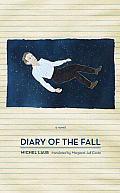

Michel Laub’s THE DIARY OF THE FALL :: Best of 2014, Probably

THE DIARY OF THE FALL by Michel Laub

THE DIARY OF THE FALL by Michel Laub

I hate handing out a title like “Best of 2014” so early in the year. I hate handing it out, in general, because now it seems like any of the other books I’ve written about from January to this point are explicitly not the best, but there is no getting around it: Diary of the Fall struck me like no other book has this year. In a just world, it will be studied in schools alongside Elie Wiesel’s Night and Camus. It will be brought up in philosophical debates, when questioning the meaning of human suffering and humanity’s existence. This is not hyperbole.

It’s easy to underestimate. The book is literally the same length as my hand, from wrist to fingertips, and about as wide as my fingers naturally sit. It is easy to mistake for a tabletop book. Please do not make this mistake. The way the story is divided with chapters only paragraphs in length, numbered in the middle of pages, may make you think this is flash, pieces unrelated to each other. Do not make this mistake, either – every piece of the entire story connects together, forming a whole.

The story starts with the story of João’s fall. A Catholic boy in a class filled with 13 to 14 year old Jewish boys, João is teased, told to eat sand, criticized and mocked as the other. His father works as hard as he can as a bus conductor, overtime selling cotton candy in the park to pay for his son’s tuitions, adamant that his son get the best education possible. The young boys do not connect the blue-collar father to the hatred of the son; they are simply, childishly filled with contempt for the boy.

It’s a popular tradition of the boys that, on a young man’s birthday, friends gather around, hoist the boy in the air and toss one two three, and catch him safely. But on João’s birthday, they let him drop.

The fall sets off a chain of events that forever change not just the life of João, but of one of the Jewish boys who was there, who let him fall, who years later, still struggles to make peace with the injustices he committed as a child.

Soon enough, the novel is no longer about this isolated case of prejudice, this case of spite and hate and pain. It evolves into a tale of the most horrifying pains in the world, the unhealing wounds, the cuts that refuse to scab over so easily.

The narrator of the story, an unnamed journalist now in his 40s, decided to switch schools at the end of the year, to join João at his new school, even though it means he will now be the only one who is Jewish. A catalyst is started, with the narrator learning more, becoming more aware of his heritage and what it means to be Jewish in modern times.

Digging into his past, the narrator learns about the obsessive writings of his grandfather, a man who unlike so many, survived the horrors of Auschwitz, who later in life, poured hours alone in his room writing in journals false memories about the way life should be rather than the truth. His family, all of whom died in concentration camps, the horrors of war, are never mentioned. Later, his own father succumbs to Alzheimer’s, his mind failing slowly. His father uses the time he has to record the copious details of his life, the truth he is desperate to pass onto his son, one section sent at a time.

Sorting through his forefather’s works, the narrator comes to terms with his own weaknesses, his own desires to hide the pain, his own need to record the truth, hurt as it may.

I couldn’t believe how knocked away and emotional this all was. It’s like 200 pages, and I feel like a meet an entire family, learned their secrets, cried for each as he suffered from war, from Alzheimer’s, from, as we learn later about the narrator, battles with alcoholism.

I can’t help you if you think World War II stories are overused at this point. It is a subject I will never be able to ‘get over,’ despite never having lost more than maybe a great-uncle to that war. Yet, even the narrator recognizes the exhaustion most people have to these narratives, to the accounts of atrocities suffered at camps, to the horrors humans were put through, worse than any horror film could imagine:

“Would it make any difference if the things I’m describing are still true more than half a century after Auschwitz, when no one can bear to hear about it anymore, when even to me it seems old-fashioned to write about it, or are those things only of importance to me because of the implications they had for the lives of all those around me?”

I understand the holocaust does not represent my pain. I lost no one to the camps. It’s larger, though. It’s a pain that shows just how god-awful humans can be to each other, how long the body can suffer before collapsing into dust, how cruel the world can be and how soon we can stop caring to you talk of your pain.

You might never connect the story of one little boy being dropped by his classmates to the horrors of Auschwitz. These are incomparable in terms of human suffering. Yet, in Michel Laub’s prose, all pain connects, feeds, and tries to understand each other.

This is one of the best books you can read this year, for many years, maybe.