Banned Books Month: Guest Post from E.K. Johnston: Missing the Catcher

Little, Brown and Company, Mass Market Edition, May 1991.

The history of banned books in my school board is pretty grim. Once upon a time, there had been a public meeting to ban Alice Munro’s LIVES OF GIRLS AND WOMEN. The CBC had shown up to film it, bringing some of the most recognizable names in Canadian culture to my small town, but despite Alice Munro’s defense of her work and the fact that Alice Munro was a local, the book was struck from the reading list.She has never come back to the building, as far as I know, and who can blame her?

So getting a book un-banned was kind of a big deal. We were all pretty thrilled. I mean, if it had been banned, it was probably exciting! And we were going to be the first class to read it. (Aside: the other profoundly exciting thing was that CATCHER was the first and only new book I ever had while I was in high school. Most of the others were from the 60s or 70s.) Anyway, we prepared for this momentous event by first studying FAHRENHEIT 451, for obvious reasons, and Mr. Y told us about JD Salinger and gave us the context for the work. This only served to heighten the anticipation, and so when our brand spanking new copies of CATCHER were handed out the day before Christmas break, we were all at fever pitch.

I read CATCHER IN THE RYE a few days after Christmas. I gave up a day of skiing, and skipped TOY STORY 2. I read the whole thing cover to cover.

And I was crushed.

I found it tedious. Boring. Obnoxious. Frustrating. I thought it was awful.

After the holiday, I found out that I was not the only person who felt that way. The whole class, or at least the ones who had done their homework, was similarly let down. We had thought that we were going to read something important. Something that was so devastatingly affecting that the school board had banned our older siblings from coming into contact with it. And instead, we’d been subjected to page after page of some whinging kid. It wasn’t until later in the spring, when the other two classes taught by Ms. B read the book and we started to talk with them about it, that I was finally able to put my finger on what was so anticlimactic about the whole experience.

The facts were these: It was 2001. Anti-heroes were nothing special. Being angry at your parents and teachers didn’t make you unique. Not having a clue what you wanted after high school or how to get it even if you did was run of the mill. Whatever it was that had made CATCHED IN THE RYE so scary to our parents’ generation was gone, long gone.

(I’ve since wondered if us being Canadian farm kids might have also had something to do with it, but that’s another discussion.)

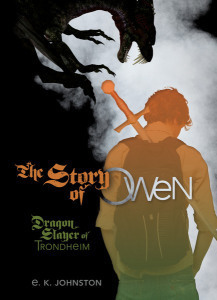

Carolrhoda LAB, March 2014.

I learned two lessons from CATCHER IN THE RYE, in the end. The first is that a person you admire very much might love a book and make you read it, and then you have to come up with a way to tell them that you rather felt like poking your eyes out with a spork the whole time you had it. The second is more applicable to the topic at hand.

Banning books is reactionary by nature, and the people who are doing the banning are very rarely the target audience of the book. Children and teenagers are much better at self-censoring and understanding things than they are given credit for. Banning a book might give them more of an impetus to read it (best case: they sneak into the public library every day for two weeks to read THE CLAN OF THE CAVE BEAR and then have to look up the sexy bits in Gray’s Anatomy because if they ask direct questions, they’ll be found out), but generally speaking, banning books serves only to make the banner appear short sighted (at the time) and woefully out of touch (when the book is finally reintroduced).

The key, as usual, is to read. Read, and then talk about what you’ve read. If you have an issue with a book, discuss it. Listen to some who disagrees with you on the matter, and then try to come to some sort of middle ground. Banning it outright, cutting off that conversation, stifles any development or forward movement. If boundaries never get pushed, then we all get very crowded. It’s not a very good place to be. How lucky for us that the solution is so simple.

E.K. Johnston.

Emily Kate Johnston is a forensic archaeologist by training, a bookseller by trade, and a grammarian by nature. Someday, she’s sure, she’s going to get the hang of this whole “real world” thing, but in the mean time she’s going to spend as much time in other worlds as she possibly can.

When she’s not on tumblr, she dreams of travel and Tolkien. Or writes books. It really depends on the weather. She lives in Ontario.

Visit her online at ekjohnston.ca.