Theories of Human Nature: Chapter 6 – Buddhism – Part 2

Buddhism: In The Footsteps of the Buddha

(I am teaching the course “Philosophy of the Human Person” at a local university. These are my notes from the primary text for the course, Twelve Theories of Human Nature.)

Diagnosis – We begin with the 4 noble truths. The first noble truth is that life is full of suffering and dissatisfaction. (This is also the third mark of existence.) We suffer from anxiety, insecurity, uncertainty, fear, frustration, disappointment and loss—everything is imperfect and flawed. In addition everything is constantly changing, radically impermanent, so even the good things and times never last. The first kind of suffering is ordinary suffering: aging, sickness, death, unpleasant conditions, sadness, pain, not getting what we want, etc. The second kind results from change, even happiness doesn’t last, is fleeting and ephemeral. The last type results from the false sense of ego. [Thus we suffer when slighted, insulted, not recognized, etc.] The Buddha did not say that life is essentially or only suffering but we experience much suffering. And this is not meant to be pessimistic but realistic—the basic problem of life is that we experience so much dissatisfaction.

The second noble truth identifies the cause of suffering as craving, grasping, desiring. We try to hold on to and possess things that don’t last. The essence of reality is change and grasping or desiring tries to prevent change by keeping things as they are. Much of this desiring is motivated by the idea of the separate ego, which wants to have more and more. [Think of it simply. I want money, sex, power, drugs, food, fame, etc. What happens? When in the state of wanting, I am dissatisfied. Then I get what I want, but soon I want more. I want a thousand dollars and then ten thousand and then a million and then a billion and I am still unhappy. The thrill of the new car or house makes me happy for a very short time. In fact studies show that after one has about a 100 thousand dollar income more money does not make people happier. Does a glass of wine taste good? Maybe. Do ten glasses make you feel better? Is it nice to have a roof over your head? Yes. Does having ten houses make your happier? No. This is what Buddha is getting at when he says our desires cause our troubles.]

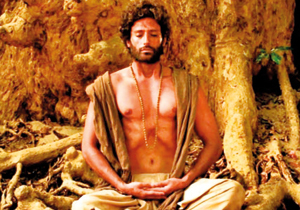

Prescription – The end of craving and desiring is the key to relieving suffering. This is the third noble truth. [This is of course antithetical to a capitalist economic system propelled by creating desires through advertising.] This leads to the state of nirvana, a peaceful state with no desiring. But what exactly do we do to experience this blissful state of not wanting and desiring and craving? We understand the fourth noble truth, which is to follow the eightfold path, also known as the Middle Way between a life of complete asceticism and a life of desiring pleasure. This path addresses ethical conduct, which is based on compassion, mental discipline, which flows from meditative practice and leads to the realization of the true nature of self, and wisdom, which is the realization of the true nature of reality.

Ethical components of the eightfold path include: 1) right speech—speech that tries to benefit others, speech that doesn’t lie, and silence when called for; 2) right action—moral, honorable, and peaceful conduct, no lying, killing, cheating, stealing, and the like; and 3) right livelihood—making a living without harming others. [Yes, the Koch brothers fail miserably on this one.]

Mental discipline is comprised of: 4) right effort—working toward wholesome rather than unwholesome states of mind; 5) right mindfulness—achieved through mindfulness meditation that leads to a better understanding of the impermanent nature of reality and lack of self; and 6) right concentration—meditation on a single point [like the breath, a flame, an image, a mantra].

Wisdom includes: 7) right thought—detachment from the idea of self; and 8) right understanding—accepting the 3 marks of existence (life is impermanent, there is no self, and there is suffering) and harmonizing the mind with this realization. It also implies accepting the 4 noble truths.

Different Paths – For monks this involves selfless, detached actions which aim to free one from karmic residue, and ultimately which leads to enlightenment. For the laity this involves doing good deeds, accepting the 5 precepts—don’t kill, steal, lie, consume intoxicant or have illicit sex—and improving their karmic lot. The monks provide a model of the spiritual life; the laity provides minimal food for the monks. In the Theravadan tradition the monk who reaches nirvana, while in the Mahayana tradition the bodhisattva does not enter nirvana but stays in this world and helps the rest of us be liberated. The bodhisattva is often characterized as more compassionate than the monk who withdraws from the world. In some schools of the Mahayana tradition the idea our true consciousness already exists and we must work to uncover it. [Similar to how Socrates thought of knowledge.] The idea is that we don’t have to work to achieve Buddha nature, but recognize that it is already within. [Even if it is within it seems we have to work to bring it forth.] The Mahayana tradition also recognizes other ways besides the monastic life to enlightenment, including devotional practices.

Women in Buddhism – In some texts woman are treated as inferior in Buddhism and perhaps by the Buddha himself; yet the Buddha allowed women to be monks as long as they were subordinate to men. On the other hand some Buddhist texts advocate an all-inclusive salvation. Today Buddhism is still dealing with these issues. [Obviously this is a controversial issue. However if you think this is only an issue in Hinduism or Buddhism consider what seminal Catholic thinkers like Augustine and Aquinas say about women:

“Woman is defective and misbegotten, for the active force in the male seed tends to the production of a perfect likeness in the masculine sex; while the production of woman comes from defect in the active force or from some material indisposition…” St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I q. 92 a. 1

“I don’t see what sort of help woman was created to provide man with, if one excludes the purpose of procreation. If woman was not given to man for help in bearing children, for what help could she be? To till the earth together? If help were needed for that, man would have been a better help for man. The same goes for comfort in solitude. How much more pleasure is it for life and conversation when two friends live together than when a man and a woman cohabitate?” St. Augustine, De genesi ad litteram, 9, 5-9

“Good order would have been wanting in the human family if some were not governed by others wiser than themselves. So by such a kind of subjection woman is naturally subject to man, because in man the discretion of reason predominates.” St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I q.92 a.1 reply 2

And you can find other disparaging remarks about woman throughout the history of philosophy. (Whatever you do, don’t read Schopenhauer!) I’d say the first thinker who says nice things about women is John Stuart Mill. For more see his book: The Subjection of Women (Dover Thrift Editions).