The Frankfurt School and the Proliferation of Alterity: Voices from the Right

[presented at the Alterity Conference, Genoa, Italy; July 2014]

– Michael McAnear, PhD*

National University

In 2010 the National Association of Scholars in the US analyzed what incoming freshmen are asked to read as part of college orientation programs prior to their starting school. Surveying 290 programs, the analyses concluded that “[. . .] the preponderance of reading assignments promotes liberal social causes and liberal sensibilities. Of the 180 books, 126 (70 percent) either explicitly promote a liberal political agenda or advance a liberal interpretation of events. By contrast, the study identifies only three books (less than 2 percent) that promote a conservative sensibility and none that promote conservative political causes." Common knowledge holds that the academy is dominated by the Left, and conservative commentators all over the West bemoan this fact. In Germany, for example, the leftist 68rs—so named to mark the cultural upheavals of the late sixties—are resented by some for their long standing dominance. Even in 1990, an editorialist for the right-of-center Die Welt was writing that “The ideology of the 68rs has settled like fine dust … into every nook and cranny of society.” As to the reading lists mentioned above, the president of the organization conducting the survey wrote that it supports these programs on American campuses but wants them out of "the rut of promoting trendy causes." Something is wrong when "books on Africa outnumber books on Europe nearly six to one,” (Jaschik).

In 2010 the National Association of Scholars in the US analyzed what incoming freshmen are asked to read as part of college orientation programs prior to their starting school. Surveying 290 programs, the analyses concluded that “[. . .] the preponderance of reading assignments promotes liberal social causes and liberal sensibilities. Of the 180 books, 126 (70 percent) either explicitly promote a liberal political agenda or advance a liberal interpretation of events. By contrast, the study identifies only three books (less than 2 percent) that promote a conservative sensibility and none that promote conservative political causes." Common knowledge holds that the academy is dominated by the Left, and conservative commentators all over the West bemoan this fact. In Germany, for example, the leftist 68rs—so named to mark the cultural upheavals of the late sixties—are resented by some for their long standing dominance. Even in 1990, an editorialist for the right-of-center Die Welt was writing that “The ideology of the 68rs has settled like fine dust … into every nook and cranny of society.” As to the reading lists mentioned above, the president of the organization conducting the survey wrote that it supports these programs on American campuses but wants them out of "the rut of promoting trendy causes." Something is wrong when "books on Africa outnumber books on Europe nearly six to one,” (Jaschik).

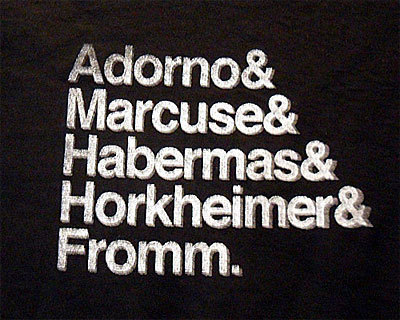

On the Right there is a compelling theory circulating to explain the Left’s dominance, a notion put forth not only in scholarly writings but of course spread on the Internet. The theory holds that the so-called Frankfurt School has exerted overwhelming influence in the West to shape cultural discourse in the academy, media, and society at large. This paper investigates the strong criticisms directed at the Frankfurt School and its legacy following more than a half century of prevailing influence in European and American academia, particularly in the social sciences where notions of cultural pluralism dominate the discourse. Conservative commentators have claimed that the Frankfurt School’s thrust has been entirely ideological, and it has eschewed empiricism to assault Western society through the production of countless identities—countless others—which are in explicit opposition to the dominant culture. Women’s liberation, the gay movement, minority interest groups and radical-progressiveness of all shades: conservatives view these as attacks on tradition and yet they are firmly ensconced in the academy and largely considered mainstream. But the overarching ideology of the ‘Other’ is defined solely by negation of the mainstream, say its critics. So, as the argument goes, the Frankfurt School’s formulation of alterity prevents authentic identity building because of its adversarial stance. The self is defined chiefly by what it is against, leaving scarce room for genuine self-affirmation and authenticity (Atzmon).

The opening salvo in this critique appeared in 1992 with the publication of Michael Minnicino’s “The Frankfurt School and Political Correctness” in the far-right American journal Fidelio. He writes that the “irrational adolescent outbursts of the 1960s have become institutionalized in a ‘permanent revolution’ [and] our campuses now represent the largest concentration of Marxist dogma in the world (3).” He traces this development to the 1920s, when the Institute for Social Research was established as a Marxist think tank associated with the University of Frankfurt and which became known as the Frankfurt School. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, global communism believed that the proletarian revolution would sweep into Europe and ultimately to North America. But it didn’t, so Frankfurt School theoreticians set out to implement Antonio Gramsci’s inspired judgment that social revolution occurs through the permeation and gradual command of the means of cultural production and policy-making, through cultural hegemony. Author Minnicini identifies the initial guiding light of the Frankfurt School, a Jewish Hungarian aristocrat-turned-communist named Georg Lukacs, a prolific cultural and literary critic who allegedly asked when joining the Communist Party during the 1st World War, “Who will save us from Western Civilization?”[1] It appears the Frankfurt School had a bone to pick with the West from the outset.