Art of Reading, preamble

What are the possible relations between the field of artists’ books—one foot in the visual and plastic arts, one foot in the literary—and literature, especially, the notion of artful, imaginative reading as the center of literary life?

Many artists’ books, even despite whatever particular content or idea they pursue, will say something else: something about reading and about our relationships to books.

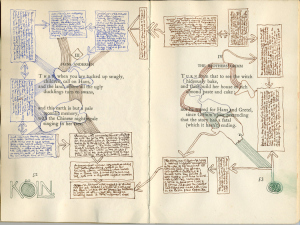

In the image above, by Tom Phillips, the visually dynamic annotations give dramatic form to what is always happening in our imaginations as we read. Phillips’s work is often lingering right at this boundary between the familiar tracings of reading that we associate with literary study / rich engagement in texts and the visual arts; but even highly visual / non-textual, and maybe especially, for me, sculptural books, do something similar.

I’ll be exploring this relationship between books as visual / sculptural form—as art objects in relation to the literary sensibility (be it nostalgia, fantasy, sense of knowledge or possibility, the monstrousness of texts, adoration and canonization of works by means of rich leather bindings, and so on) that we feel as an everyday phenomenon and as a quasi-mystical or existential connection, highlighted in the work of Mallarmé, Beckett, Blanchot, Borges, Jabes, and others.

A simply entry point is to compare a few images.

1.

The first gives us an image of the nostalgia for those affectionate moments of reading a paperback toward its destruction. Paperback novels show all their wear and tear as they crumble slowly in our hands. Reading destroys them, but first it marks them, folded back, shoved into a bag, dog eared, spilled on, dropped between mattress and wall, taken on the plane, etc.

2.

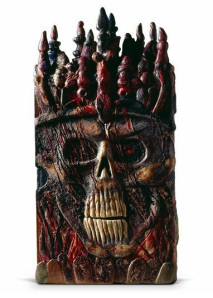

The second is, very likely, the same book, bound by Phillip Smith, a rich sculpture done in leather, sanctifying the ideas, adventures, and principally the magical exploits that take shape in our minds as we read fantasy adventure novels. On the one hand, Smith’s book would happily exist in Middle-Earth; on the other, it indulges in giving form to the imaginative experience of reading the text. There’s nothing sacred about a mass-produced adventure novel except that reading makes it so. It’s worth noting, of course, that Smith’s binding is probably not meant to be read; you wouldn’t take it on the bus with you. It is an object, a monument to reading and to imagination, and of course an homage to Tolkien’s work.

3.

Brian Dettmer’s “book autopsies” take us in yet another direction. As with Smith’s, book is again art-object more than functional-object, serving to represent something of our relation to books—not necessarily this particular book, but the ways that books transform, in our minds and memories, from rather flat, anesthetic experiences, into complex mental configurations, architectural spaces that might be wandered (the familiar text can be entered through any opening).

In these last two we have a potent relationship to reading without, in fact, touching or interacting with the reading process—a relation by referral, but without, we might say, engaging our reading muscles.

When do book artists do more than this? When do literary text and aesthetic object join forces to create new reading experiences? Many answers, both specific and generic offer themselves: everything from the collaborations of Stephen Farrell and Steve Tomasula to graphic novels / literary comics, the work of Susan Howe, Ann Carson’s Nox, and many artist’s books that play with significant narrative structures, especially the work of Johanna Drucker.

How do artists’ books and literary conceptions of the book as a significant formal container for language change our capacities to read?