Pacing, Plotting, and Causality

Plotting is in the story itself. Pacing is how the writer unravels the story.

Plotting is in the story itself. Pacing is how the writer unravels the story.

First, what makes up a good plot? Interesting characters doing either interesting things, or placed in challenging situations that test their beliefs and resolve is what keeps readers turning pages. But is that all there is to a plot?

No one wants to read about two university graduates at the top of their class, who get good jobs, meet and then marry. They have two perfect children who also get good grades and are always well behaved. The couple stays faithful and in love until they die at age 100 within minutes of each other.

Although we might wonder how they do it, what that plot lacks is a lot of C. C stands for Conflicts and Challenges in their lives. That mythical couple would be as boring as a detective with no crime to solve, rolling thumbs at his desk, and waiting for a call that never arrives.

Plots can be event, character and/or theme driven as long as there is something that makes readers want to keep reading: suspense. Once the plot is in place then pacing comes into play. (Apologies for the alliteration.)

There is no single way to structure your pacing.

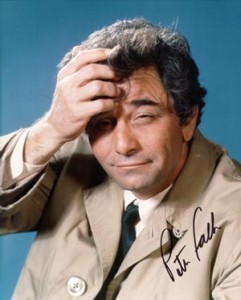

The end can even be revealed in the beginning, and the rest of the story can show how the end was reached. Think of all the COLUMBO series. We know from the first few scenes who the murderer is, but then we’re glued to the TV to watch Peter Falk and his raincoat and his famous “One more question” to bring down the guilty party.

Some novels start with a prologue that we know at one point will make sense.

For example the warnings the human race receives — and ignores — before the Apocalypse strikes in Daimones .

.

Other times we don’t know how the story ends (unless you are one of those who reads the last page first: too much of Columbo watching). The writer drops hints along the way, and hints are necessary because a reader will be angry if the ending lacks believability. Better that s/he thinks, how clever the writer was to sneak in the clues that went missed.

A good example of sneaky clues is the film THE SIXTH SENSE (Nebula Award for Best Script.) Although the ending seemed like a surprise, when rethinking different scenes all the clues are there.

The writer must decide what to give away and when.

Pacing also involves tension. We need to vary the tension and its pace to not exhaust or bore our readers. You need to vary the pace of your sentence, too, but that’s another issue.

One way to go is with sub plots, making the reader wait to see what happened to character A as we follow character B. Sound to you like cliffhangers? Yes, in a sense, but at least you don’t have to wait for the next book in a series to know what happens. While cliffhangers within a novel keep the tension and create suspense, if I were to put a cliffhanger at the last page of my novels I’d fell like I’m cheating my readers. But opinions differ on this subject.

In short stories there is usual only one plot, but in a novel we can have several different sub plots intersecting. A master at weaving subplots together is John Irving.

there is usual only one plot, but in a novel we can have several different sub plots intersecting. A master at weaving subplots together is John Irving.

With different story lines in a novel we can pick up one while putting another aside. Think in terms of three interwoven sub plots, A B C. The lines are different lengths to show the amount of space devoted to each subplot. It does not need to be equal. However, at the end they must all be resolved. No cliffhangers.

A____B_______A_C______________AB_________C_________CB_______ABC

Not all subplots need to be of the same strength giving us A b C

A_________b__C___________A________bC_____AbC

“Plot is the structure of events within a story and the causal relationship between them. There is no plot without causality.” – S. Andrew Swann

“According to Aristotle’s Poetics, a plot in literature is “the arrangement of incidents” that (ideally) each follow plausibly from the other. Aristotle notes that a string of unconnected speeches, no matter how well-executed, will not have as much emotional impact as a series of tightly connected speeches delivered by imperfect speakers.” The lesson here? A great story and its plot, even with some technical imperfections, will beat a dull but perfectly written novel

“The concept of plot and the associated concept of construction of plot, emplotment, has of course developed considerably since Aristotle made these insightful observations. The episodic narrative tradition which Aristotle indicates has systematically been subverted over the intervening years, to the extent that the concept of beginning, middle, and end are merely regarded as a conventional device when no other is at hand.” Remember that at your next creative writing class!

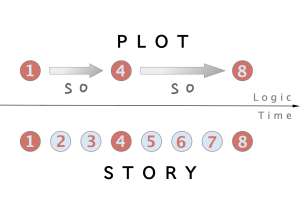

Lot of a story will extend beyond the bounds of the story itself, but suffice to remember that a plot is a summary of a story, and composed of causal events, which means a series of sentences linked by “and so.” The Causality of the events is what makes a plot. Whereas a story orders events from A to Z in time, the plot makes the logical connection with one event to another in the story (not necessarily the next one) but takes place because of the preceding one.

For Aristotle (as it should for everyone), the plot is the most important element in a story, and the events of the plot must causally relate to one another as being either necessary or probable. Aristotle goes on to consider whether the tragic character suffers (pathos), and whether or not the tragic character commits the error with knowledge of what he is doing, his/her challenges.

Thus, plot your story, and add logic to the events. It’s nothing really new.

Allow me to conclude with the citation from Sallustius that appears in Daimones .

.

“These things never happened, but they are always.”

“Deorum naturae neque factae sunt; quae enim semper sunt, numquam fiunt: semper vero sunt.” – Sallustiu

The post Pacing, Plotting, and Causality appeared first on § Author Massimo Marino.