Advice about writing can be good or bad so how can you tell the difference?

Today is the one year anniversary of the Insecure Writer's Support Group website. To celebrate, the insecure writers of the world are putting together an anthology. The book's purpose is to assist and encourage other writers on the journey, so they are looking for tips and instruction in the areas of writing, publishing, and marketing. Now, since there is so much of this on the internet already, and I think there is literally nothing I can say that can add to this chorus, I thought I'd write an article on decision-making itself and how a person can separate good advice from bad advice. To be clear, my article here isn't intended for the anthology. Rather it's meant to somehow complement all the advice that's out there by perhaps looking at the giving and receiving of advice in a different light.

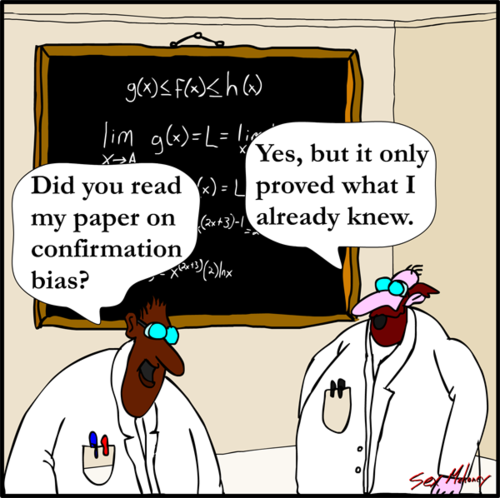

Today is the one year anniversary of the Insecure Writer's Support Group website. To celebrate, the insecure writers of the world are putting together an anthology. The book's purpose is to assist and encourage other writers on the journey, so they are looking for tips and instruction in the areas of writing, publishing, and marketing. Now, since there is so much of this on the internet already, and I think there is literally nothing I can say that can add to this chorus, I thought I'd write an article on decision-making itself and how a person can separate good advice from bad advice. To be clear, my article here isn't intended for the anthology. Rather it's meant to somehow complement all the advice that's out there by perhaps looking at the giving and receiving of advice in a different light.In the realm of "advice" I think the word "specious" comes to my mind particularly often. The definition of "specious" is something that has the "ring of truth" but is inherently false, and it's been my observation that all of us are guilty of accepting specious advice because of a thing called "confirmation bias."

Now, if you don't know what this is, "confirmation bias" happens in those moments where everything you see seems to confirm your wisdom. It occurs because of a misconception that your opinions are the result of years of rational, objective analysis when in truth...your opinions are the result of years of paying attention to information which confirmed what you believed while ignoring information which challenged your preconceived notions. Don't take my word for it, but take what Terry Pratchett has to say through his character Lord Vetinari from The Truth: a novel of Discworld:

Now, if you don't know what this is, "confirmation bias" happens in those moments where everything you see seems to confirm your wisdom. It occurs because of a misconception that your opinions are the result of years of rational, objective analysis when in truth...your opinions are the result of years of paying attention to information which confirmed what you believed while ignoring information which challenged your preconceived notions. Don't take my word for it, but take what Terry Pratchett has to say through his character Lord Vetinari from The Truth: a novel of Discworld:"Be careful. People like to be told what they already know. Remember that. They get uncomfortable when you tell them new things. New things...well, new things aren't what they expect. They like to know that, say, a dog will bite a man. That is what dogs do. They don't want to know that man bites a dog, because the world is not supposed to happen like that. In short, what people think they want is news, but what they really crave is olds...Not news but olds, telling people that what they think they already know is true."

So I guess if I have any advice to give with regard to accepting advice from others (writing or otherwise), it is this: be skeptical of anything that promises to solve a problem especially if it fits your existing ideology. Instead, consider examining the advice using a method outlined by Dr. Heidi Grant Halvorson in Psychology Today and see if it stands up to the following conditions/questions:

1) Is the advice true? Is there evidence that supports a conclusion?

2) Does the advice have actionable steps that can be reproduced by anyone? Take a recipe as an example. If you follow a recipe exactly, you will always end up with the same thing. If you apply this to say...publishing advice...and follow the steps someone has outlined exactly then you should be able to arrive at the same conclusion. If not, then the advice is probably bad.

3) Consider the source and what their agenda might be (if any).

Basically, what I'm saying is to be careful of taking advice that comes from such an ambiguous cloudy thing as "personal experience," especially if the personal experience is not framed properly. No two situations are ever alike, but with a proper frame job you can at least understand not just what worked but why it worked in the first place.

Published on October 01, 2014 06:01

No comments have been added yet.