“Writing in Ink to Samarkand” by Paul Weimer

You can hear a distant thunder of hoofbeats, steadily growing louder as it approaches. It is a stratum of fantasy that looks beyond the boundary.

You can hear a distant thunder of hoofbeats, steadily growing louder as it approaches. It is a stratum of secondary world fantasy that looks beyond the boundary, the Great Wall of Europe. Secondary world fantasy that is inspired by Byzantium and the Silk Road, all the way to the western borders of China. Characters, landscapes, cultural forms derived from the Abbasid Caliphate, the Taklamakan Desert, and the Empires of Southeast Asia much more than Lancashire.

Thanks to the rising popularity of fantasy fiction, riding, in part, on the wave of Game of Thrones‘ massive success, many of science fiction and fantasy’s old paradigms and forms of have gotten a new look by virtue of new and diverse styles and varieties of stories, new and formerly inhibited voices (primarily women, genderqueer, and minorities), and new or formerly under-utilized wellsprings of inspiration. Elizabeth Bear, one of the many authors at the center of this paradigm shift, calls this “Rainbow SF.” As Science fiction readies its generation ship to move beyond the white-heteronormative-males-conquer-the-galaxy pastiche, popular fantasy is beginning to look beyond the faux-medieval western European that remained so popular throughout the genre’s formative decades. And this doesn’t even include the rise of World SF, as fiction from markets and voices beyond North America and England begin to be heard in the field.

I call such books “Silk Road Fantasy.”

Silk Road Fantasy is hardly a new idea, and can be traced to the works of early 20th century writer Harold Lamb, and even more specifically to Khlit the Wolf, the Cossack, who wanders from China to Russia in the course of his adventures in the 1600s. Stories like “Tal Taluai Khan” set Khilit on the road to adventure, and bring him traveling companions and temporary allies ranging from Afghanistan to China. Most notable of these, Abdul Dost, a Muslim in contrast to Khilit’s Eastern Orthodox Christianity, himself becomes the narrator of several of the stories. Those who champions Lamb’s fiction, like Harold Andrew Jones, have done excellent work in introducing a new generation of readers to these classic, formative novels. However, in my opinion, the real genesis of Silk Road Fantasy as well as the term itself, comes from the works of Susan Shwarz and Judith Tarr.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Schwarz wrote several series of novels exploring the Silk Road. In the Heirs of Byzantium trilogy, an alternate magical Byzantium is the base setting for intrigue and adventure. Empire of the Eagle follows the imagined adventures of the survivors of the defeated Roman Legions of the battle of Carrhae, sent further and further east, far away from the world they knew. Imperial Lady, co-written with Andre Norton, explores the other end of the Silk Road, featuring a former princess of the Han Court as its protagonist, exiled to the steppes. And, notably, Silk Roads and Shadows, the trope namer, wherein a princess of Byzantium heads east in search of the secret of silk.

As wonderful as their work was, Tarr and Schwarz were among only a few lonely voices in a field not yet ready for exploration.

Judith Tarr’s role skews slightly more historical in flavor than Schwarz, and with slightly different interests and locations, focusing on the diversity of Silk Road Fantasy in terms of geography and ethnogeography, and a strong focus on the Crusades. A Wind in Cairo features a protagonist transformed into a stallion during the wars between Saladin and the Christian Crusaders. Similarly, Alamut (and its sequel The Dagger and the Cross) revolve around a prince of Elfland who gets caught up in events like the battle of Hattin and falls for a deathless fire spirit. The cultures, societies and vistas of her Avaryan novels, too, range from the Mediterranean to Tibet in their inspiration and wellsprings.

However, as wonderful as their work was (and still worth tracking down decades later), Tarr and Schwarz were among only a few lonely voices in a field not yet ready for exploration. The ’80s and ’90s were fascinated with faux-medieval worlds — the Four Lands, Midkemia, Osten Ard, and endless celtic fantasy trilogies — meant that the voices drawing on the Silk Road were few and far between. Drowned out. Nearly forgotten.

In the last few years, with the rise of other diversity in fantasy, Silk Road fantasy has returned to prominence. Among the foremost explorers of this long dormant sub-genre is the aforementioned Elizabeth Bear and the Eternal Sky trilogy. In his review of the first volume, Aidan Moher, editor of A Dribble of Ink, said, “Range of Ghosts is wonderful and compelling, a truly great novel that moves the genre forward by challenging and embracing its history all at once.” Bear brings a stunning variety of cultures, terrain,and indelibly memorable characters to Silk Road Fantasy, illustrating the potential for fantasy liberated from the strict terrestrial and historical influences embraced by a large portion of the genre, and fully embracing the potential for secondary world fantasy.

Art by: Frank Hong | Kyu Seok Choi | Daniel Kvasznicza | Alex Tooth

Elizabeth Bear may be the leading light of Silk Road Fantasy, but many others are beside her as she explores a ethnic and geographical history that remains elusive and unknown to many western readers. Mazarkis Williams’ Tower and Knife trilogy borrows on the Middle East and Central Asia in the sensibilities of the Cerani Empire. K.V. Johansen explores the deep, expansive history and mythology of a world inspired by landscapes and peoples of central Asia and Siberia, complete with a trade road that connects them all. Chris Willrich’s second Gaunt and Bone novel, The Silk Map, takes his heroes west out of a China-like realm onto a Central Asian-like deserts and steppe in a poetically intimate story of family in the midst of looming conflicts and events to shape the future of the world, with magical guardians, trade cities, and and airship flying steppe nomads.

As alluring as the idea of fantasy inspired by lands outside Europe is, there is, as always, the danger of cultural appropriation when dealing with cultures, peoples and societies far outside one’s own. Taking merely a veneer or slapdash borrowing of the hard-won heritage of people with a history and concerns of their own is more than just impolite, it’s a real problem. Just as the ’80s and ’90s had a torrent of fantasy novels whose careless borrowings of Celtic mythology and culture frustrate historians and experts in that field, readers must be wary of encouraging Silk Road Fantasy that uses similar appropriations to give its world and air of mysticism and otherliness. Approached with respect, care and careful research, these settings and histories provide wonderful and fresh things for fantasy.

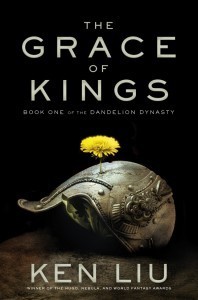

Buy The Grace of Kings by Ken Liu: Book/eBook

Is Silk Road Fantasy the next big thing? Some upcoming releases certainly indicate that its a booming sub-genre of secondary world fantasy. Ken Liu is publishing his first novel, The Grace of Kings, and Elizabeth Bear is working on three more novels set in her Eternal Sky universe. The vast potential of fantasy’s creative potential, Silk Road Fantasy and beyond, remains full of limitless potential. Consider a sword and sorcery novel set in a city inspired by Samarkand, or a secondary world road trip fantasy novel in the vein of Michael Chabon’s Gentlemen of the Road. How about more novels that are inspired by the Mongols, the Tibetan Empire, the shamans of the Siberian steppe, the Moghuls, and others along the branches of that fabled trade route. I look forward to many other writers exploring the Silk Road, with careful respect and care to the source cultures, and writing in ink to Samarkand.

The post “Writing in Ink to Samarkand” by Paul Weimer appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.