Raised on Boring Workaholic Athletes Who Happen to be Super White

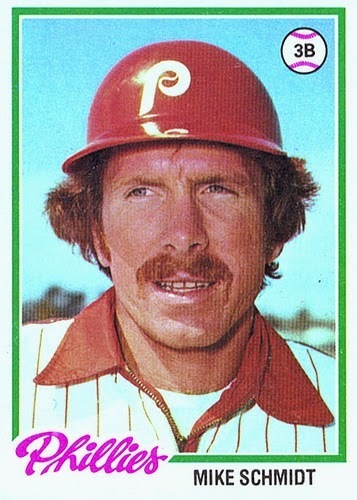

When the correspondent from ABC’s Good Morning America asked 10-year-old me what I wanted to be when I grew up I didn’t need too long to think. “Third basemen for the Philadelphia Phillies,” I responded. I caught my reflection in the lens of the hulking television camera before me; I had burly side-burns and spit chaw, while clad in mid-80’s Phillies home pinstripes. All I needed was about twelve more years developing superior glove-work and defensive range while harnessing the hand-eye coordination and nearly superhuman raw power to lead the National League in home runs eight times and earn an NL MVP nod three times. Okay. Okay. I wanted to me Mike Schmidt. I wanted to me Mike Schmidt because I grew up emulating Mike Schmidt. I grew up emulating Mike Schmidt because he was my father’s favorite baseball player. He was my father’s favorite baseball player because he was the best player on his favorite team. He also embodied the default benchmarks that typified my father’s favorite athletes: he was boring and a workaholic who “played the game right.”

Why was Good Morning America interviewing me? I was chosen as South Williamsport Area Grade School’s “Whiz Kid of the Year” and was invited to the White House to meet Ronald Reagan with other northern Pennsylvania “whiz kids”. Psyche! My Little League team was coached by a gentleman named Fred Heaps, who had been coaching Newberry Little League teams for nearly 40 years at that point. His most notable achievement was leading a local team to the Little League World Series in 1969. More importantly, he was known for doing kindhearted things like buying baseball gloves for kids who couldn’t afford them, or reminding his teams that he loved them, win or lose. What I remember most about him was how he preached “fundamentals, fundamentals, fundamentals,” and giving me a quarter for answering “Tony Gwynn” when he asked who was the purest hitter in the major leagues. ABC put together a piece on Fred Heaps during the MLB All-Star break in 1988. Coach Heaps passed away two years later, during my final year as a little leaguer.

Goddamn, I miss little league.

I read Mike Schmidt’s autobiography Clearing the Bases: Juiced Players, Monster Salaries, Sham Records, and a Hall of Famer's Search for the Soul of Baseball (ahem) a few years ago. Schmidt lays bare the lack of fun that accompanied his 18 years with the Phillies, from ’72-’89. Essentially, Schmidt put such incredible pressure on himself to be an elite player that he had tremendous difficulty squeezing enjoyment from playing the game. To the detriment of all life’s simple pleasures, his priority was training his body, and developing the mindset, to consistently be at peak potential. The theater of baseball was for the birds. Schmidt didn’t insult the pitcher, or the game, by brazenly flipping the bat after crushing a ball that would clearly sail high over the left-center fence, as Yasiel Puig does today. He didn’t take an hour and a half to leisurely trot around the bases after a home run, as David Ortiz has trademarked. He wasn’t known for childish off-field antics prompting observers to say, “oh well, that’s just Schmidt being Schmidt,” such as whenever Manny Ramirez pulled a boner and the world muttered a collective, and exhausted, “ugh, that’s just Manny being Manny.” (For purposes of supporting the premise, I’m excluding rumors that Mike Schmidt used cocaine during his playing days, or the time he was a guest Phillies color commentator and sprang an off-handed joke about beating his wife. Schmidt’s career has never been typified by drug rumors or “Manny Moments” so I think it’s okay to omit such from the conversation.)

Mike Schmidt the baseball player was exciting. He hit majestic home runs. He was a wizard with the glove as a third basemen. He was one of those generational players who had the capacity to pull off something dramatic or extraordinary at any moment during a game. But Mike Schmidt the personality was boring. And my father loved him. Schmidt was his kind of player. If Mike Schmidt the personality was the equivalent of a career, that career would probably be -- banker. Dad was a banker for the vast majority of his working life. And he was a damn good banker, too. He was promoted to vice president of Sun Bank during that glorious ’01 fiscal season. In fact, one could argue that my father was the Mike Schmidt, or at least a Mike Schmidt, of the north central Pennsylvania banking industry; he never brashly flipped his suitcase or trotted a victory lap around the stanchions in the lobby for, ah, any reason that would cause a banker to celebrate. He certainly was no Reggie Jackson. Reggie “Mr. October” Jackson was that flashy post-season world-beater who said things like “I didn’t come to New York (to become a Yankee) to be a star. I brought the star with me,” and “The only reason I don’t like playing in the World Series is I can’t watch myself play.” Sure, Jackson was a terrific player, but what sickening bravado! He should’ve just shut up and played the game, I tell you. He was a “turkey,” as Dad was/is prone to calling strutting athletes like Jackson. On the other hand, one of Schmidt’s notable quotes was “Anytime you think you have the game conquered, the game will turn around and punch you right in the nose.” Now that’s modesty, boy. That’s the mindset of a guy who plays the game right. Now where’s my briefcase and penny loafers, I gotta’ get to the office and a barrel-load of paperwork.

Mike Schmidt retired in 1989 (and was voted a first ballot Hall of Famer five years later). About this time people began to notice that I was somewhat rangy for my age. Of course, no expression of my height was without the obligatory “You should play basketball.” So I did, honing what skills I had at the local playground. I also became a fan of the NBA. I hitched my fandom on to my father’s favorite basketball player, Larry Bird. Larry Bird was about as boring a basketball player as could be. I mean, he was exciting, in that he was dominant on the court. But he was boring in the sense that he didn’t finish fast breaks with a tomahawk jam, or hop on the scorers’ table and strike a triumphant pose, or spit catchphrases after the game. Bird? He hit mid-range jump shots, laid the ball off the glass, and treated the media like invading bacteria. In fact, the single existing clip of him dunking the ball has appeared ad nauseum on Larry Bird highlight reels. As a matter of fact, his most recognizable highlight was a friggin’ inbounds steal; “And… now there's a steal by Bird, underneath to DJ and lays it down... What a play by Bird. Oh my God. This place is crazy.”

Larry Bird was born in the tiny farm community of French Lick, Indiana. His youth was dedicated to back-breaking manual labor, and, as far as Bird knew, would always be. Even when he accepted a scholarship to Indiana University -- one of the most decorated collegiate basketball programs in the county -- he bailed out when life at a big-time university proved too overwhelming. He later enrolled in the less prestigious Indiana State University basketball program, where he single-handedly took the Sycamores to the NCAA national championship game in '79. Even when Bird's father committed suicide, he was resolute -- kick ass on the court and remain discreet off of it. THIS GUY, my friends, was not only born to win NBA championships, but also to be one of my father's favorite athletes.

Larry Bird's greatest foil on the court was -- no drumroll needed -- Earvin "Magic" Johnson. Bird and Johnson met in the aforementioned NCAA championship game, and again in the NBA championships 3 times. But the comparison delves so much deeper. Their nicknames alone are clue enough that a discerning mind would recognize which player my father would idolize.

"Magic": Flashy. Gaudy. "Look at me, everyone."

"The Hick From French Lick": See word "Hick."

However, Magic was the perfect antithesis to Bird. Magic's team was the "Showtime" LA Lakers. Magic's cheesing mug was on billboards and television commercials. Magic bedded nearly as many women as he had amassed career assists. One the other hand, Bird's Boston Celtics mirrored gangly white working class schlubs in both appearance and attitude (yes, Robert Parish did, too). Off the court, Bird's face only appeared in his defender's dreams. And I'm pretty sure Bird is still a virgin.

Okay, here's the example that perfectly epitomizes Dad's affection for Bird over Magic. While Magic was romancing one woman after another on velvet bedspreads, Bird was putting in his mother's driveway. As a result -- Magic got AIDS, and Bird got a chronic bad back. To be fair, Magic has earned my father's respect. Johnson was, and is, a true professional and a stand-up human being (despite now being part-owner of the blasted LA Dodgers). But whenever Dad is outside building a retaining wall or hauling dead trees, he is Larry "The Hick From French Lick" Bird, but in Dickies work pants and a flannel shirt.

The other sport my father enjoys is football. His favorite NFL player should be exceedingly easy to guess. (Dad doesn't pay attention to hockey. His head would explode trying to determine a favorite player because every NHL athlete is either Mike Schmidt or Larry Bird on ice skates, more-or-less. I think Alexander Ovechkin would be the only guy off the table.) That player is Peyton Manning, duh. dad has always been a diehard Baltimore/Indianapolis Colts fan, to boot. Peyton Manning is the stereotypical overacheiver. His workaholic credentials are legend. In fact, he's such an overachiever that he's rife for satire -- he shows up to training camp before Valentine's Day; he breastfeeds rookies (in public) until they're mature enough to put on pads on Week One; he's competed in the playoffs with a severed head.

The Colt's vaunted starting quarterback sat out the 2011 football season due a faulty neck. That year, replacement quarterback Curtis Painter "led" the Colt's to a 2-14 record, ensuring Indianapolis the number one pick in the 2012 NFL draft. The team had since decided to draft a young college quarterback to replace a departing Manning, The two choices were obvious: Standford QB Andrew Luck or Baylor QB Robert Griffin III. Both were tremendous talents who had celebrated college careers. Both were also dedicated and hardworking athletes who were, by all accounts, respectful human beings. Dad liked them both. Prior to Draft Day he stated in an email to me "I'd gladly take either Luck or Griffin." Either player seemed fully capable of eventually returning the Colts to the Super Bowl. To Dad, the variables of the quarterback were irrelevant. Leading the team to victory was paramount. However, all things being equal, I knew my father preferred Andrew Luck. Why? Luck was boring. He fit perfectly the comfortable Schmidt/Bird prototype.

During the 2012 NFL season, Luck spearheaded a Colt's offense to an 11-5 record. RG3 led the Washington Redskins to the same record. Both teams made the playoffs. That Thanksgiving, I was watching the football games at my parents' house with my father when a Subway commercial aired, starring Robert Griffin the Third. Dad grimaced and shook his head, and said "See now, that bothers me. This guy is only a rookie and he's doing television commercials." I reminded him that Peyton Manning has literally been in every other friggin' commercial for five years straight. I should've imagined his response; "That's right. He's already won the Big One." Touche'.

I never grew up to be the baseball player in the camera lens. Sure, I could've grown badass sideburns and stuffed chew under my bottom lip, but I was destine to not be Mike Schmidt. As much as I daydreamed -- even if I'd tried like hell since I was a little leaguer -- I could never have become Reggie Jackon, or Larry Bird, or Magic Johnson, or RG3. I never wanted to be Peyton Manning -- he who sacrificed a puppy to Satan in exchange for a first-round playoff bye, or appeared in enough Starbucks commercials to gain membership in the Screen Actor's Guild.

I'm not upset that I never achieved my childhood dreams. Nevertheless,I do possess the capacity to build a retaining wall or haul dead trees. Hell, I suppose I could even lay a driveway if I really, really want to. In the minds of some, completing such chores is the everyman's version of winning the Big One.

Published on August 12, 2014 13:52

No comments have been added yet.