The Use of Force Continuum

Kate Flora here, writing today about the use of force continuum, which will be explained, a bit, in the Wikipedia excerpts below. Before I became a crime writer, I thought that what writers did was to sit at their desks, exercise their imaginations, and make things up. But whether I’m writing cops as my main characters–as in the case of my Joe Burgess series, or a civilian, or amateur detective, as I do in my Thea Kozak series, there are many instances in which I need to know how the police function, and knowing when an officer can fire a gun is part of that.

Kate Flora here, writing today about the use of force continuum, which will be explained, a bit, in the Wikipedia excerpts below. Before I became a crime writer, I thought that what writers did was to sit at their desks, exercise their imaginations, and make things up. But whether I’m writing cops as my main characters–as in the case of my Joe Burgess series, or a civilian, or amateur detective, as I do in my Thea Kozak series, there are many instances in which I need to know how the police function, and knowing when an officer can fire a gun is part of that.

At some point, several years ago, I met a police officer at the gym, and started peppering him with  questions. His response was to encourage me to attend a citizen’s police academy. Since my town didn’t offer one, he arranged for me to attend the one in the city where he worked. One night, part of the lecture on patrol procedure was on the use of force continuum…that system cops use to assess what level of force is appropriate, and necessary, in any given situation. I don’t remember what they told us about some of the less threatening situations, but I clearly remember the scenario where someone is coming at you with a knife, and they asked: At what point do you draw your weapon? At twenty feet, they told us, the knife-wielding assailant can get to you before you can get your gun out of your holster.

questions. His response was to encourage me to attend a citizen’s police academy. Since my town didn’t offer one, he arranged for me to attend the one in the city where he worked. One night, part of the lecture on patrol procedure was on the use of force continuum…that system cops use to assess what level of force is appropriate, and necessary, in any given situation. I don’t remember what they told us about some of the less threatening situations, but I clearly remember the scenario where someone is coming at you with a knife, and they asked: At what point do you draw your weapon? At twenty feet, they told us, the knife-wielding assailant can get to you before you can get your gun out of your holster.

Something else they told us, which has stayed in my mind ever since, is that that officer, in a dangerous situation, wants to go home alive at the end of the shift.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately, because of the events in Ferguson. Because they’re talking  about convening a grand jury way before they can possible have gathered the essential facts. Because there is so much angry talk about shooting an unarmed boy dead in the street when a detailed assessment of the situation is very complicated. I’ve been thinking about some of the videos police officers have shown me, and about how incredibly fast these things happen.

about convening a grand jury way before they can possible have gathered the essential facts. Because there is so much angry talk about shooting an unarmed boy dead in the street when a detailed assessment of the situation is very complicated. I’ve been thinking about some of the videos police officers have shown me, and about how incredibly fast these things happen.

I’ve also been thinking about my husband’s question–a question that seems to have been fueled by watching too many westerns where the sharpshooter zaps the gun out of the bad guy’s hand. And about what we’ve been told when crime writers go shooting with the cops–always aim for center mass. If you’re at the point where you’re going to shoot, you want them to go down and stay down. Try for an arm or a leg and the person might not go down. Or stay down. Never mind how truly difficult it is to aim and fire under stress or to hit a moving target. So no, dear, if you’re at the point where you’re going to shoot, you’re shooting to stop that person.

So here’s a brief discussion of the use of force continuum, plus a bit from the Supremes on what the after the fact test is.

From Wikipedia:

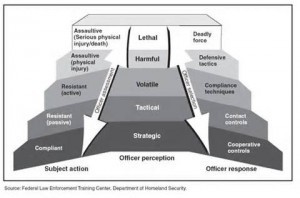

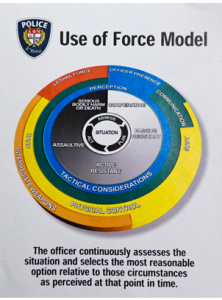

A use of force continuum is a standard that provides law enforcement officials & security officers (such as police officers, probation officers, or corrections officers) with guidelines as to how much force may be used against a resisting subject in a given situation. In certain ways it is similar to the military rules of engagement. The purpose of these models is to clarify, both for officers and citizens, the complex subject of use of force by law officers. They are often central parts of law enforcement agencies’ use of force policies. Although various criminal justice agencies have developed different models of the continuum, there is no universal standard model.

The first examples of use of force continuum were developed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Early models were depicted in various formats, including graphs, semicircular “gauges“, and linear progressions. Most often the models are presented in “stair step” fashion, with each level of force matched by a corresponding level of subject resistance, although it is generally noted that an officer need not progress through each level before reaching the final level of force. These progressions rest on the premise that officers should escalate and de-escalate their level of force in response to the subject’s actions.

Although the use of force continuum is used primarily as a training tool for law officers, it is also valuable with civilians, such as in criminal trials or hearings by police review boards. In particular, a graphical representation of a use of force continuum is useful to a jury when deciding whether an officer’s use of force was reasonable.

The United States Supreme Court, in the case of Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, (1989), held that when engaged in situations where the use of force is necessary to effect an arrest, or to protect an officer’s life or that of another, a law enforcement officer must act as other reasonable officers would have acted in a similar, tense, rapidly evolving situation.[6] Such situations, once known as use of force incidents, are now commonly referred to as response to resistance incidents, because a law enforcement officer must respond to resistance offered by another. In order to determine what actions officers find reasonable in similar situations, some experts utilize surveys with law enforcement officers, who are provided with certain scenarios to determine what actions they would take if placed in certain situations. Experts such as Samuel Faulkner, former instructor at the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy, not only surveys police officers, he has spoken to and surveyed, civilian review boards, high school and college government classes, Rotary Club and Kiwanis Clubs, Optimist Clubs, emergency managers, and even some chapters of the ACLU. Knowing what other officers and citizens deem reasonable helps to craft a solid response to resistance continuum.[7]

And one thing I’ve learned, by spending some hours today reading up on this, is that there is a movement now from the step-like format of the continuum to a use of force wheel, and much discussion about whether having to analyze the steps in an escalating situation might be seriously detrimental to officer safety.

And one thing I’ve learned, by spending some hours today reading up on this, is that there is a movement now from the step-like format of the continuum to a use of force wheel, and much discussion about whether having to analyze the steps in an escalating situation might be seriously detrimental to officer safety.

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 509 followers