The Proverbial Thousand Words

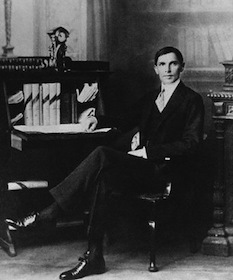

The current issue of Granta contains an enlightening Jane Perlez piece about Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), Pakistan's founding father. In making the argument that Jinnah's vision for the nation has been grossly misinterpreted, Perlez notes that it's easy enough to determine where a Pakistani official resides on the political spectrum. All you have to do is take a look at the portrait of Jinnah that hangs above his desk, as she did when visiting a friend at his Peshawar office:

The current issue of Granta contains an enlightening Jane Perlez piece about Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), Pakistan's founding father. In making the argument that Jinnah's vision for the nation has been grossly misinterpreted, Perlez notes that it's easy enough to determine where a Pakistani official resides on the political spectrum. All you have to do is take a look at the portrait of Jinnah that hangs above his desk, as she did when visiting a friend at his Peshawar office:

Government offices are important symbols in Pakistan—size, furniture, scope of retinue. This one was handsome, a large room set off a broad veranda in the ersatz Moghul-era quadrangle of pink stucco. A white mantelpiece signaled the dignity of the office holder. Above it hung a portrait, more a sketch in dingy brown, of Pakistan's founding father, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The face was gaunt and elderly—an aquiline nose, sunken cheeks, unforgiving mouth. A peaked cap high off his forehead and a plain coat buttoned to the neck gave the aura of a religious man…

A few months later I returned to see my friend. Same signing of documents, same clerk, different portrait above the mantel. The new visage showed a serious young man with a full head of dark hair, an Edwardian white shirt, black jacket and tie, alert dark eyes. What happened? I asked.

"I would like to see Jinnah brimming with life," my friend said. He did not want to be reminded of the clerical image that is now considered politically correct in many places throughout Pakistan.

This passage got me thinking about the ways in which visual representations of major political figures shape our perception of their intentions—often incorrectly, and by design of those in power. So much of a nation's identity is bound up in how we understand its mission statement, as crafted by the people who brought the enterprise together in the first place. But those founders were inevitably human, and their motives and ideals were often murkier than we'd care to admit. As Perlez points out in her piece, Jinnah never quite hashed out how the Islamists would be incorporated into Pakistan; he used their lingo to gain support for the nation's creation, but he didn't give enough thought to how they would mesh with his vision for a tolerant society. And he was far too quick to bargain away vast swaths of territory, without giving much thought to how those missing chunks would poison Pakistani politics down the road.

But we do not want our national heroes to be flawed figures. And so we depict them as full of confidence and valor—and, most important, as embodiments of the values that we've come to embrace in the decades or centuries since their passing. This may seem harmless enough, but the sad case of Pakistan must give us pause. Artists have warped Jinnah's visage to present us with a figure who bears little resemblance to the brilliant idealist who hoped that Pakistan might follow Turkey's lead in blending modern and traditional values. Or as Perlez puts it:

The Jihadistan that looms on the horizon as a the future of Pakistan, a likely compromise between extremist groups and the army, would not have a place for Jinnah today.

Can anyone think of other major political figures whose artistic representations now give us a skewed sense of their beliefs?