typos in it.”

Why?

–Because I was distracted.

Why?

–Because my concentration was weak.

Why?

–Because I was mentally fatigued from not having taken a break in over four hours.

Why?

–Because I thought I was being efficient.

Why [did you think you were being efficient]?

–Because I was putting in time.

Boom.

This misunderstanding — mistaking time for efficiency — is the root cause for the mistake. I will take more short restorative breaks to prevent it from happening again.

Sometimes you need to go even deeper and ask why more times. But usually five times is enough.

Why Smart People Do Dumb Things

Are stupid people the only ones who do dumb things or make big mistakes?

No.

Even some of the smartest people in the world make huge mistakes. Roger Lowenstein tells the cautionary tale of how the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management failed in his book When Genius Failed.

What is Long-Term Capital Management?

I’ll let Wikipedia answer that:

“LTCM was founded in 1994 by John W. Meriwether, the former vice-chairman and head of bond trading at Salomon Brothers. Members of LTCM’s board of directors included Myron S. Scholes and Robert C. Merton, who shared the 1997 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for a “new method to determine the value of derivatives“. Initially successful with annualized return of over 21% (after fees) in its first year, 43% in the second year and 41% in the third year, in 1998 it lost $4.6 billion in less than four months.“

In short: LTCM consisted of a group of incredibly intelligent people who all had brilliant track records. They made money by arbitraging (profiting on price differences) based on mathematical models. At one point, Institutional Investor called them “the best finance faculty in the world”.

Warren Buffett gives his take on how remarkable the failure of LTCM was:

The whole story of Long-Term Capital is fascinating. Because if you take Eric Rosefelt, Larry Hilibrand, Grek Hawkins, Victor Hagani, the two Nobel Prize winners: Merton and Scholes. . . If you take the 16 of them, they probably have as high an average IQ as any 16 people working together in one business in the country. Including at Microsoft, or whatever business you want to name. So you have an INCREDIBLE amount of intellect in that room.

Now, you combine that with the fact that those 16 had EXTENSIVE experience in the field they were operating. These were not a bunch of guys who’d made their money selling men’s clothing and all of a sudden got into the securities business. They had an aggregate of probably 350-400 years of experience doing exactly what they were doing.

And then you throw in the third factor — that most of them had nearly all of their very substantial net worths in the business. So, they had their own money up.

Hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars of their own money up, super high intellect, and working in a field they knew. . . And essentially, they went broke.

–So they had a lot of incentives acting in their favor, which should have motivated them to act intelligently.

But it didn’t.

And the underlying reason why they lost everything is because they. . .

. . . Risked what they needed to get what they did NOT need.

They wanted to make a little bit more money than they were already making. So they risked their reputations, their own money, and most importantly: The funds of their investors. . .

. . . And lost it all!

The potential profit was clearly NOT compensatory to the potential losses they might suffer.

But they went ahead and did it anyway.

And — Nobel Prize winner or not — if you risk something that is important to you, for something that is UNIMPORTANT to you, then you are a fool.

How to Make Fewer Stupid Mistakes in Life:

When you’re a pro — and you can clearly spot the suckers — you should play the winner’s game. It makes sense to take calculated risks and to use your fancy moves if the odds are in your favor. For example, when the game is rigged to your advantage.

When you’re not the pro — and you usually aren’t (!) — you should play the loser’s game. That means you want to stick to the fundamentals, avoid mistakes and minimize stupidity.

Key Strategies to Avoid Mistakes:

Figure out the root cause by asking why (x5) and solving the problem.

Figure out some worst-case scenarios in different areas of your life and make damn sure those things never happen.

Never risk what you have and NEED for what you don’t have and DON’T need.

Learn from the example of Long-Term Capital Management (ironic name, huh?). Even Nobel Prize winners make stupid mistakes — especially when they don’t stick to a set of core principles.

Photo credit:

The post Think Like an Investor: Avoid Mistakes (and why you should play the loser’s game) appeared first on Startgainingmomentum.