Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 7 – Plato – Part 1

Plato: The Rule of Reason

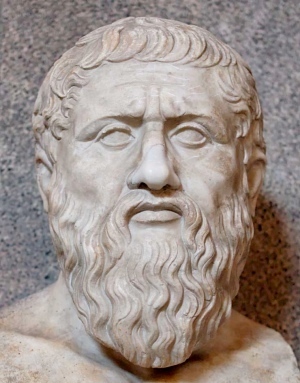

Plato (427-347 BCE) “was one of the first to argue that the systematic use of our reason can show us the best way to live.” [This is the implication for politics and ethics of the rise of reason in ancient Greece—the Greek miracle. It replaced superstitious, mythological, supernatural thinking with rational, philosophical, naturalistic thinking. Thus we are moving from ancient religious traditions to rationalism; to reason as the instrument for understanding ourselves. And the lives we live today owe much to the Greek miracle.] Plato argues that if we truly understand human nature we can find “individual happiness and social stability.” [We can answer ethical and political questions.]

Plato’s Life and Works – Plato “was born into an influential family … of Athens.” Athens was at the center of the Greek miracle, the use of reason to understand the world. He was especially influenced by Socrates, but after Athens lost the twenty-seven year Peloponnesian War with Sparta, Socrates came under suspicion and was eventually condemned to death. [You can read my detailed notes of the trial of Socrates as recounted in Plato’s Apology on canvas course site.]

Socrates was interested in political and ethical matters, especially about whether the Sophists were correct in defending moral (cultural) relativism. [This is the idea that morality is relative to, conditioned by, or dependent upon cultural conventions.] Socrates believed that the use of reason could resolve philosophical questions, especially if one employed the method of rational argument and counter-argument; the Socratic method of questions and answers designed to uncover the truth by engaging in a forum of rational discourse.

Socrates claimed that he did not know the answers to questions beforehand, but that he was wiser than others in knowing that he didn’t know. [This is the essence of Socratic wisdom—he is wiser than others in knowing he doesn’t know, whereas the ignorant often claim to know with great certainty. Through a series of questions and answers—the Socratic Method—he showed people they didn’t know what they claimed to know. Needless to say questioning people about their beliefs and implicitly asking them to defend them often arouses resentment and hostility. [Spinoza said “I cannot teach philosophy without being a disturber of the peace”]

Plato was shocked by Socrates execution, but maintained faith in rational inquiry. Plato wrote extensively, and in a series of dialogues, expounded the first (relatively) systematic philosophy of the Western world. [The early dialogues recount the trial and death of Socrates. Most of the rest of the Platonic dialogues portray Socrates questioning to those who think they know the meaning of justice (in the Republic), moderation (in the Charmides), courage (in the Laches), knowledge, (in the Theaetetus), virtue (in the Meno), piety (in the Euthophro) or love (in the Symposium).] The Republic is the most famous dialogue. It touches on many of the great philosophical issues including the best form of government, the best life to live, the nature of knowledge, as well as family, education, psychology and more. It also expounds Plato’s theory of human nature.

Metaphysical Background: The Forms - Plato is not a theist or polytheist, and he is certainly not a biblical theist. We he does talk of the divine he is referring to reason (logos) that organizes the world from preexisting matter. What is most distinctive about Plato’s philosophy is his theory of forms, although he is not precise as to what exactly this theory means. What Plato realizes though is that knowledge is an active process through which we organize and classify our perceptions. Forms are ideas or concepts which have at least 4 aspects:

A) Logical – how does “table” or “tree” apply to various tables/trees? How does a universal concept like “bed” or “dog” or “red” or “hot” apply to many individual things? [Any word except proper names and pronouns refers to a form] Nominalists argue that words simply name things, there are no universal concepts existing over and above individuals. [Words are convenient names that demarcate some things from others.] Platonic realists argue that universal forms really exist independently, and individual things are x’s because they participate in xness. [Dogs are mammals because they participate in doginess—which transcends individual dogs.] At times Plato suggests that there is a form for all general words–other times he doesn’t.

B) Metaphysical – are forms ultimately real, that is, do they exist independently? Plato says yes, universal, eternal, immaterial, unchanging forms are more real than individuals. Individual material things are known by the senses, whereas forms are known by the intellect. And the forms have a real, independent existence—there is a world of forms.

C) Epistemological – knowledge is of forms, perceptions in this world lead only to belief or opinion. We find the clearest example of knowledge based on forms in mathematics. [Hence the motto of Plato’s academy. “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here.”] The objects of mathematical reasoning are often not found in this world—and we can never see most of them—but they provide us with knowledge about the world. [Plato is challenging us to account for mathematical knowledge without positing mathematical forms. And even today most mathematicians are mathematical Platonists.]

D) Moral – ideals of human conduct, moral concepts like justice and equality are forms. [Plato has so far discussed physical, mathematical, and now moral forms.] Individuals and societies can participate in justice, liberty, or equality, but in this world we never encounter the perfect forms. The most prominent of all the forms is the form of the “good.”

The parables of the sun and cave are primarily about seeing the light of goodness. [Plato compares the suns illumination of the world with the form of the good’s illumination of reality.] Plato thought that thru the use of reason we could come to know the good … and then would do the good. Thus knowledge of the good is sufficient for virtue, doing the good. [This seems mistaken as Aristotle will point out because our will can be weak.] Thus Plato’s philosophy responds to intellectual and moral relativism—there are objective truths about the nature of reality and about human conduct. [The allegory of the cave, the myth of the sun, and the divided line are the devices Plato uses to explain the forms. I will explain these in tomorrow's post.]

Theory of Human Nature – The Tripartite Structure of the Soul – [Having encountered the social self of Confucianism, the divine self of Hinduism, and the no self of Buddhism, we come to dualism.]

Plato is a dualist; there is both immaterial mind (soul) and material body, and it is the soul that knows the forms. Plato believed the soul exists before birth and after death. [In our pre-existence our soul saw the moral and mathematical that it now remembers! We don’t see perfect circles or perfect justice in this world; we remember seeing them in Platonic heaven before we were born.] Thus he believed that the soul or mind attains knowledge of the forms, as opposed to the senses. Needless to say we should care about our soul rather than our body.

The soul (mind) itself is divided into 3 parts: reason; appetite (physical urges); and emotion/passion/ spirit/will. Examples of the latter include: love, anger, indignation, ambition, aggression, etc. There are thus 3 different aspects to our mental nature and when these aspects are not in harmony we experience mental conflict. Emotion or passion can be on the side of either reason or the appetites. We might be pulled by passionate love, lustful appetite, or the reasoned desire to find the best partner. Plato’s own image is of the charioteer (reason) who tries to you control horses representing emotions and appetites. [Elsewhere he says that reason uses the spirit (or will) to control the appetites. As the book says, the idea of emotion/passion/or spirit is. Nowadays we usually divide these as reason, appetite, and will.

Plato also emphasized the social aspect of human nature. We are not self-sufficient, we need others, and we benefit from our social interactions, from other persons talents, aptitudes, and their friendship.