Polyamorous Pacifists and Sentient Plant-monsters Collide in The Mirror Empire

In the world of Kameron Hurley’s The Mirror Empire, where magic users draw their power from one of three heavenly satellites, a dark star is rising, one whose ascendance heralds a time of cataclysmic change and war between realities. For Lilia, who crossed from one world to another in childhood, fleeing the wrath of an alternate, militaristic version of the peaceful Dhai culture she now inhabits, this means discovering her mother’s hidden legacy before it can destroy her. For Akhio, the younger brother and now unexpected heir of Dhai’s deceased leader, Oma’s rise brings politicking and treachery, both from Dhai’s traditional enemies and from within his own state. For Zezili, the half-blood daijian general of matriarchal Dorinah, charged by her alien empress with exterminating the nation’s daijian population, it means an uneasy alliance with women from another world; women whose plans are built on blood and genocide. For Rohinmey, a novice parajista who dreams of adventure, Oma brings the promise of escape – but at a more terrible cost than he could ever have imagined. And for Taigan, a genderfluid assassin and powerful omajista bound in service to the Patron of imperial Saiduan, it means watching cities burn as invading armies walk between worlds with the aim of destroying his. How many realities are there? Who can travel between them? And who will survive Oma’s rise?

The Mirror Empire hooked me in from the very first page.

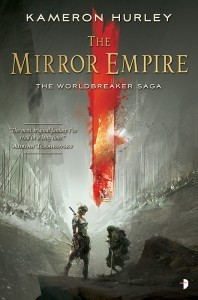

The Mirror Empire, the first volume of the Worldbreaker Saga, is Hugo Award-winning writer Kameron Hurley’s fourth novel, and from the minute I first saw the blurb, I knew I had to read it. The entire concept – backstabbing politics, polyamorous pacifists, violent matriarchs, sentient plant-monsters, doors between worlds – is basically my personal catnip, and when you throw in my enjoyment of Hurley’s first novel, God’s War, my expectations at the outset were understandably high. Which is ordinarily a risk factor: the more I invest in a story beforehand, the more likely I am to wind up disappointed. But The Mirror Empire, with its sprawling, fascinating mix of original cultures, political wrangling – both within the narrative and as cultural commentary – and vivid, brilliant worldbuilding, hooked me in from the very first page. The only reason it took me so long to read, in fact, was a personal reticence to have the story end: I’ve been drawing it out over weeks and months, prolonging the inevitable.

Though portal fantasies are undergoing something of a resurgence right now – hell, I’ve written one myself – there’s nothing predictable or typical about The Mirror Empire, and I mean that in the very best possible way. In this setting, invaders from a parallel reality are using blood-magic to push at the boundaries between worlds – but once a gate is open, the only way to cross from one reality to another is if your doppleganger on the other side is either dead, absent, or non-existent. Though the logic behind this conceit is never really explained – like much epic fantasy magic, it can ultimately be reduced to Because Reasons – Hurley explores the implications in fascinating ways, using her premise to underscore and inform the already unsettling and, at times, downright devious political machinations of her characters. There’s a reason the book has been described elsewhere as resembling the product of “an angry, feminist George R. R. Martin dropping acid and using steroids,” and violent political shenanigans is only part of it.

Art by Richard Anderson

It won’t come as a shock that Hurley is willing and able to write a broad spectrum of aggressive, complicated, narratively unconventional women with skill and nuance.

Which brings me to the book’s portrayal of women – and, more specifically, to the question of female violence. For anyone familiar with Hurley’s previous work, it won’t come as a shock that she is willing and able to write a broad spectrum of aggressive, complicated, narratively unconventional women with skill and nuance; what is nonetheless striking about her work, and particularly when viewed in a feminist context, is her penchant for writing about women as the perpetrators of both institutional and sexual violence against, not only each other and contextual outsiders, but men. And this is something I want to unpack, because one of the more luridly unsubtle genderflips of classic pulp SFF – and therefore of the collective geek unconsciousness – is the idea of, to mangle a phrase from Shakespeare, a bevy of bouncing Amazons, buskined mistresses and warrior-loves lording it over the lads, for which crime they are invariably situated as either a male sexual fantasy (strong women just want stronger men!) or the worst sort of radfem strawgirls (behold the misandrist, Dworkinite utopia!).

The idea being, of course, that female violence exists either to be fetishized by straight guys who still win out in the end, even if only sexually (“Death by snu-snu!”), or as a hypothetical, scaremongering perversion of “natural” womanly norms, the stereotype so deeply ingrained in culture that we rarely see it explored with any degree of intelligence or imagination, let alone empathy. What Hurley does, by contrast, is extend to women the same flawed humanity the rest of us customarily extend to men, bypassing the tired-yet-still-apparently-ubiquitous cliché that a country run by ladies would be inherently pacifistic in favour of treating women as people, which is to say, as persons as equally capable of bigotry, bias, ruthlessness, sexual aggression, violence and calumny as any other gender, and extending that thought to the creation of an entire culture. And thus the importance of Dorinah, whose matriarchy was founded (we can contextually infer) as a direct reaction to the historical oppressions of Saiduan, and of her general, Zezili – a character who would, in many ways, be archetypal if male, but who is nonetheless complex enough to defy being pigeonholed.

Art by Richard Anderson

Zezili has a pretty young husband, Anahva, whose actions are sharply constrained by the culture in which he lives – men wear binders to keep them weak, cannot travel alone, are married and sold as sexual ornaments – and, by our standards, does not treat him well, though she also (in her own way) cares deeply for him, if not always about him. Arguably, in fact, he is a victim of marital rape, and while we’re given this information in a way that doesn’t exonerate Zezili, we are still invited to view her as a complex character, one whose actions are dictated as much by her cultural upbringing as by her personal circumstances. Which is, in one sense, shocking; as much as I enjoyed her chapters, I was also deeply conflicted about my reactions to them. And yet the exact same narrative courtesy – that of offering absolution, or at least narrative sympathy, to the perpetrators of objectively horrific crimes – is routinely extended to popular male characters, such as, to press the Martin comparison, Jaime and Tyrion Lannister, whose acts of rape, abuse and murder are somehow never seen as reasons not to view them as interesting, or worthy of redemption.

Zezili, with her gruff, brutal affection for Anahva, her resentment at being ordered to commit an effective genocide against her own caste, and her competence, cleverness and complexity, is a direct challenge to everything that this forgive-men-their-sins mentality represents. Simultaneously, she forces us to ask ourselves, If I can sympathise with violent men, why can’t I sympathise with violent women? and, If I cannot sympathise with violent women, then why should I sympathise with violent men? This is the point and power of Zezili: she sits at the intersection of several of our strongest cultural biases, and therefore cannot help but press us to examine them. Are we too forgiving of violence generally, and of certain types of violence in particular? Or is it just that we’re too forgiving of men, regardless of what they’ve done? Either way, how should we strive to react to women who commit violence in stories – with acceptance and desensitisation, regardless of questions of gender? With a contextual awareness and comparison of gender roles both within the narrative and our own, real-world culture? Or with the revulsion we should arguably strive to feel for all such atrocities and those who commit them? Though many female characters in The Mirror Empire both commit and are subject to violence, it is Zezili who most thoroughly personifies these questions – and who, as a consequence, I cannot help but want to see more of.

Are we too forgiving of violence generally, and of certain types of violence in particular?

Nor is Zezili the only politically engaging character on offer – far from it, in fact. Though Hurley’s writing is not didactic, in the sense of forcing the protagonists to engage in endless philosophical debates (in the manner of, for instance, Terry Goodkind), she nonetheless manages to effect a powerful political commentary through a potent combination of worldbuilding, asides and gracenotes. Consider this early exchange, for instance:

‘I wonder,’ the sanisi said, ‘what does a pretty parajista with a fiery interest in death have to say to a plain-faced crippled girl?’

‘You have a weird way of seeing people,’ Roh said. ‘I don’t know why being plain matters. She’s very smart.’

‘I suppose when you don’t seek to own a thing,’ the sanisi said, ‘its beauty matters less.’

The Mirror Empire is full of such moments, some with more brevity than others, but all thought-provoking. But it is also, in the most imaginative sense, an original epic fantasy. The Dhai lands, where much of the action takes place, are home not only to one of many unique and richly described cultures, but a physical environment that feels like something out of the Final Fantasy franchise (and as an FF fan of many years’ standing, I mean that in the best possible way). And yet Hurley never overwhelms us with too many details: the mental pictures the story allows us to paint are creations of negative space, evoked through concept and language rather than infodumping, as per this example:

A great snuffling, crackling sound came from the forest. She poked her head above the poppies. Immense white bears with jagged black manes broke through the trees. Forked tongues lolled from their massive, fanged mouths. Their riders wore chitinous red and amber armour and carried green-glowing everpine branches as weapons, the sort imbued with Tira’s power. Lilia knew those weapons well – her mother used them to kill wolverines and walking trees.

Buy The Mirror Empire by Kameron Hurley: Book/eBook

The Mirror Empire is one of the best books I’ve read this year, and I cannot wait to see where the rest of series takes us.

In every sense of the word, therefore, and on every meaningful level, The Mirror Empire is a wholly ambitious novel – and overwhelmingly, it succeeds. Though there are times when the number of POV characters – or POV switches, rather – feels excessive, instances where the same information could have been conveyed more concisely or in a different way, in the end, any faults are minor compared to its virtues. It is exceedingly well-characterised, narratively gripping, compellingly worldbuilt, and politically powerful. Without a doubt, The Mirror Empire is one of the best books I’ve read this year, and I cannot wait to see where the rest of series takes us.

The post Polyamorous Pacifists and Sentient Plant-monsters Collide in The Mirror Empire appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.