“No Greater Calling” Total Indian War Guide

Eric Johnson, thanks for the interview. I’m so impressed by your book, No Greater Calling. You’ve provided something I’ve never seen before, a comprehensive guide to the Western Indian Wars.

Eric Johnson, thanks for the interview. I’m so impressed by your book, No Greater Calling. You’ve provided something I’ve never seen before, a comprehensive guide to the Western Indian Wars.Readers, Eric has provided the date and place for every hostile encounter between tribal warriors and the U.S. Army (1,400) that occurred between 1865 and 1898, plus the number of men killed and wounded, their names and the kind of wounds the men sustained.

Some of the reports include information on the battle and the names of men who earned promotions due to their conduct on the field. Medal of Honor winners are also included.

Medal of Honor: 1862-1896

Medal of Honor: 1862-1896Q. What inspired you to write this book?

A. Of all that I’ve done in life, I am most proud of the time I spent in service to this nation in the United States Navy, having served nearly six years between 1985 and 1990.

As a veteran, I truly believe that all those who answer their nation’s greatest call deserve being honored, they deserve the simple dignity of having their names remembered.

I believe this to be the case regardless of the pursuits that placed these men in harm’s way, regardless of who these men were.

I hope in some small measure my work restores these men that dignity!

Post-Navy Eric, with his father

Post-Navy Eric, with his father

Q. Can you tell us where you got your information and how you put it together?

A. Early on, I had a vision of what I wanted to accomplish, that being to list the names of those men killed in action. Everything else was added as I continued my research!

The Adjutant Generals Chronological List provided me a frame around which to build my data. To that, I cross-referenced Francis Heitman’s Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army and Record of Engagements with Hostile Indians within the Military Division of the Missouri.

And finally, I further cross-referenced the resulting list to the Annual Reports of the War Department and, to a lesser degree, Indian Affairs.

Now that I had my list, a framework around which to frame my data, I had to fill in the names of those killed, and later wounded, in action.

This involved a total of three trips to the U.S. National Archives.

My primary source in providing names were individual files in Report of Diseases and Individual Cases or F-Files.

Also helpful were the Registers of Army Dead, a number of large volumes in which were alphabetically listed the names of Army dead for a certain period.

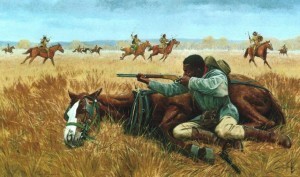

by Frederic Remington

by Frederic RemingtonThe F-Files were the reports filed by the attached medical officer immediately following the fight.

There’s a certain power in reviewing these documents, wondering about the condition of those filing these reports. Were they exhausted, having spent hours treating the wounded?

Finally, I tried to list one or more Secondary Sources for each fight…from both the Public Library and The Ohio State University Library in Columbus, Ohio.

I will say I am very, very proud of what I accomplished.

Q. Is it possible to estimate how many died of their wounds?

A. An accurate answer would require studying the carded medical files, a study involving countless hours at the National Archives.

Reno defense site, where more than sixty were wounded.

Reno defense site, where more than sixty were wounded.

That said…At Little Big Horn, the Reno defense site, sixty-five were wounded. I was only able to identify four who died of their wounds; Private William George on July 3, Private James Bennett on July 5, Private David Cooney on July 20 and Private Frank Braun on October 4.

During the Modoc War, of which I write more below, in a disastrous fight at Hardin Butte on April 26, 1873, twenty men were wounded.

Fortifications leading to Hardin Butte

Fortifications leading to Hardin Butte

I was able to identify three who later died; Private William Denham on May 6, 1st Lieutenant George Harris (who lived long enough for his mother to travel from Philadelphia to be at his side when he died on May 12), and First Sergeant Malachi Clinton on June 14.

And finally, during the Nez Perce War, thirty-eight men were wounded on August 9 and 10, 1877, near the Big Hole Basin, Montana Territory.

Big Hole Valley This battle became the turning point for the Nez Perce.

Big Hole Valley This battle became the turning point for the Nez Perce.

I identified two who died of their wounds; Sergeant William Watson on August 29 and 1st Lieutenant William English on September 19.

So, I look at three fights, a truly limited sample size. One hundred and twenty-three men were wounded and nine later died of their wounds. Just over seven percent?

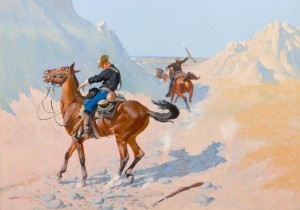

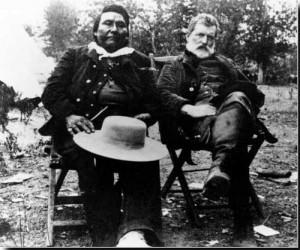

Chief Joseph and Col. John Gibbon met again on the Big Hole Battlefield site in 1889.

Chief Joseph and Col. John Gibbon met again on the Big Hole Battlefield site in 1889.Even harder to represent are those who died of their wounds several months or even years later.

One such soldier was 2nd Lieutenant Franklin Yeaton, wounded by Apache Indians on December 26, 1869. He died nearly three years later on August 17, 1872. His obituary states his death was the result of that wound.

Should I have included him? I did not. Earlier versions did. If my publisher ever tasks me to do a second edition, perhaps I will include him again!

Q. Did you come to some personal conclusions about the Indian Wars and the Army by compiling the information?

A. I went into No Greater Calling with the belief that the Indian Wars were the inevitable result of the meeting of two cultures which little understood, and even less respected, each other. I have found nothing to make me believe anything different.

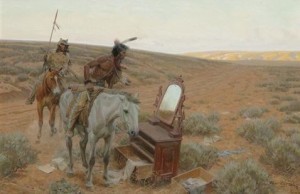

The Heirloom, by Tom Lovell

The Heirloom, by Tom Lovell

By 1865, the end of the American Civil War, Indians could be pushed no further West. And nothing was going to stop the Western movement of those, tired of war, seeking new life and new opportunities in that same West.

Recent scholarship has tended to focus upon the costs suffered by Native Americans. In some small measure, I hope my work demonstrates that many suffered, soldier, settler and Indian!

Sioux weapons

Sioux weapons

Q. In the beginning, in the mid-1860’s, many soldiers were wounded by bows and arrows. Then that began changing in the 1870’s and most of the wounded were shot. What did you conclude from that?

A. I did notice that. Earlier research included the number wounded by arrow versus gunshot. It is very apparent, especially on the Plains, that guns were becoming more and more available with the passage of time.

That said, I’m afraid drawing any statistical conclusion is to be approached with great care.

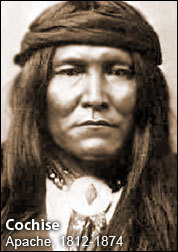

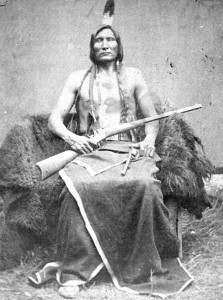

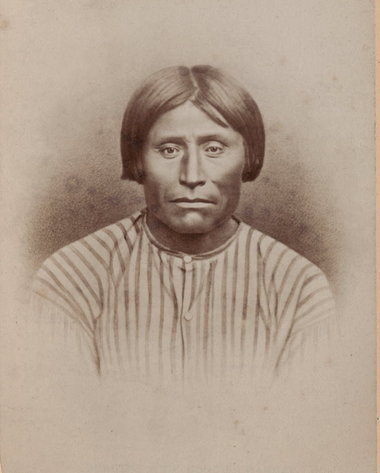

Touch the Clouds, a Sioux, 1877

Touch the Clouds, a Sioux, 1877

The number of Army wounded is skewed downward. For example, there were no wounded who rode with Custer, but I have read Indians used the bow to great effect at LBH.

Q. I was startled by how many skirmishes, actions and battles occurred in Kansas. Can you explain why Kansas seemed to be such a constant battleground?

A. Kansas was quite literally at the crossroads of the nation. There were more settlers, more citizens, more men laying tracks, and more surveyors, consequently there was more contact and more violence.

Laying tracks in Nevada, in 1869

Laying tracks in Nevada, in 1869

Among those Indians involved in open warfare against encroaching civilization, in Kansas, were the Cheyenne, the Comanche, the Kiowa, the Lakota, and the Pawnee.

The earliest fights on the Plains involving the Army and Indians were in Kansas in the late 1850’s.

On July 29, 1857, Colonel Edwin Sumner led a command against Cheyenne Indians near Solomon’s Fork, Kanas.

The final Indian vs. Army fight in Kansas occurred near Punished Woman’s Fork on September 27, 1878.

Punished Woman’s Fork, site of one of the last battles between the Cheyenne and the U.S. Cavalry. The women and children hid in this cave.

Punished Woman’s Fork, site of one of the last battles between the Cheyenne and the U.S. Cavalry. The women and children hid in this cave.Lt. Colonel William Lewis was mortally wounded in this fight, bleeding to death the next day. He was the third highest officer killed during the Indian Wars and the last Army casualty in Kansas in a fight with Indians.

Q. You’ve noted citizen deaths in the books. But there seemed to be many more citizen deaths than were reported to the Army (at least in Texas). Is that right?

A. That is most certainly right. No Greater Calling evolved over the decade I worked on it. An earlier version was a very much a defense of “Why we fight.”

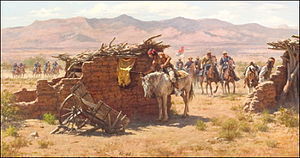

Search for the Renegades, by Howard Terpning

Search for the Renegades, by Howard Terpning

I believe many of the conditions in the West necessitated a military response. So early on I provided a lot more focus on citizens killed.

In it, I listed several hundred citizen casualties which were eventually deleted.

Also, the quotes I interspaced throughout my list tended to focus on Indian brutality.

But at some point I decided the tone of my work was becoming decidedly anti-Indian, which was not my intention.

It’s meant to be a celebration of the Frontier Army, not a damning of the Indian.

There was no monopoly by either the Army or Indians in brutality! I hope the difference is not lost.

So the civilian vs Indian casualties were limited to those listed on the previously mentioned Chronological List.

I will say this, there are several Indian vs. citizen fights which I left out only with great hesitation.

Two that come immediately to mind were both in Texas, the death of Britt Johnson in 1871 and the murder of the German Family in 1874.

Britt Johnson’s last stand against the Kiowa. Painting by Lee Herring.

Britt Johnson’s last stand against the Kiowa. Painting by Lee Herring.

Q. What did you consider the most interesting encounter between hostiles and the Army?

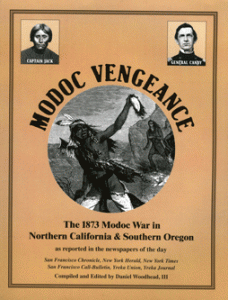

A. The most interesting? I suppose if I needed to select one campaign it would be the Modoc War.

It was so different from most of the Army vs. the Indian battles, the Army laying siege to an entrenched Indian (position), one of the only campaigns in which artillery played a role.

It was also during the Modoc War in which the only Indian Wars’ general, Edward Canby, was killed–George Custer wearing the rank of Lt. Colonel at the time of his death.

Q. Can you tell us about the Modoc War?

A. In late 1872, a decision was made to move a small band of Modoc Indians, led by headsman Captain Jack, back to a Klamath Indian reservation (which they had previously fled). This was done with little regard for the Modoc’s history, their culture or most importantly their wishes. The Klamath Indians were the Modoc’s traditional foe.

Captain Jack

Captain Jack

A band of 1st U.S. Cavalrymen under the command of Captain James Jackson was sent to expedite this move.

Arriving at the Modoc village near Lost River, Oregon, words, and then gunfire, were exchanged.

Two cavalrymen were killed, several others wounded.

The Modocs fled across Tule Lake to a natural fortress at the Lava Beds, but not before first killing several local ranchers.

Captain Jack’s cave, at the Lava Beds

Captain Jack’s cave, at the Lava Beds

The Army responded, first the 1st U.S. Cavalry and later the 21st U.S. Infantry, the 4th U.S. Artillery and local volunteers of Oregon and California.

Very quickly, the fight became a siege. This in itself made it unique among the campaigns of the Indian Wars.

The Modoc War was also among the first of the Indian Wars the press heavily covered. Initially, this coverage was heavily in favor of the Modocs.

On January 17, 1873, the first attempt was made to (take) the Modoc position, with the Army being forced back with heavy losses.

In response to the disaster, General Edward Canby, Commanding the Department of Columbia, arrived to take command.

Q. How was Canby killed?

A. General Edward R.S. Canby was by any measure a warrior, spending his entire life in service to his nation, but he gave his life in a quest for peace.

In April 1873, Canby, accompanied by the Reverend Eleasar Thomas and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Alfred Meacham, agreed to meet with Captain Jack and a party of Modocs.

The murder of Canby

The murder of Canby

It was hoped (Canby) could bring the war to an end and that many lives, both soldier and Indian might be saved.

Instead, on April 11, the Modocs sprang on Canby and his unarmed party. Canby and Thomas were murdered; Meacham was grievously wounded and was not expected to survive.

It has been proposed the Modocs believed that the death of Canby would force the Army to “go home.” It did not.

Modoc, probably staged following the war

Modoc, probably staged following the war

Instead, what was viewed as Modoc treachery, assured the carrying out of the war to its end. The coverage in the press, which had been so positive, took a decided turn against the Modocs.

By late April, the natural fort at the Lava Beds was carried, and by late May, Captain Jack and his followers were forced to surrender.

For his crimes, Captain Jack was hanged (with some of his men). His Modoc followers were sent to a reservation in faraway Indian Territory, modern day Oklahoma.

Captain Jack’s grave

Captain Jack’s grave

Q. Did you attempt to discover the particulars on any given encounter?

A. I enjoyed learning about Caspar Collins and the Battle of the Platte Bridge.

It was due to young Lieutenant Collins that I began No Greater Calling in 1865 and not 1866, the year the Army considers the start of the Indian Wars.

Twice I have spoken on my work. Each time Collins was the primary focus of my presentation.

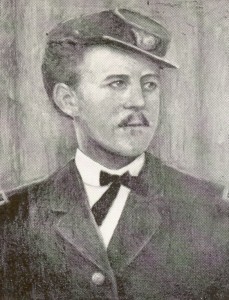

Portrait-of-Caspar-Collins-painted-by-Ruth-Joy-Hopkins-

Portrait-of-Caspar-Collins-painted-by-Ruth-Joy-Hopkins-

On the final day of his life, 2nd Lieutenant Caspar Collins, himself the son of regimental Colonel William Collins, found himself at the Platte River Bridge Station, on his way to rejoin the 11th Ohio Cavalry at the Sweetwater Station to the West.

While there, Collins was ordered to lead a detachment of 11th Kansas Cavalrymen, to relieve an approaching military wagon train.

A fellow Ohio officer begged Collins not to go, as this was not his task, to which Collins responded, “I know what it means to go out…but I’ve never disobeyed an order. I’m a soldier’s son.”

Statue of Casper Collins

Statue of Casper Collins

And so Caspar Collins, resplendent in his newly purchased uniform, riding a borrowed horse, a borrowed revolver tucked into each boot, formed his small command.

Before riding out, he stopped, passing his kepi to another soldier, remarking, “I will not return.”

(After) riding from the station and turning west, an overwhelming number of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors sprang on Collins and his small command.

Seizing the situation, Collins ordered his men towards the sanctuary of the bridge.

Collins, himself wounded, paused to help a fallen trooper onto his horse, only to be overwhelmed by pursuing Indians.

Caspar Collins and four others of his command were killed, nine others wounded. Collins’ horribly mutilated remains were recovered the next day, and buried at the station cemetery.

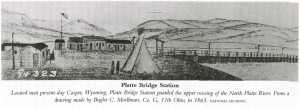

The Platte River Station was renamed Fort Caspar, around which would grow Casper, Wyoming, today the second largest city in Wyoming.

Fort Casper

Fort Casper

Q. What attracted you to Collins?

A. He was from Ohio. His remains were shipped home to Ohio in 1866 and he is buried only an hour from my home.

The escorting of his remains to Columbus, and then on to Hillsboro, was the last duty the men of the 11th Ohio Cavalry performed, and they were the last of the Ohio regiments to be mustered out.

When I read the story of his death, I couldn’t help but be impressed. He was a hero.

He was only twenty years old, a fact not uncommon during the American Civil War, but as he rode to his death, as he rode upon what his grave marker refers to as a forlorn hope, he did so with such poise, such bravery.

As I read about these men, I asked myself, could I do the same?

Following his death, General Grenville Dodge wrote to Caspar’s grieving parents… “Your noble and gallant son… furnishes by his brave conduct a bight example for heroism to the county and to my command.”

Truly powerful words, words I wish I might have written… “A bright example for heroism to the country…”

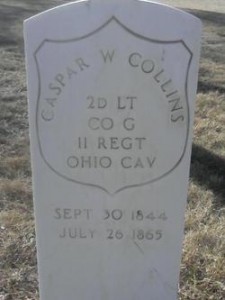

While working on No Greater Calling I traveled to Hillsboro, Ohio to take a picture of Collins’ grave. I visited his boyhood home, which still stands as a private residence on Collins Lane.

On the way home, I stopped at a small diner, only a mile from his grave, a mile from his home.

Casper Collins’ grave

While making small talk with a dozen other diners, I mentioned why I was there: “I’m an historian traveling from Columbus, Ohio to take a picture of the grave of Caspar Collins.”

Some of them were old and some young. While I’m sure they were all impressed to be having lunch with a real, live historian, none of them had ever heard of Caspar Collins.

“A bright example for heroism to the country…” And here, a dozen in his own hometown had never heard of him. Heartbreaking!

My dream is that in some small way, my work can make sure Caspar Collins and 1,100 others are remembered.

That’s my ultimate goal with No Greater Calling. I never wanted this work to be about me. Instead I wanted it to be about the frontier soldier.

Q. Did you ever get the chills while doing research?

A. Those things that most affected me were the grave pictures: The passing of an entire life, the only evidence of which remains a simple stone marker. There is something profoundly sad about that!

And I confess to shedding a few tears as I looked upon them.

Almy

Almy

There is 5th U.S. Cavalryman Jacob Almy’s grave. Almy, a veteran of the American Civil War and the son of Quakers, was a graduate of West Point.

He was murdered by an Apache Indian, on the San Carlos Reservation, on May 27, 1873. His marker is utterly illegible, identified only by the numbered plaque beside it.

Howard Cushing is the third of the famed Cushing brothers. While his brothers are buried at West Point and the U.S. Naval Academy cemeteries, Cushing’s grave is in San Francisco. He is buried so far from home, so far from the place of his death. His name is misspelled on his marker.

Finally, there is Albion Howe’s grave. Howe, the nephew of General Albion Howe, was killed during the Modoc War, in 1873.

His wife, Sarah, spent nearly forty years mourning her husband before joining him in death in 1912.

Each marker tells a small part of that man’s story.

The graves of those I could not discover, those are the ones I take with me each night when I close my eyes.

Q. What are you working on now?

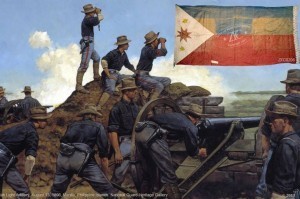

Fighting in the Philippines

A. Right now I am a few months into the same study, but this one devoted to the Philippine Insurrection fought between 1899 and 1902.

My Father likes to ask when this one will be done. I figure I spent ten years on No Greater Calling; I’d like to have the follow-up done in five.

The Philippines is interesting because I knew so little about it. And the number of secondary sources is much more limited.

Beyond that, a study of the Spanish American War and a study of the “Little Wars” of the era.

An associate of mine, after first seeing No Greater Calling, stated I might be the greatest advocate of the frontier Army since John Ford.

If that is to be my obituary, I think I can live with that!

The post appeared first on Julia Robb, Novelist.

Published on June 27, 2014 14:59

No comments have been added yet.