James Mc Intyre talks about Hessians and mercenaries of the 18th century

I’m so excited to have Jim here! We took a graduate-level class together, and teaches history for many undergraduates now. Actually, he taught back then too! He’s so talented, writing in his spare time an historical book I can’t wait to be released. Here’s some music to enjoy while you read through. And now help me welcome Jim!

What was so Significant about the Hessians? The Meaning of the Use of Mercenaries by the British in the American War of Independence

By

James R. Mc Intyre

It is impossible we should think of submission to a Government that has, with the most wanton barbarity and cruelty, burned our defenseless towns in the midst of winter, excited the savages to massacre our peaceful farmers, instigated our slaves to murder their masters, and is even now bringing foreign mercenaries to deluge our settlements with blood.[1]

These words, written by Benjamin Franklin to Lord Robert Howe in July of 1776 convey a powerful sentiment prevalent among American colonists concerning the British use of contract troops. Franklin continued, asserting that “These atrocious injuries have extinguished every spark of affection for that parent country we once held so dear.”[2] In his condemnation of British actions, Franklin built up to a crescendo of abuses the colonists had suffered at the hands of ministry. The proposed use of mercenaries by the Crown to subdue the revolt stood as the high note in Franklin’s scale. John Adams voiced a similar sentiment in a letter to James Warren earlier that same year. Adams claimed that George II “excluded the Inhabitants of these united colonies from the Protection of his Crown,” and, aided by foreign mercenaries, that the “whole Force of the Kingdom, is to be exerted for our Destruction.”[3]

These two well-known revolutionaries were not the only ones to decry the British government’s use of hired troops to suppress the insurrection of Britain’s thirteen seaboard colonies in North America. For instance, the New Hampshire House of Representatives noted, in June 1776,

the British Ministry, arbitrary and vindictive, are yet determined to reduce by fire and sword, our bleeding country to their own forces have engaged great numbers of foreign mercenaries…to ravage and plunder the sea coast; from all which we may expect the most dismal scenes of distress the ensuing year, unless we exert ourselves by every means and precaution possible.[4]

In like fashion, the members of the New York Convention, writing in July of 1776, attacked the actions of George III on this point in the following language,

He is, at this juncture, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to complete the works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. [5]

Clearly, many contemporaries viewed the use of foreign mercenaries as something of a dirty play on the part of the British government and more specifically, King George III.

Numerous historians picked-up on these contemporary perceptions and commented on the use of Hessian troops by the British ministry in putting down the American Rebellion. For Pauline Maier, “George III’s hiring of German soldiers to fight the colonists was cited almost everywhere and seems to have been decisive in alienating large numbers of colonists from the Crown.”[6] For Maier, the Ministry’s decision to employ mercenaries in the suppression of the colonial uprising served as a key factor in driving many to support independence. The following will address the question of the significance of the British employment of German mercenaries in the American War of Independence. Why did the use of mercenaries generate such a virulent reaction form colonists? Secondly, why did the use of German troops, in particular, exacerbate their anger? In order to answer these question, it is first necessary to examine the employment of mercenary by Great Britain troops in the European conflicts of the eighteenth century and how it was perceived. It will then discus the use of these troops in North America.

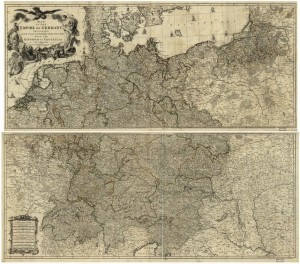

First and foremost, it must be pointed out that the designation mercenary served as something of a misnomer when applied to the troops raised by the British ministry. The troops raised by Great Britain in the German states of the Holy Roman Empire were more properly referred to as subsidy troops.[7] Therefore, the principalities of Anhalt-Zerbst, Hesse-Kassel, Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse Hanau, Waldeck, and Brunswick did not simply “sell” their troops to the British government.[8] Instead, they provided troops in return for monetary payment, but just as important, they received

Empire of Germany and its states

a treaty of alliance with Great Britain. This on its own constituted a valuable asset for smaller states squeezed in between larger, expansion-driven kingdoms such as Prussia and France. While they were still part of what historians refer to as the Soldatenhandel or “soldier trade,” the troops supplied by these six states were far from the traditional definition of mercenaries, soldiers who fought purely for financial gain. They were, in fact, serving the foreign policy of their monarch.[9] While the subsidy troops provided several benefits to their own prince, they allowed the Crown the opportunity to mobilize trained troops more rapidly than they could bring their own army, which was often under-strength in peacetime, to a wartime footing.[10]

It is worth noting as well that the American crisis was not the first time the British Crown turned to troops raised in the German states to augment their military forces. They had resorted to similar measures during the Jacobite Rising of 1745 led by Bonnie Prince Charlie.[11] In this case, the Crown had brought a contingent of Hessians over to Scotland to maintain security while British regulars completed the work of suppressing the rebellion. On this occasion, the use of subsidy troops received warm support from British popular opinion.

The preceding undoubtedly raises questions concerning the conduct of the Hessians in Scotland while pacification operations were taking place. Did these troops mistreat the civilian populace? The answer here is an unequivocal no. The eminent eighteenth century military historian Christopher Duffy explored this question in great depth. What he discovered, in fact, demonstrates quite the opposite. The Hessians were compassionate in their treatment of the Highland refugees in the aftermath of the battle of Culloden on April 16, 1746—the engagement that broke the back of the uprising. The restraint shown by the Hessians actually served to highlight the harsh nature of British policy. The hired troops behaved better towards a foreign population to which they had no connection than different members of the same kingdom.[12]

If the Hessians behaved with great restraint in Scotland some three decades previous, why was their proposed use in the American colonies so dreaded? The answer is twofold. First, many of the great thinkers of the Enlightenment possessed a decidedly negative view of the use of subsidy troops, equating it to slavery. As Peter H. Wilson observes, “It was not that the treaties themselves had changed, but rather the attitudes towards them.”[13] While this explanation serves to illuminate the negative reaction Britain’s use of various German contingents elicited in Europe, it sheds no light on the colonial reaction.

Ironically, a key to understanding the colonists’ reaction to the use of mercenaries may be the Scots. According to historian Frank Whitson Fetter, these were the mercenaries many colonists were referring to. Fetter notes that in a draft of the Declaration of Independence submitted for debate by Thomas Jefferson, he referred specifically to Highland Scots. These would be the descendants of many of those who fought at Culloden. In the aftermath of the uprsing, their chieftains had pledged loyalty to the British Crown, and they quickly became a bulwark of support for the government.[14]

The first Highland regiments were raised in the Seven Years’ War, and some saw service in North America. The 42nd regiment or Black Watch earned a particularly valorous record during their service in North America. For many at the time, Highlanders were considered semi-barbarous, and therefore a logical countermeasure in dealing with Native Americans.[15]

However, many ardent supporters of declaring independence were colonists of Lowland Scottish or Scots-Irish descent. A generic mention of “Scots” could potentially alienate them from the cause. Therefore, the designation of Scottish was removed, and generic mercenary remained. Generations have since assumed that the term referred specifically to the German troops then being raised in Europe by representatives of George III.[16]

So the Scots were the mercenaries feared by so many colonists on the eve of independence. They could be seen as mercenaries for the fact that their chieftains sold their support in return for their own political aggrandizement in the realm, or at least that was a hope. In this sense, as well, they  would fit into the growing debate on slavery and human rights. As previously noted, this debate occurred across the Atlantic World, and numerous groups could be categorized as slaves, whether they were Africans toiling in the Caribbean or North Carolina, Hessian subsidy troops, or Scottish clansmen.[17] As Charles Royster notes, the opposition to slavery constituted a powerful motivation for taking up arms against the British Ministry, for “If a generation enslaved itself, it enslaved its posterity, who would never know a different state.” [18] Thus, the vitriolic response to the use of mercenaries sprung from their potential for enslavement of a free people.

would fit into the growing debate on slavery and human rights. As previously noted, this debate occurred across the Atlantic World, and numerous groups could be categorized as slaves, whether they were Africans toiling in the Caribbean or North Carolina, Hessian subsidy troops, or Scottish clansmen.[17] As Charles Royster notes, the opposition to slavery constituted a powerful motivation for taking up arms against the British Ministry, for “If a generation enslaved itself, it enslaved its posterity, who would never know a different state.” [18] Thus, the vitriolic response to the use of mercenaries sprung from their potential for enslavement of a free people.

[1] Benjamin Franklin to Lord Howe, July 21, 1776, quoted in American Archives, Series 5,volume 1, 482-83.

[2] Ibid.

[3] John Adams to James Warren, May 15, 1776, quoted in Letter of the Delegates of the Continental Congress, vol. 3, January 1-May 15, 1776, 678.

[4] Minutes: New Hampshire House of Representatives, June 14, 1776, quoted in Am. Arch., Series 5, vol. 1, 66.

[5] New York Convention quoted in Ibid, 1389.

[6] Pauline Maier, American Scripture, 80.

[7] Several historians have done extensive research in this area. They include Charles W. Ingrao, The Hessian Mercenary State: Ideas, Institutions, and Reform under Frederick II, 1760-1785. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

[8] The two main works to address the use of Hessian auxiliaries by the British in the War of Independence are Edward J. Lowell The Hessians and Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War. Gansevoort, NY: Corner House Historical Publications, 1997 reprint of 1927 original. More recent, though still dated is Rodney Atwood The Hessians: Mercenaries from Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

[9] On the Soldtenhandel, see Peter H. Wilson War, State and Society in Wurttemberg, 1677-1793. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, 174-78. For a discussion of how the use of subsidy troops effected the policy of Hesse Kassel in particular, see Ingrao The Hessian Mercenary State, 122-163.

[10] On the benefit to the British government, see Atwood, Hessians, 15. For the state of the British Army in peacetime, see J.A. Houlding, Fit for Service The Training of the British Army, 1715-1795.Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981, 11-13.

[11] Christopher Duffy The ’45: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Untold Story of the Jacobite Rising. London: Cassell Military, 2003, W.A. Speck The Butcher: The Duke of Cumberland and the Suppression of the ’45. Caernarfon: Welsh Academic Press, 1995, and A.J. Youngson The Prince and the Pretender: Two Views of the ’45. Edinburgh: Mercat Press, 1996.

[12] Christopher Duffy, The Best of Enemies: Germans against Jacobites, 1746. Chicago, IL: the Emperor’s Press, 2013, 132-33. For an excellent discussion of restraint versus atrocity in several different but contemporary contexts, see Wayne E. Lee, Barbarians and Brothers: Anglo-American Warfare, 1500-1865. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Unfortunately, Lee does not discuss the Jacobite Rebellion.

[13] See Wilson War, State and Society, 75.

[14] Frank Whitson Fetter “Who Were the Foreign Mercenaries of the Declaration of Independence?” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 104, 4(Oct. 1980) 508-13.

[15] On the Highland units used in American in the French and Indian War, see Stephen Brumwell, Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1775-1763. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, 164-189.

[16] Fetter, “Who Were the Foreign Mercenaries,” 509.

[17] For a thorough discussion of the concept of the Atlantic World and the changing place of slavery in it, see Aaron Fogleman, “The Transformation of the Atlantic World, 1776-1867.” in Atlantic Studies, 6, 1 (April 2009): 5-28.

[18] Royster, Revolutionary People at War, 7.