The Pliocene Adventure -- Herbivores (Browsers) Part 2

Continued from Part 1.

Continued from Part 1.In a previous post I spoke of the difficulties with using the dates assigned to fossils in my database. Namely, that they are imprecise, so there is uncertainty as to when a creature actually lived. That got me to thinking about the issue all over again, and I came to two new realizations.

The first is that the ranges may be even more imprecise than I first thought. Aside from the problem of assigning dates based on stratigraphy and evolutionary descent, and the fact that the upper and lower limits given in the database are themselves averages based on collections of data points that represent a range of possible dates, there is the fact that many of them seem to be repetitive. That is, I saw a fair number of creatures with exactly the same age range: 4.9 to 1.8 mya. This just happens to correspond to the generally accepted age range of the Blancan faunal stage in North America. This made me realize that they were assigned this range, not because we know with any precision that they actually existed for that range of years, but because all the known fossils were excavated from Blancan deposits, and not from any that are older or younger. In other words, this date range doesn't mean a particular genus appeared 4.9 mya and went extinct 1.8 mya, but that it existed sometime during the Blancan, though exactly when we cannot say. The same is true for dates assigned to creatures still living today, except that to say a genus lived from 4.9 to 0.0 mya just means it first appeared sometime during the Blancan and has not yet gone extinct. This is especially true of creatures known from just a single type fossil, or perhaps a small collection, which is not enough to assign precise dates. So a range based on the faunal stage is a good way to hedge your bet, at least until more fossils are found.

My second new revelation was that the assigned date ranges can also be misleading. Many fossils in the database were found in deposits of the Irvingtonian faunal stage, which followed the Blancan and is assigned the range of 1.8 to 0.3 mya. It covered most of the Pleistocene, and along with the Rancholabrean stage that followed it featured the iconic "ice age" animals most people are familiar with. So, as with the Blancan fossils, the Irvingtonian fossils are generally given the same age range, 1.8-0.3, unless there is strong evidence for a more precise date. As I explained in a previous post, I rejected any genus that was younger than 3.3 mya, but what frustrated me was that many of the creatures that I wanted to include, like horses and camels and antelopes, were listed as living in the Pleistocene only. Which didn't make sense, because these were large families that included genera that lived before the Pliocene, and they lived nowhere else other than North America. So, if there were horses living 10 mya and 2 mya, but no fossils have been found from 5 mya, either they went extinct and then immigrated from somewhere else (which was impossible), or the fossils from the intervening years have just not yet been found.

However, I noted one curious feature of the database. For most fossils it lists what collections they belong to; that is, in what fossil beds they were found. These are listed by epoch or faunal stage, give the number of fossil beds excavated, and where those beds are located. For example, Sigmodon , the cotton rat, has been found in 188 beds throughout North America and places in Central and South America. Most of the beds contain Pleistocene deposits, so the genus is assigned a date range of 1.8-0.0 mya (it's still alive). However, 95 -- half -- of the beds are listed as being Blancan! So why is it given an upper limit of 1.8 mya? At first I thought that the people who maintain the database were hedging their bets; claiming that fossils could be Blancan because the cotton rat lived so close to that boundary. But then I took a closer look at the bed listed for Colorado, and I noticed that it had been assigned an age range of 4.9-1.8 mya; in other words, it contained Blancan deposits. Suddenly it dawned on me that the "official" date range for a genus might just represent the faunal stage that has the most specimens, or the range assigned to the first fossils collected before older ones were found (and intellectual inertia prevents the database from being updated in a timely manner). Regardless, what it meant for me was that it was evidence that some creatures lived before 1.8 mya, even if the database claims otherwise.

Now, this doesn't mean that these creatures lived 3.3 mya, but with all the uncertainties present in the dates, it no longer seemed important that the database had to show an exact date of 3.3 mya. Just stating it lived during the Blancan stage would be enough. I also learned that the database lists all the fossils collected from a particular bed, so I decided to go back and review all collections from all the Blancan beds in Colorado and the surrounding states of Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma, to look for creatures I had rejected because they were listed as living after 1.8 mya, but had still been found in Blancan deposits. I felt tempted to include Mexico, but in the end I decided not to since it was so far away, so my only Mexico-only creature will remain my rogue giant anteater.

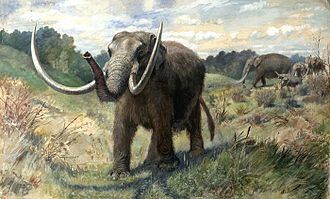

I didn't accept everything I found. Some creatures went extinct before 3.3 mya, and as long as I couldn't find any information that contradicted that, I accepted it as true. Others seemed too local, either because they were found nowhere else, or seemed too small to migrate very far, or seemed to be anomalies that I couldn't justify. For example, according to the database there were no mammoths in North America during the Pliocene, but one Blancan fossil bed in Oklahoma did yield up mammoth bones. Still, I decided not to include it because, being as no other Blancan mammoth fossils have been found, it felt too much like an anomaly to be trusted. However, I was able to fill out the ranks of my horses and camels with more genera, and I received a few surprises, not the least of which was the American cheetah. I had wanted to have something distinctly American in my list of animals, like the American lion or the sabre-tooth tiger, but they all lived too late, so having the cheetah is a real bonus.

Once again, the genus name for each creature is given in parentheses.

Mice -- The mice of the Pliocene are virtually no different from modern mice. They are one of the most numerous and diverse groups of mammals in existence, indicating an ability to adapt to almost any habitat, environment, and lifestyle. Though technically herbivorous, many tend to be omnivorous, eating worms, grubs, and insects, and at least one, the grasshopper mouse, is carnivorous, even eating small animals, including other mice (see the post on Insectivores).

(Baiomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the pygmy mouse because it has some of the smallest species on record. It prefers grassland and open savannas.

(Bensonomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Benson's mouse"

(Calomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the vesper mouse because it mostly comes out in the evening. It prefers savanna and scrubland.

(Guildayomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Guilday's mouse"

(Hibbardomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Hibbard's mouse"

(Loupomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Loup's mouse"

(Nebraskomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Nebraska mouse"

(Perognathus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the pocket mouse because they have large cheek pouches in which to transport seeds. It prefers arid grassland.

(Peromyscus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the deer mouse because they are accomplished runners and jumpers. They prefer wooded areas.

(Pliozapus) -- This Genus is extinct. "Pliocene jumping mouse"

(Reithrodontomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the harvest mouse because they are frequently seen feeding on crops ready to be harvested. It prefers well-watered grassland.

(Symmetrodontomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Symmetrical-toothed mouse"

(Zapus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the jumping mouse because it resembles a kangaroo rat in body shape and is a prodigious jumper. They prefer meadows and forests.

The Denver plain is filled with mice, which serve as the basis for many food chains. Though Kitty is an important member of the team in any event, if all she did was catch mice who invade the cave her presence would be most welcome. TG & Differel are not frightened of mice, but aside from getting into their food, clothing, and other supplies, they pose a health hazard by exposing them to Pliocene diseases.

Muskrat (Ondatra) -- This is the contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. They live in wetland habitats, including rivers and ponds. They do not alter their environment as beavers do, but they can have an impact on the kinds of vegetation that grow in their domains. They also maintain open areas in marshes, which benefit many other kinds of animals. Though they can steal food from Beavers, they can also form cooperative partnerships. In places where they build mounds of vegetation called push-ups to live in, large herbivores can feed on them when no other food source is available.

Muskrats are plentiful on the Denver plain. Mostly they live in the rivers, but they also live in the lake-ponds of the giant beavers, whose shallow areas form marshes that the muskrats preserve and expand. A family also lives in the beaver pond below the cave, and TG & Differel observe them working with the beavers to maintain the ponds and keep the nearest of the lower ponds open. They kill and eat muskrat on occasion, and Sunny experiments with making clothing from their fur.

Peccary -- These are a subgroup of wild pig-like animals. They are not ruminants like cows, but they have have complex stomachs with three chambers, allowing them to digest course vegetation like grasses. Even so, they are omnivores and will also eat roots, seeds, nuts, fruits, and small animals. They live in herds, and they can be aggressive towards predators. They can occupy a wide range of habitats, from arid scrubland to tropical rainforests.

(Catagonus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. Called the tagua, they prefer arid scrubland.

(Mylohyus) -- This Genus is extinct. It was slightly larger than modern peccaries and lived in open-canopy savanna and grassland.

(Platygonus) -- This Genus is extinct. This is the megafaunal variety of this animal, growing to 3 feet long. It also had longer legs, indicating it was a good runner. It had a digestive system similar to a modern ruminant, suggesting it might have had a diet higher in cellulose than other peccaries.

(Tayassu) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. Called the white-lipped peccary, it can range anywhere from savanna to forest.

TG & Differel note that peccaries are fairly common on the Denver plain. They range from the scrubland at the base of the ridge west into the pine forests of the foothills, and north to south on the grassland and the open-canopy savanna, and in the closed-canopy woodlots. The megafaunal peccaries are the rarest, but whereas the other Genera occupy restricted territories, Platygonus goes wherever it will with impunity, except deep inside closed-canopy woodlots, where it would not have the room to fight or run. It is also more aggressive, probably because it is hunted by the largest predators, and it would rather fight than run.

In a major plot point, TG & Differel allow an injured big cat to seek refuge in the lower part of their cave. They decide to feed it until it can hunt again, and the first animals they target are a herd of Platygonus. Though they succeed in killing one, the rest of the herd attack them and force them to take refuge in a tree, which the herd tries to pull down. Sunny and Kitty have to come to their rescue, using another predator as an unwitting ally.

Porcupine (Erethizon) -- This is the contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. They prefer closed-canopy forests or open-canopy savannas, but they can adapt to a wide range of habitats, from desert to tundra. They prefer to rest in trees, but can create dens in rocky outcrops.

On the Denver plain, porcupines pretty much reside in the pine forests of the foothills of the Front Range, but individuals often follow river riparian zones or lines of open-canopy savanna deeper into region until they reach the grassland. They have not yet reached the ridge where TG/Differel have their cave. In fact, they won't even find out that porcupines exist until they encounter a big cat with a quill in its paw. Later they will encounter them when they take trips west to investigate the foothills.

Rats -- Like mice, the rats of the Pliocene are virtually no different from modern rats, they are also a diverse group, and they too show an ability to adapt to almost any habitat, environment, and lifestyle. However, the rats of the New World belong to a different family from the true rats of the Old World, which would not reach the Americas until the middle of the second millennium AD.

(Neotoma) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the woodrat because it is typically found in forests; however, it can adapt to a wide range of habitats, including deserts and rocky treeless environments. It is also called a pack rat because of its habit of collecting "treasures" and storing them in its nest.

(Repomys) -- This Genus is extinct.

(Sigmodon) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the cotton rat because it makes its nest out of cotton. It can be found in a wide variety of environments, but prefers grassy areas with shrubs, regardless of environment. It is more omnivorous than the other two Genera, and occasionally eat insects and other small animals.

Unlike mice, rats on the Denver plain confine themselves to their preferred habitats and do not range far beyond. They are also more wary, and try to avoid TG & Differel rather than investigate their equipment and supplies. Kitty considers them a welcome change from mice and ground squirrels.

Sloths, Ground -- These Genera are extinct. Aside from the mammoth and perhaps the sabre-toothed tiger, people would be hard-pressed to imagine any mammal more quintessentially prehistoric than the ground sloth. This was a diverse and extremely successful group that lived for 35 million years and only became extinct as little as 11,000 years ago. Though not all were giants, or even strictly ground-dwelling, their great size and weight, thick skin, and highly developed claws made them nearly invulnerable to even the largest most powerful predators. The only thing more impressive than seeing them stride majestically across the plains would be a herd of mammoths.

(Megalonyx) -- It was 8-10 feet long and weighed over a ton, and that was medium-sized for a ground sloth. It ate tree leaves and branches, suggesting it preferred open-canopy savannas to forests, but it may have dug for tubers as well, and even ate meat on rare occasions. It could stand erect on its hind feet and stout tail.

(Paramylodon) -- It was 10 feet long and weighed a ton. It could stand erect and it preferred more open spaces to forage for grass and tubers, but with access to trees to feed on leaves and branches.

Tg & Differel were disappointed that there were no mammoths in mid-Pliocene Colorado; at least, not near Denver. But the ground sloths made up for it. In a minor plot point, TG/Differel allowed their enthusiasm to get the better of them, and they got too close to a young Paramylodon, which attacked them. Though not harmed, it trapped them and Kitty had to distract it so they could get away.

Squirrels, Ground -- These are contemporary Genera, and their Pliocene species are virtually identical to the modern species. For all intents and purposes they live and behave like chipmunks or smaller versions of marmots.

(Ammospermophilus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. They are called antelope squirrels because their markings and fur color are reminiscent of African antelopes. They prefer rocky habitats with dry sandy soil and shrubs. They are omnivorous, eating insects, small animals, and carrion as well as foliage and seeds. They live in colonies and have been known to mob smaller predators such as snakes, even killing and eating them.

(Spermophilus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. However, it is no longer native to North America. It prefers grasslands with dry soil. It forms colonies for protection. It eats grass, foliage, flowers, seeds, insects, bird eggs, and sometimes chicks.

As far as TG & Differel are concerned, these small ground squirrels are nearly as bad as mice when it comes to invading their cave, for much the same reasons, though only the antelope squirrels are a nuisance because they live on the ridge. Though Kitty keeps them at bay, their tendency to mob predators means they can seriously injure her if she attacked a colony.

Tapir (Tapirus) -- This is one contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. Tapirs are large animals shaped like pigs, but with short prehensile snouts. Though they live in forests or open woodland, they prefer to reside next to water, because they spend a great deal of time in and under the water to feed, hide from predators, and cool off. They also like to wallow in mud pits. They eat leaves, shrubs, aquatic plants, fruits, and seeds.

The tapirs living on the Denver plain reside in the riparian zones along the rivers rather than the beaver ponds, because the latter do not have enough trees and shrubs to feed or protect them. They are vulnerable only to the larger predators, most of which do not hunt in the closed-canopy woodlots, but the tapirs sometimes venture out onto the grassland to feed on ground plants.

Voles -- These are small mouse-like rodents, but with significant anatomical differences. They live a similar lifestyle and occupy similar habitats. However, while they can eat seeds, nuts, fruits, insects, even carrion, they prefer small plants, roots, and bulbs. Like mice, they serve as the basis for many food chains.

(Lemmiscus) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the sagebrush vole because it lives in open brushy areas such as sagebrush lots. It resembles the lemming.

(Mimomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the water vole because it lives near water and often goes swimming. It is the largest vole in North America, often growing to 10 inches in length.

(Ogmodontomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Furrow-toothed mouse"

(Phenacomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the heather vole because it lives in habitats with heather plants.

(Pliophenacomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Pliocene heather vole"

TG & Differel don't have nearly as much trouble with voles as they do mice, because the voles do not live near them. In fact, they won't even know they exist until they trap some.

Published on September 08, 2014 03:53

•

Tags:

animals, browsers, herbivores, pliocene

No comments have been added yet.

Songs of the Seanchaí

Musings on my stories, the background of my stories, writing, and the world in general.

- Kevin L. O'Brien's profile

- 23 followers