BE IT EVER SO HUMBLE: LIFE IN EAST HAMPTON, THEN AND NOW

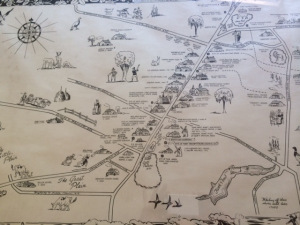

Map in my possession showing the village on its 300th anniversary, 1948

It’s a source of some amusement to me that John Howard Payne, lyricist of the immortal ‘Home Sweet Home’ (“Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home…”) spent his youth in East Hampton. In fact, the small colonial residence of his grandfather, where he lived, is now a museum, sitting on Main St. amongst a line of colonial and Victorian properties. But East Hampton is hardly known for its history. Programs such as ‘Royal Pains’ and ‘Revenge’ as well as a plethora of films, including ‘Something’s Gotta Give,’ continue to perpetuate the image of ‘The Hamptons’ as the enclave of the rich and famous. That’s hardly true of the entire population! And it certainly wasn’t always true…

As with all of the Americas, indigenous peoples were present long before European settlers made an appearance. The locals then were a part of the Algonquin nation, generally called Montauketts. In the late 17th Century, Puritan and other colonists from Connecticut moved down to the Long Island area. A smaller island off shore was sold to one Lion Gardiner for a large black dog, some powder with shot, and a few Dutch blankets. Today the taxes alone on the island are purported to be over 2 million dollars…and the island continues to be owned by descendants of the Gardiner family. In any event, Gardiner’s Island was the first English settlement in what became New York.

Gardiner built a second home, in what is now East Hampton, in 1654.

Mulford Farm, now on The National Register of Historic Places

Earlier, in 1640, Puritan families had moved down from Massachusetts to the Southampton area, escaping strict laws and seeking more land, and had migrated east to what they then called Maidstone in 1649. They signed a treaty with both the Montaukett and Shinnecock peoples, buying the land for 20 coats, 24 looking glasses, 24 hatchetts, 24 knives, 24 hoes and 100 “muxes.” They then secured a patent or colonial charter from Governor Richard Nicholls in 1666. The village of East Hampton subsequently developed from 34 allottments of 8 to 10 acres since life here in the colonial period was based on farming. Note that the town and the village are 2 distinct entities; today, East Hampton Town includes the villages of Wainscott, part of Sag Harbor, East Hampton, Napeague, Amagansett and Springs.

The main government during the colonial period was the town council. The town records give some idea of the concerns of the people:

“November 27 agreed that the Indians shall cut no wood nor timber nor live in…field.”

“1756 October 27 The Trustees did then chuse, nominate and appoint John Dayton by mager vot for to sue, prosecute and recover the damage the Town shall or may receive from any person that shall at aney time presume to hunt after Deere or fowl in the Town ship of Easthampton the person not being…an inhabitant of said town.” (sic)

“Novem 9th agreed with ye Indians for to tak up with Seven pounds for the damage their hogs had don in rooting up ye land…” (sic)

There is also a list of charges to the Town, such as “1733 to Ichabod Leek for warning ye trustees 1’6” –though no mention is made of what he was warning them about!

1770 House, now a restaurant

During the Revolution, the village was occupied by the British from 1776 to 1783. Various myths and stories come out of this period but my favorite is that in 1776 a “certain Stirring Dame” of East Hampton threw a hot pudding filled with berries at a foraging party of British soldiers. The site of this incident is still known as “Pudding Hill.” My own street, Whooping Hollow Rd., also has an interesting legend: originally called, “Whooping Boy’s Hollow,” it tells of an Indian boy who was scalped on the road by hostile Indians. His whooping spirit still supposedly haunts the area.

Over the years, the region developed as a farming, fishing and whaling community. Working class families moved into Springs (never use “the”!) and were called by the name of Bonnackers, referring to the fact that Springs is on Accabonac Harbor. They have their own dialect, now mostly softened by the New York infiltration, which developed from 17th C England. Sadly, the local fishing industry, which was their main occupation, has dwindled, and many now work in various fields related to tourism, while Springs also supports a large Latino community.

Original colonial house

So when did the rich and famous move in? In the late 19th century Southampton proved a draw for the wealthy of the Gilded Age and is still known as the Hampton of ‘old money.’ It’s streets have signs protesting against wearing bathing suits in town, and an elegance of a by-gone era still exists in the old mansions that line the shore. East Hampton remained largely rural until the railroad came in 1880. When the Maidstone Club was built in 1891, the wealthy came along; to this day, membership is extremely difficult to obtain. East Hampton drew a more artsy crowd in the 1950s when artists such as Jackson Pollock, whose house is open to the public, and buddies like Warhol, Motherwell, Kline and so on came out to work in the peace and quiet of the countryside. And so, East Hampton developed as the Hampton of the celebrities, with the Artists and Writers’ baseball game a highlight of the summer season. I’ve gone through a door with Catherine Zeta Jones while Michael Douglas looked on, been in restaurants while Salman Rushdie, Martha Stewart, Gabriel Byrne or Renee Zellwegger dined nearby, shopped when Alec Baldwin has popped in, attended a benefit basketball game with Jay-Z, and stood outside the movie house with Steven Spielberg, with whom I’ve also exchanged a few words while canoeing out on Georgica Pond. Charity events go on throughout the summer as do art and antique shows, theatre, church fairs and readings by well known authors. Polo is played and The Hampton Classic Horse Show is a major event. And these days, the Town Council deals with a mixed population in a growing community, while trying to maintain the rural atmosphere of a town with very limited land, caught as it is between Long Island Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. The Ladies Village Improvement Society (known as LVIS) keeps a stern eye on any change not consistent with the historic setting.

As quite an ordinary person I feel lucky to live here.

East Hampton Library

The library is unlike most libraries, having been built rather like a Tudor home complete with grand staircase and sitting area by a fire. The two windmills and other historic buildings are beautifully kept, as is the old cemetery near the village pond. It’s a beautiful village in which to live. Yet when I bought my home, 16 years ago,  the village had lovely little ‘Mom and Pop’ stores and was relatively uncrowded after Labor Day. Nowadays the village is given over to stores the likes of Gucci, Tiffany, Ralph Lauren and Hermes, as if someone might have a handbag emergency—and they mostly close down for the winter months. The beaches are public but parking there is not; residents have to obtain permits with identity to show they live here, and there is a strict division between town beaches and village beaches, depending on where you live. Restaurants go in and out of fashion and in and out of business in the twinkling of an eye. The general aura is that the summer visitors matter the most.

the village had lovely little ‘Mom and Pop’ stores and was relatively uncrowded after Labor Day. Nowadays the village is given over to stores the likes of Gucci, Tiffany, Ralph Lauren and Hermes, as if someone might have a handbag emergency—and they mostly close down for the winter months. The beaches are public but parking there is not; residents have to obtain permits with identity to show they live here, and there is a strict division between town beaches and village beaches, depending on where you live. Restaurants go in and out of fashion and in and out of business in the twinkling of an eye. The general aura is that the summer visitors matter the most.

In my forthcoming book, Dances of the Heart, East Hampton is portrayed in the way most people think of it, a glitzy summer resort, home of the wealthy. But that said, my own preference is to be here in the late autumn or early spring when the weather is good but the crowds are gone—and the only thing to contend with are those descendants of the ‘Deere and fowl’—mainly wild turkeys—that the settlers didn’t want shot.

(One final note to my western readers: John Howard Payne eventually lived with the Cherokee, coming to a theory that they were the lost tribe of Israel…)