Mortality Strikes Again

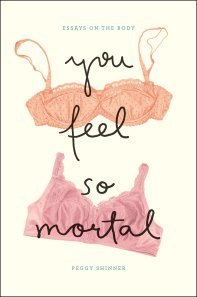

YOU FEEL SO MORTAL: ESSAYS ON THE BODY by Peggy Shinner

YOU FEEL SO MORTAL: ESSAYS ON THE BODY by Peggy Shinner

I’m so fucking glad University of Chicago Press finally published a collection of Peggy Shinner’s essays on the body. Except, though, I’m not glad it got published, like, in Chicago, for whatever reason (I don’t pretend I know the politics of this stuff), only because Shinner’s already a local legend and I need people outside this city to realize THIS LADY’S A LEGEND.

I love this book. You’ll love this book if you’ve ever looked at even one part of your body and thought why the fuck are you like that, or had trouble understanding even one idiosyncrasy of the particular brain inside you. God, these essays are so fucking fantastic, I greedily read them all in a day (even though, in reality, they’ve been parceled out, appearing in lit mags as earlier as 2000) and just KNOW I’ll be digesting them for a long long while to come.

As mentioned, every essay in here is unapologetically centered around the body. Of course, we springboard from there. Pieces about posture become about race in America; thoughts on autopsies summon religious beliefs; nose jobs relate into a man’s ability to function at a peak professional level.

Shinner, an outsider from the American ideal in many ways (Jewish, woman, lesbian), struggles with the way her body, this misshapen Jewish body of hers, fits into the larger context of the world in many essays.

Here are parts of her she feels oddly about and contributes to her race: Feet; posture; nose; inability to face cremation; unease with organ donation.

Here are parts of her she feels oddly about and contributes to being a woman: a tinge of kleptomania; decreased ability to defend herself; breasts; hair.

Here are parts of her she feels oddly about and contributes to her brain: desperation to feel unique; discomfort with being mildly depressed; being a lesbian; guilt about feeling oddly about her Jewish qualities; guilt about feeling oddly about her womanish qualities.

These stories, though, are amazing.

“Pocketing” reveals what I’ve always thought to be true, but never asked my friends: Don’t you just get the urge to steal things you could very well buy? Shinner’s stolen a few things from stores, something I’ve never been brave enough to do; any pocketing of mine has been from friends and families homes, which is probably worse. I only steal tiny tiny things, items I can put in a pocket like beads, trinkets or miniature figurines, sample squirt bottles of perfume, a perfect lipstick. Of course, once these items make it back to my house, I’m too guilty to ever touch them, never able to use or look at the objects, and then I go on beating myself up over taking the thing. What Shinner confirms: I am not insane for doing this. In fact, someone reading this is probably nodding her head (because it’s likely a woman) in agreement. Unlike some experts believe, kleptomania is not a sexual fetish; it’s an impulse-control issue. Much like picking a scab, we know it will never end well, but we must do it nonetheless.

“Berenice’s Hair” may be my favorite piece, despite it’s subdued, third-person tones. Tracing the mythologies and the rules surrounding womens’ hair for thousands of years, Shinner offers no advice on how to keep one locks, only a reiteration of what society has always told us. There is no telling who is right who is wrong; it’s plainly laid before us without comment.

“Postmortem,” the conclusion of the book, sees Shinner struggling to come to terms with the science and cultural significance of her father’s autopsy. When first asked if they elect for the procedure, she and her family accept. A funeral is had, and weeks later, Shinner learns doctors are still examining her father’s brain. Because it wasn’t buried inside him. None of his organs were. That’s just how autopsies are. But it’s funny – wouldn’t we know that? Why does that seem like new information? Do we hear that, nod, and promptly forgot because it’s too strange to imagine our skin, dressed in suits and silk dresses, going into the earth empty not just of soul, but of, really, all substance?

Maybe that’s what I love about You Feel So Mortal the most. Shinner raises these questions, probes around her own world, her own body, yet puts no judgment on ours. She does not dismiss you for having a nose job. She does not roll her eyes at your rock hard abs, posture of a princess. She looks at these fleshy, mortal bodies, realizes the fragility of these objects and does nothing to injury the spirit inside. Instead, we are only asked to wonder.