Ithaca and What's Next

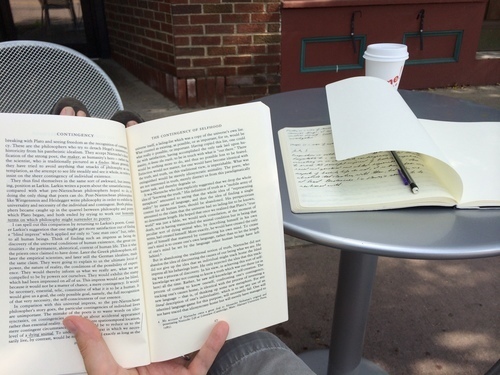

Back in Ithaca, my intellectual hometown, the last place I was a student, pretending to be a student, outside the Gimme! Coffee on State Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Street) where I wrote most of my dissertation, on sabbatical, smelling cigarettes, feeling the in-betweenness of things. Reading books I found at the used bookstore owned by my former employer Jack Goldman, who's still kind enough to give me an employee discount: Richard Rorty's Contingency, irony, and solidarity, John Dewey's Experience and Nature, Ann Charters's strange 1968 monograph on Olson and Melville. Also carrying around Hannah Arendt's The Human Condition, Hilda Hilst's With My Dog-Eyes, Ernst Meister's haunting In Time's Rift, as translated by Graham Foust and Samuel Frederick (Sam was in the Finnegans Wake reading group I belonged to in my Cornell days, so that's another fragment of my Ithaca past).

Reading, and writing, though most of the writing is gathered from old notebooks (a phrase I'll forever associate with Evan Lavender-Smith's novel). Trying to pitch things forward. My first novel has been officially out for a month now: I'm grateful for the favorable notices it's received (here and here and here, and also here) but as always in my experience publishing a book is like dropping a radio-controlled model submarine in a pond: you let the thing go, you wiggle some levers and give the remote a shake now and then, but you have no idea if it's getting anywhere or has run aground or if anyone else has noticed the slight ripple in the algae-strewn waters of literature.

A book needs readers to live. Yet the essential work has been done: devoting three-plus years to writing a novel has changed me and my sense of what's possible. Rorty reminds me that the self is not "out there" or "in there" to be discovered: it is made, formed, by successive interventions and descriptions. Am I a novelist? The question is a bad habit I need to let go. In his very flattering review, R. Alan Clanton calls my novel "a 369-page-long poem," and "a hundred long-form poems compressed deftly into the singularity known as the novel." Implying that the novel in its density is a kind of dwarf star or black hole; I think of Lorine Niedecker's phrase, "this condensery." Apparently there is no layoff for me from the condensery of poetry: I wrote prose and Clanton calls it poetry. Habit, destiny, choice? I wrote a novel in good faith, I think, one of the kinds of novel that I like to read: dense, poetic, baring its devices, questioning the possibility of storytelling as its means of telling a story. My models and influences were European, or inflected by the European: Calvino, Bolaño, Woolf, Saramago, James. The novel is not about a poet but a "new reader," who through obsessive reading of novels and poems and her mother's letters falls into fantasy, into the novel that contains her, a detective story, an attempt at redescribing history (a personal history of the twentieth century, its traumas and echoes) so as to redescribe herself. To return to the middle of things, in medias res, to life, in and through fantasy, reading and writing.

What comes next? If you're a reader of mine it's The Barons, my fourth poetry collection, coming in October from Omnidawn. It's a book of outrage, wrestling with epic, offering a different kind of resistance to the dead descriptions that chain us to the dead century we just can't seem to quit: echoes of the cold war, of the most violent and primitive forms of religiosity and tribalism, scaled horrifyingly upward by the capabilities of modern media and the modern state, themselves teetering on the brink of unimaginable transformation. I am writing my way forward, trying to find a language of the Anthropocene. The Barons is the first book in a projected trilogy that includes two manuscripts in progress: The Spoils, confronting revenant ideologies with the vitality of materialism, and an as-yet untitled project in which replicants of Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger struggle with each other against an apocalyptic twenty-first century backdrop. It's tempting to call the latter a novel, but in writing it feels closer to theater or gladiatorial combat.

Mixed up in all of this, elusively, the personal. Almost all of my writing, in any form, has had the properties and intention of exorcism: my mother, more than twenty years gone, is the beautiful soul I evade and appease and elegize. Foolish to pretend such exorcisms are ever completely successful. She is the twentieth-century ghost that haunts me, whose life I try to expiate and describe and re-live. If her form is difficult to discern in my current projects that indicates only my own blindness, a secret constraint (Brian Eno: "Any constraint is part of the skeleton that you build the composition on--including your own incompetence"). I conceal from myself what I reveal to others, and vice-versa. Writing is a strange form of keeping faith, like any heresy.

Other projects and possibilities smolder just out of sight: short fictions and parables, poems that read like essays, a novel that's less novel, further engagements with Olson and Duncan and Creeley and Howe. I think about the vision of pragmatism, the powerful potential of the made-up to transform what we take being. I write, and erase. I circle back "home" to Ithaca and launch myself outward again on a spiral, I hope, of surprise. "I hunt among stones."