Lessons my father taught me

If you’re lucky enough to be raised by a good father, as I was, you may be tempted to hold him up as the epitome of all fathers. But I’m not one of those daughters. I know my dad wouldn’t want to be elevated to an impossible standard of perfection. He isn’t perfect. Neither am I.

I’m the kind of daughter to really test a parent’s patience. I guess by most people’s standards, my antics weren’t that crazy: I never went wild with drugs, alcohol, or gangs (though I did get tattooed, and Dad was less than thrilled about that). I’m the daughter who defied family tradition by going to church when I was raised in synagogue. Took the risk of permanently hurting his feelings when I legally changed my name (it was his grandmother I was named for, after all).

In recent years, we fought over things: some legitimate, but mostly not. We said some hurtful things. I took the first chance I got to move 1,500 miles away, with no intentions of turning back.

I could have been a lot better. I could have done a lot worse. That applies to both of us.

It sounds strange, but cancer didn’t seem like a big deal at first. At age twelve, I knew plenty of people died from it – but they were all elderly. My dad was still young and healthy. We live in a first-world country with the best medical treatments available. He’d be fine.

I often ask myself which is the better scenario: to have a loved one taken from you in an instant; to be woken up by a frantic phone call in the middle of the night, alerting you that your relative was struck and killed by a drunk driver, or shot in a drive-by, when the real target was the guy standing behind him. Or, is it better to know ahead of time that your loved one is dying by degrees; to prepare accordingly, and say what you need to say before the moment is gone forever.

Both are tragedies. I can only speak some degree of wisdom about the latter.

For me, I needed those extra years. Who’s to say I wouldn’t still be in Colorado right now, living my own life, without concern for making amends. I’ll be honest: I am the kind of person who is sometimes content to leave things broken because the effort to try and fix them is too time-consuming and too humiliating. I’m someone who needs time to stew for a while before I can start being a grown-up and clean up my messes. But sometimes I just don’t.

My dad, thankfully, is the opposite. I have his hair, his nose – his whole face, really – but not as much of his personality as I’d like: the kind of traits that would make my life a lot easier, because they would improve the quality of my relationships with a lot of people.

My father wouldn’t let me run away. He called me, faithfully. Sent me funny cat memes on Facebook. Waited anxiously for me with my mom at the airport on holiday breaks. Unlike me, he is not a grudge-holder. He’s a man who knows that time is precious.

For years, I watched the cancer cripple my father. I watched, with increasing devastation and helplessness, as my previously active father, head coach of the high school track team, began to lose his mobility. It’s as ugly as you can imagine.

But the one comfort I have in this shit-storm is the knowledge that there’s nothing else I need to say that hasn’t already been said. At the end of the day, nothing matters more than “I love you,” and I say it as often as I can, while I can. Everyone should.

I don’t have a perfect dad (no one really does). But I have a dad who doesn’t believe in wasting anything, whether it’s leftover wine sauce from dinner, plastic bags to scoop up dog poo, or a limited amount of days. I have a father who knows how to make those days count. My uncle, his brother, asked if he’d want to just travel as much as possible, soak up as many new experiences as he could. That may appeal to some people, but that’s not what Dad wanted. He only wants to be with his family.

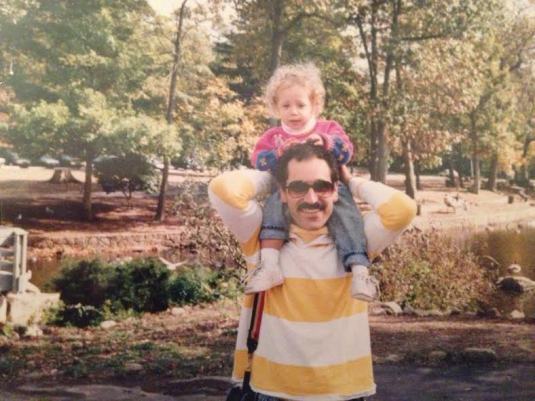

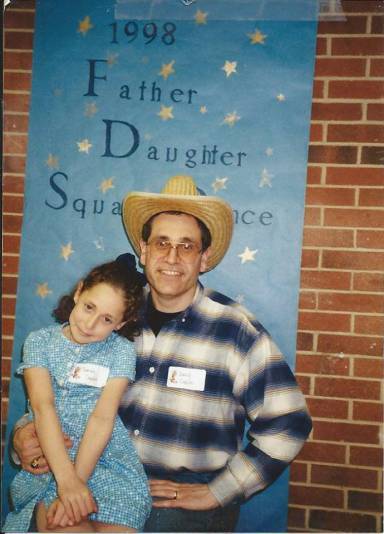

In a world with an alarming number of deadbeat sperm donors, I don’t know why I was blessed to have a dad who taught me how to tie my shoes, ride a bike, drive a stick shift, and quit being so stubborn all the time. Unlike Dad, I don’t believe in good people: but I think my father comes pretty darn close.

I love you, Pop Pops. Thank you for all that you’ve taught me.

(You’re forgiven for never getting me that pony)