Lessons for Calgary from a failed, body-less murder prosecution

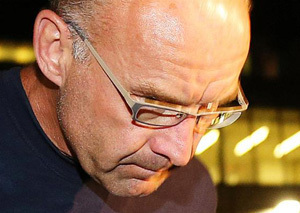

There is a name – Robert Baltovich – that Calgary Police homicide investigators likely are loath to consider as they hunt the bodies of three murder victims. Baltovich (inset) is a member of an exclusive club in Canadian criminal history: a man convicted of murder in the absence of the body of a victim, who was later was exonerated. Baltovich was convicted of second-degree murder in 1992, although police had not found the body of his purported victim, his girlfriend Elizabeth Bain. The 22-year-old Toronto woman disappeared in 1990. Baltovich spent eight years in prison. In 2008, he was acquitted after a second trial. Baltovich is suing, claiming malicious prosecution, in a case that soon will pass the quarter century mark and that exemplifies the difficulties of a prosecution in which authorities lack a critical piece of evidence, the body of the victim. Elizabeth Bain’s remains have never been found. In Calgary, nearly two months have elapsed since the disappearance of Alvin Liknes, 66, his wife Kathryn, 53, and their five-year-old grandson Nathan O’Brien. Police have said that their bodies have not been found. Despite this, investigators concluded that the three were murdered. Douglas Garland, a 54-year-old man with business and personal ties to the victims and a criminal record, has been charged with the murders.

There is a name – Robert Baltovich – that Calgary Police homicide investigators likely are loath to consider as they hunt the bodies of three murder victims. Baltovich (inset) is a member of an exclusive club in Canadian criminal history: a man convicted of murder in the absence of the body of a victim, who was later was exonerated. Baltovich was convicted of second-degree murder in 1992, although police had not found the body of his purported victim, his girlfriend Elizabeth Bain. The 22-year-old Toronto woman disappeared in 1990. Baltovich spent eight years in prison. In 2008, he was acquitted after a second trial. Baltovich is suing, claiming malicious prosecution, in a case that soon will pass the quarter century mark and that exemplifies the difficulties of a prosecution in which authorities lack a critical piece of evidence, the body of the victim. Elizabeth Bain’s remains have never been found. In Calgary, nearly two months have elapsed since the disappearance of Alvin Liknes, 66, his wife Kathryn, 53, and their five-year-old grandson Nathan O’Brien. Police have said that their bodies have not been found. Despite this, investigators concluded that the three were murdered. Douglas Garland, a 54-year-old man with business and personal ties to the victims and a criminal record, has been charged with the murders.

The victims, (from left) Alvin Liknes, Kathryn Liknes, Nathan O'Brien

Two weeks after the disappearances, Garland was charged with two counts of first-degree murder related to the Likneses and one count of second-degree murder for Nathan, an indication that investigators believe the boy’s killing was not intentional. Despite what Calgary’s police chief described as an “immense investigation” conducted by a small army of 200 officers, investigators, analysts, forensic experts and others, the bodies of the victims have not been located. At the news conference in mid July when police announced the charges, Chief Rick Hanson said investigators had reviewed 900 tips received in the first two weeks of the probe.

“The bodies of the three victims have not been found and we continue to ask people to come forward with any information they may have,” Hanson said. “Most importantly, we ask rural property and business owners to please search their properties for anything suspicious.”

Hanson did not say that investigators did not have any forensic evidence linked to the bodies of the victims so it is possible that police recovered fragments of tissue, fluids, clothing or other material that fuelled their conclusion that the three missing people were murdered. Any such findings could have helped investigators construct a timeline and determine where the victims were killed. Police have said that there were signs of a violent struggle inside the Liknes home in Calgary, where the three victims were last seen, that likely left one of the trio injured.

“We want to be able to find the bodies so that the family can have the final closure on this,” Hanson said, on July 14. Police have not given any indication, since that time, that they have located the bodies.

Douglas Garland is escorted to the Calgary Police processing unit on July 14, 2014 (photo: David Moll, Calgary Herald)

It isn’t impossible to convict a person of murder without a body. Peter Stark was convicted in 1994 of first-degree murder in the death of Julie Stanton, a 14-year-old girl who had been his neighbour in Pickering, Ontario. Julie disappeared in 1990. Her body was found two years after Stark had been convicted and sent to prison. In Stark’s appeal, the Court of Appeal for Ontario noted that at trial “there was no crime scene evidence placed before the jury, nor any other forensic evidence establishing a connection between [Stark] and Julie Stanton,” (emphasis added) yet Stark’s appeal was dismissed. In the only interview he’s given since his imprisonment, Stark told me, in a telephone conversation from Kingston Penitentiary in 1996, where he had begun serving his life sentence, that he was innocent. He remains behind bars.

In 1987, Al Dolejs, a Calgary man, was convicted of murdering his 12-year-old son Paul and his 10-year-old daughter Gabi. Their bodies were not found until after Dolejs was convicted, when he led police to the remains.

In a first-degree murder case the prosecution must establish, beyond a reasonable doubt, four essential elements: that the accused person committed an unlawful act, that the unlawful act caused the death of the victim, that the accused person had the intent required for murder and, the murder was both planned and deliberate.

In a case where there is no witness to the killing, Crown prosecutors must rely on circumstantial evidence to attempt to establish that the accused was with or near the victim in the place and at the time when it is most likely he or she was killed.

Without a body, the prosecution faces the unenviable task of establishing that the victim died and explaining the death – in this case the deaths of three people – without the best evidence. With a body, investigators often can determine the manner of death, that is, was the person shot, stabbed, strangled, bludgeoned or killed by some other means? A conclusion on manner of death sometimes points investigators to a murder weapon – a knife, gun or other instrument – something used to commit the crime that can be tied by forensics or other evidence to the accused.

Many murderers – because most aren’t professional assassins – use what they have at hand or what they can easily obtain to kill someone and to dispose of a body. In some cases, a killer is sloppy enough to use an item he owns or that is easily identified as belonging to him. In other cases, a murderer will purchase weapons or other implements that can later be tied to him, if found. Cop killers James Hutchison and Richard Ambrose purchased shovels at a hardware store, evidence that linked them to the freshly dug graves of the two police officers the pair murdered and buried near Moncton, New Brunswick.

Bodies often are repositories of evidence – hairs, fibres, fingerprints, DNA – that strongly link the accused to the corpse. Even if the body does not show clear evidence of physical contact with the murderer, it may offer evidence of a place – a location that might be tied to the murderer.

In the killing of Elizabeth Bain, police had none of these things. They did not have any forensic evidence that directly linked Baltovich to her murder. “The Crown’s case was entirely circumstantial,” Ontario’s top court noted, in a decision released in 2004 that paved the way for Baltovich’s exoneration. Because the Garland prosecution is at an early stage in the court process, it has not been revealed whether investigators have forensic evidence that links him to the victims. A murder prosecution built solely on circumstantial evidence isn’t necessarily weak. Juries at murder trials (most Canadian murder trials are conducted before juries) are told that they may infer facts from circumstantial evidence, such as records that establish a person’s location at a particular time, in the absence of direct evidence, such as the testimony of a witness who saw the accused at a location where the victim was found. In a case where the prosecution’s evidence is wholly or largely circumstantial, a judge also will caution jurors that they cannot convict the accused “unless you are satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that accused’s guilt is the only rational conclusion to be drawn from the whole of the evidence.”

In the Baltovich case, investigators and prosecutors could not establish with precision where, when or how Elizabeth Bain was murdered. Three days after she disappeared, her car was found, its seats stained with blood that matched Bain’s blood. The pattern of stains indicated that a body had been dragged into the car through the passenger door. At Baltovich’s trial, the prosecution laid out a theory: In a jealous rage on June 19, Baltovich killed his girlfriend, who was breaking off their relationship. He hid her body in the car for three days, then drove to a remote area 65 kilometres northeast of Toronto, where he disposed of her remains “in a place that to this day remains a mystery.”

Ultimately, Baltovich’s conviction was overturned primarily because the appeal court found that his trial was unfair. “The charge to the jury was unfair and unbalanced,” Ontario’s top court ruled. “It also contained significant errors of law that were prejudicial to the appellant.” The court ordered a new trial but at the second trial, the prosecution called no evidence and Baltovich was acquitted.

It is impossible to know what evidence investigators would have uncovered had Bain’s body been found soon after her disappearance. Since there was evidence she had been seriously injured (not unlike the finding at the Liknes home in Calgary), there might have been wounds on her body that pointed to a weapon, something tangible that could be tied to a killer. Finding Bain’s body would have cemented a timeline, narrowing the window of opportunity in which a perpetrator could have committed the murder and allowing investigators to zero in on particular individuals who had the opportunity to commit the crime during that period.

***

Though investigators may still be actively hunting the bodies of Alvin and Kathryn Liknes and Nathan O’Brien, those bodies would provide substantially less information if they are found now. If the three victims were killed and their bodies left outdoors, exposed to the elements, soon after they disappeared June 30, the remains would be primarily skeletal. We know this because of pioneering research done in the U.S. by forensic anthropologist Bill Bass. Bass and his researchers at the University of Tennessee developed a formula that charts the decomposition of a human body, based on surrounding temperature. A body is well on its way to skeletonization when it has an ADD (accumulated degree day) total of 800, which could be, for example, 10 days of 80 degree (fahrenheit) weather. The formula is applicable anywhere in the world. In Calgary in July, the average mean temperature for the month was 18 C (64 F), a figure that would produce an ADD of 1,984 (31 days X 64). The average mean for the first 24 days of August was 17 C (62 F), producing another 1,488 ADD. This is a total ADD of nearly 3,500, nearly three times the amount required for a body to skeletonize. Bass notes, in Beyond the Body Farm (HarperCollins 2007) that “by around 1,250 to 1,300 accumulated-degree-days, a body anywhere in the world would have been reduced to bare bone or bone covered with dry mummified tissue.”

***

Here’s the news briefing by Calgary Police Chief Rick Hanson, held July 14, 2014, at which he revealed that murder charges would be laid although, at the time, he would not identify Douglas Garland as the suspect:

Cancrime

- Rob Tripp's profile

- 8 followers