The Pliocene Adventure -- Herbivores (Browsers) Part 1

The herbivores of the mid-Pliocene of Denver, Colorado, represent the single largest group of animals in the area, both in terms of diversity and in sheer numbers. This is to be expected, considering that they serve as prey for predators. The savanna located in the plain between the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains and the Aurora ridge is particularly rich in plant life, which not only supports the diversity and numbers, but also the various megafaunal creatures. It is well-watered, both by rivers and springs flowing out of the mountains and the ridge, but also by seasonal winter rains, plus the occasional summer thunderstorm. These support numerous trees. Nonetheless, total precipitation is low, and that combined with poor soil, grazing, and lightning wildfires prevents the trees from taking over completely.

The herbivores of the mid-Pliocene of Denver, Colorado, represent the single largest group of animals in the area, both in terms of diversity and in sheer numbers. This is to be expected, considering that they serve as prey for predators. The savanna located in the plain between the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains and the Aurora ridge is particularly rich in plant life, which not only supports the diversity and numbers, but also the various megafaunal creatures. It is well-watered, both by rivers and springs flowing out of the mountains and the ridge, but also by seasonal winter rains, plus the occasional summer thunderstorm. These support numerous trees. Nonetheless, total precipitation is low, and that combined with poor soil, grazing, and lightning wildfires prevents the trees from taking over completely.The trees present are predominantly oaks, but also hickories, basswoods, and maples, with cottonwoods, ashes, and aspens. On average, the trees do not grow dense enough to create a closed canopy. As such, the open-canopy environment supports many tallgrass prairie species, as well as some forest species. These include forbs and shrubs as well as tall and short grasses. However, tree density is not uniform. There are places, especially river or pond riparian zones, where the trees do grow dense enough to close their canopies, and other places, mostly above the rivers, where the trees grow more sparsely, with a few places where there are none at all. The mix of environments allows the herbivores to segregate themselves: some live on the prairie-like expanses, some in the open-canopy savannas, and the rest in the forest-like closed-canopy woodlots. Some can move freely from one environment to another, while others never leave the one that serves them the best. Even so, those that move around still prefer one environment over the rest. Meanwhile, the ridge most likely was covered by scrub and brush, since there would be too little soil to support trees and grasses, while the foothills of the mountains were covered with conifers.

The animals were most likely residents rather than migrators, because both the mountains and the ridge would have made long-range east-west passage difficult. However, the plain most likely stretched from Boulder in the north, or even as far as Loveland, to Colorado Springs in the south, with its widest point at Denver, giving it a very large area. It is conceivable that a north-south migration might have taken place between summer and winter, and gaps did exist in the extreme north and south that would have allowed access to the prairie beyond the ridge.

Herbivores use one of two different methods to feed: grazing and browsing. Grazing is the consumption of the whole plant, or nearly so, while browsing is the consumption of parts of it: leaves, shoots, twigs, seeds, fruit, bark, or roots. Many grazers eat grass, but this is not required, though some herbivores are very specialized, eating just one species of plant while ignoring all others or eating just one part of a plant, while the rest are more general, with some that are virtually omnivores, even eating insects and small animals. No herbivore is completely one type of feeder or the other. Some are both, while even those that are predominantly one type will switch to the other out of necessity. Furthermore, a genus may have some species that are grazers and some that are browsers. Switching can be done for a number of reasons. For example, a wild goat might browse during the summer or the wet season, then switch to grazing in the winter or dry season. Migratory animals can switch because the same plants are not available in the different places they travel to. Other creatures switch if the opportunity presents itself, such as a rabbit switching from grazing grass to browsing on lettuce in a garden. Some switch back and forth throughout their lives, as the local weather shifts through a multi-year or decade cycle of monsoons and drought. Then there are creatures who graze and browse virtually simultaneously as they forage for food.

Because of the number of animals involved, I have divided the list of herbivores between four posts. Today's and next week's will discuss browsers, while after that I will present the list of grazers.

Once again, the genus name for each creature is given in parentheses.

Beaver (Castor) -- This is the contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. Beavers were responsible for keeping North America well-watered and stocked with wetlands, which in turn encouraged the evolution of many wetland species of plants and animals.

A mated pair created a series of dams in a streambed fed by a spring and rainwater runoff from the ridge where Team Girl and Differel live. The site is below their cave and slightly south, giving them a nearby abundant source of freshwater. The spring water is fairly clean, so the primary pond, which is the largest and nearest, is also fairly clean and clear, except right after a rainstorm. The series of smaller ponds further downstream, however, pick up a fair amount of sediment and are cloudier. TG and Differel often swim in the primary pond, and fish and gather edible plants, crayfish, and clams from it to supplement their military rations. However, it is also a waterhole for local herbivores, including some megafauna, and their predators.

Beavers, Giant -- These Genera are extinct. They are the ancestors of the Pleistocene megafaunal giant beaver, and are themselves megafaunal animals. This lineage diverged from the modern beaver millions of years before the mid-Pliocene and are marginally more primitive than modern beavers. The Pleistocene Genus grew to be as big as a modern black bear.

(Dipoides) -- This is the second-to-last Genus before the emergence of the Pleistocene giant. It was twice as big as a modern beaver.

(Procastoroides) -- This is the last Genus before the emergence of the Pleistocene giant. It was about two-thirds the size of the latter.

These guys need more room and access to larger, more numerous trees than the modern beaver. TG and Differel find two families of Dipoides, one on Clear Creek next to the Front Range foothills, and one on Cherry Creek to the south, as well as a family of Procastoroides on the South Platte further north. Their larger ponds, almost like small lakes, serve as the major water sources for the savanna, along with the three rivers. The majority of the megafauna use these other sources rather than the beaver pond under the cave.

Camel, Goat (Capricamelus) -- This Genus is extinct. It derives its name from its goat-like body structure, particularly its legs.

Capricamelus evolved to negotiate rougher, often rocky terrain, like a goat, but otherwise resembles a llama. Unlike other camels, it browses to take maximum advantage of whatever food source is available. TG and Differel have seen goat camel herds on the heights of the ridge above their cave.

Chipmunk (Neotamias) -- This is one contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It lives in the closed-canopy forest woodlots and riparian zones. It is instrumental in the dispersal of tree seeds and fungi spores, and will cross semi-open or short stretches of open country to reach new woodlots, thereby spreading tree species over a wide area and helping to expand the woodlots. They tend to be omnivorous, also eating worms, insect, small vertebrates, and bird eggs.

These guys are like tiny bears. Though wary, they can get into almost anything where they detect food, and they are almost impossible to deter. Though they are not a nuisance in TG/Differel's home cave, they tend to get into their food caches when they sleep overnight in a woodlot.

Deer (Odocoileus) -- This is one contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. Though not true megafauna, they are somewhat larger than modern species, possibly in response to the presence of large, powerful predators. They are the epitome of the newly emerging modern animals that will survive the Pleistocene extinction and replace virtually all of the savanna grazing herd species.

These guys spend most of their time in the closed-canopy and denser open-canopy woodlots, away from the larger predators and to avoid competition with the numerous savanna grazing herd species. Their willingness to eat a wide variety of plants allows them to utilize a wide variety of habitats, and they will venture out onto the savannah at night or when the herds have largely moved on in their seasonal north-south migration. When TG and Differel need fresh meat, they prefer to hunt these guys, because they are closer, less dangerous, can be ambushed from a blind, and there are fewer dangerous predators around them.

Gopher, Horned (Ceratogaulus) -- This Genus is extinct. These rodents were larger than modern gophers, almost as large as modern marmots, qualifying them as megafaunal animals, though in absolute terms they were only a foot long. They had two large horns on the tops of their snouts that were most likely used to fight off predators. They had poor eyesight and were burrowers.

These guys were already dying out in Colorado by the mid-Pliocene. TG and Differel find a small isolated colony of a dozen individuals, but throughout the year they were in the past they never saw any offspring, leading them to believe the colony was dying out.

Gophers, Pocket -- This creature comes the closest to being a rodent version of the mole. They spend the vast majority of their lives underground, emerging only to find food or mates, so they have poor eyesight and are adapted to conditions of low oxygen and high carbon dioxide. They feed primarily on roots and tubers, but will also take grass. They prefer loose, dry, sandy soils. They can be aggressive towards predators. They tend to be omnivorous, eating also worms and grubs.

(Cratogeomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and its Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species.

(Geomys) -- This is a contemporary Genus, and its Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species.

(Nerterogeomys) -- This Genus is extinct.

As a minor plot point, TG/Differel manage to find out what local plants are edible using an analysis device Mabuse sent back, and much trial and error. They decide to put in a vegetable garden, but while they manage to keep the larger herbivores at bay and accept some losses from the smaller ones, a single gopher devastates their garden, and despite their best efforts they can't catch it. After they give up, however, the garden spreads on its own, and it isn't long before they can harvest some veggies while leaving the rest for the gopher.

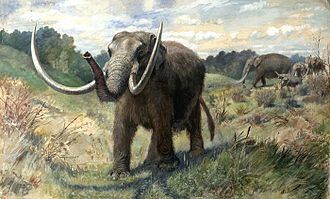

Gomphotheres (Cuvieronius) -- This Genus is extinct. The Gomphotheres were a group of elephant-like animals that closely resembled modern elephants in body, but had a diverse variety of jaw and teeth forms, and flatter foreheads. It's possible they were not as intelligent as modern elephants. Some Gomphotheres had four tusks; some had elongated upper or lower jaws or both with short tusks, while others had short jaws and long tusks. Some had a mix of both. Later Genera could be mistaken for mastodons. Their facial structure suggests they all had long trunks.

Cuvieronius strongly resembles the mastodon, but with spiral tusks. It stood 9 feet tall at the shoulder. Its teeth and isotopic analysis of its bones suggests that it ate a mix of plants, from both the ground and higher up.

TG & Differel discover a single herd that travels along the Front Range, feeding on the margins of the pine forests that cover the foothills.

Kangaroo Rats -- These small rodents are bipedal, with large hind legs that allow them to jump like kangaroos, hence their popular name. They also have exceptionally long tails for their size. They can make their own water metabolically, but they take advantage of whatever sources lie within their territories. While primarily seed-eaters, they will eat insects, too.

(Dipodomys) -- This is one contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species.

(Prodipodomys) -- This Genus is extinct. "Early kangaroo rat"

As a minor plot point, shortly after TG & Differel first arrive and set up camp in the cave, a kangaroo rat visits them. Kitty chases it, but can't catch it. It becomes a regular visitor, but Kitty can never catch it and finally gives up. That's when Sunny starts calling it Muad'Dib. It visits on average five times a week, and they soon learn that when it is out and about they can go outside because it is safe, but as soon as it disappeares they know a predator is about and they have to get back into the cave. It remains their companion the entire time of their stay, and it watches them go back into the future.

Lemmings -- These are small rodents that are larger than mice but smaller than rats. They have very short tails, and so resemble hamsters. They prefer moist environments, but can live anywhere from closed-canopy woodlots to open grasslands, as long as their is plenty of moisture. They are active in the winter, and will tunnel and forage under the snow. They can be aggressive towards predators. When local population pressure becomes too high, they emigrate, even crossing bodies of water to find new territories. They are subject to sudden population crashes. They can be omnivorous, eating grubs and other larvae.

(Mictomys) -- This Genus is extinct.

(Plioctomys) -- This Genus is extinct.

(Pliolemmus) -- This Genus is extinct. "Pliocene lemming"

(Synaptomys) -- This is one contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. It is called the bog lemming because it is often found in bogs, but it can live anywhere wet.

TG/Differel note that the only lemmings they can find are in the margins of the ponds formed by the beavers, because they create marshy and boggy habitats, whereas the riparian zones along the rivers are too dry. A good sized colony has established itself around the lower ponds below the cave, which are starting to silt up and forming bogs.

Marmot (Marmota) -- This is the contemporary Genus, and the Pliocene species is virtually identical to the modern species. These are large ground squirrels that live in rocky habitats because they prefer to burrow under rocks for extra protection. They live in colonies that consist of a limited number of males and their harems of females. When they see danger they whistle to alert their neighbors. They spend most of their time in their burrows when not foraging for food. They will hibernate if the weather gets too cool. They tend to live on slopes. They can be aggressive towards predators. They are omnivorous, also eating insects and bird eggs.

TG & Differel find several colonies strung out along the line of the ridge where their cave is located, but they also notice that there are a few colonies on the plain at the base of the ridge. They take to calling them rock marmots and groundhogs, respectively. They sometimes hunt them when they want extra food.

Marmot, Giant (Paenemarmota) -- This Genus is extinct. It is the megafaunal version of its family, being twice the size of a modern marmot (3-4 ft long). Its lifestyle was more like the modern goundhog, in that it lived in lowland open country. It formed colonies like its smaller cousins and lived in burrows.

TG & Differel discover that Paenemarmota lives in open-canopy savanna or grasslands on the edges of closed-canopy woodlots. They warn each other of danger, but tend to be aggressive towards predators. They are accomplished swimmers and can even climb stout trees like bears. They are more herbivorous than their smaller cousins, but they will take small animals and bird eggs if the opportunity presents itself.

Mastodon (Mammut) -- This Genus is extinct. This is one of the two most famous elephant-like creatures in North America, the other being the mammoth. Compared to modern elephants, mastodons were shorter (7-8 ft at the shoulder), longer, and bulkier, with long low skulls with flat foreheads and much longer tusks that curved upwards. Their teeth were adapted for eating tree leaves and twigs, not grass (though they probably ate grass and other ground plants during certain times of the year), so they preferred to live among trees rather than open grassland. They were social like modern elephants, with females and young forming herds and the males mostly solitary.

The Denver plain (as TG have named it) boasts a few small herds and 2 or 3 solitary males. The herds maintain travel territories that are separated by "no-mastodon's-lands" that keep them well separated, while the males range more widely and freely. They prefer the open-canopy savannas and feed along the edges of the closed-canopy woodlots, but occasionally venture out onto the open grassland to graze. The males spend most of their time in the grassland and go into the open-canopy savanna mostly to feed, but sometimes to mate.

TG-Differel's observations verify that mastodons are social, and they are surprised by the degree of emotional attachment and affection they display. One herd, the smallest with four females and three youngsters, makes periodic visits to the beaver ponds to drink and feed on water plants. In addition to their own aggressive defense of their young, the mastodons are followed by apex predators, so TG and Differel stay away from the ponds whenever the resident herd comes to visit.

Continued in Part 2.

Published on September 01, 2014 10:21

•

Tags:

animals, browsers, herbivores, pliocene

No comments have been added yet.

Songs of the Seanchaí

Musings on my stories, the background of my stories, writing, and the world in general.

- Kevin L. O'Brien's profile

- 23 followers