Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’ by Shana L. Redmond

Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’

by Shana L. Redmond | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

Ladies Night: Review of ‘Think Like a Man Too’

by Shana L. Redmond | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)I have never seriously considered thinking like a man. Beyond a rejection of the homogeneity embedded within the demand that I think like a man (read: any man) and a recognition that your definition of “man” and mine may be very different, I also question the suggestion that the act of thinking like a man is at all beneficial. Don’t get me wrong; I rely on the thoughts of thoughtful men every single day. For example, I truly, hand to heart, believe Harry Belafonte (a man) when he sings, “man smart, woman smarter.” I even sing along (loudly). Some of my best friends are men (to whom I listen on occasion). My refusal to think like a man stems then not from any dislike for the way that certain men think but from the simple truth that I like the way that I think better.

Of course, I recognize that most women are not socialized this way and wider society reflects the reasons why. As majority (if not exclusively) male state and federal committees continue to debate and legislate women’s health, including abortion and contraception, we are similarly faced with a popular culture that tells women who and what we are, when and where we should be, and why we should be grateful for the limited access and representation that we receive. The premise of the Think Like a Man (TLAM) franchise—composed of a best-selling book by comedian Steve Harvey and two major film releases by director Tim Story—follows in this logic by telling Black women, in particular, that our capacity for rigorous and strategic thought is limited, flawed, and, ultimately, disadvantageous in our efforts to attract and keep not just Black men, but any men.

Though ripe for the picking, I’m going to forgo engagement with debates of Enlightenment thought and rationality as a colonial enterprise; I do, however, want to note just a couple of the more apparent and pressing concerns of these productions as they are the common sense of the films’ influence. TLAM & Think Like a Man Too (TLAMToo) suggest that Black women—as a monolith—are singularly motivated by our primordial instinct to mate and nest with the male species, which additionally assumes that we are basic heterosexuals—monogamous and unqueer. TLAMToo even uses prison scenes—for both the men and the women—to announce (without provocation) the characters’ proximity to but repudiation of homosexuality. Both films also suggest that for women, emotions can be our strength but are most often our weakness, requiring that we be trained to thinkin a particular, even singular, way. This was an especially prominent storyline within the original film.

The Achilles heel of the beautiful, hyper-professional business mogul Lauren (Taraji P. Henson) in TLAM was her stubborness, which nearly ended her relationship with the gorgeous and underemployed chef Dominic (Michael Ealy). By the end of the film, she is the final hurdle that the rom-com must overcome; her display of conciliation at the very end of the film, in full view of their friends and his food truck patrons, shows that the game of love is a tactical one that requires women to lose in order to win.

Men clearly have home court advantage in both films; the very lexicon of the game solidifies the films’ placement within a sphere of male dominance, even as women’s characterizations mature in the sequel. Though the game metaphors continue in TLAMToo—women and men are on “opposite teams,” the men commit “turnovers” that leave them vulnerable to the women, and, at some point, all characters find the “score tied”—the strategy in the “battle of the [two] sexes” was underplayed this time around. Gone is Harvey’s installment as an ‘impartial’ referee who reminds the audience of the rules of engagement. TLAMToo instead shows us what the characters have learned as all five couples, plus a solo Cedric (Kevin Hart) and Sonia (La La Anthony), travel to Las Vegas for the wedding of Candace (Regina Hall) and Michael (Terrence J).

Like The Best Man (1999) before it, the film does not privilege the nuptials—it instead develops an escalation of raucous scenes drawn from the bachelor and bachelorette parties. Beginning with a reprise of Tom Cruise’s famous Risky Business scene by Cedric in his posh hotel suite and “high tea” for Candace (complete with a deflated “Idris” blow-up doll) planned by Michael’s disapproving mother Loretta (Jenifer Lewis), the inevitable comedy of errors leads to consistent laughs built from Hart’s spot-on exaggeration and timing as well as the ensemble cast’s ability to reference and reinvent defining Black popular culture moments of our generation.

By losing Harvey and formal ties to his book, TLAMTooprovides more space for the women—this time joined by Tish (Wendi McClendon-Covey), the dowdy wife of Bennett (Gary Owen)—to determine their pleasure, no matter how cliché. They are the ones who most thoroughly develop the audience’s tie to the Black popular culture of the past, in the process breaking the fourth wall and provoking the head nods, applause, and call and response that only comes from mutual recognition.

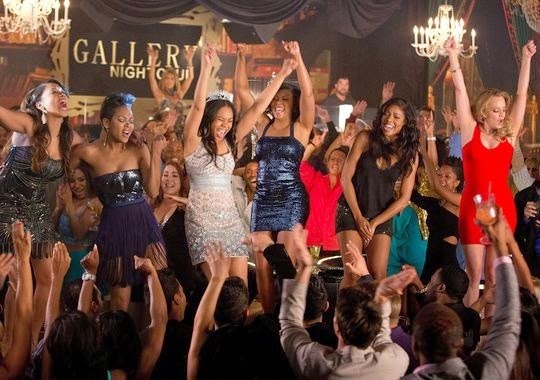

The fully three-minute plus rendition of Bell Biv DeVoe’s “Poison,” which the women perform from bar tops, VIP banquettes, and a fluorescent-lit room shot with a fisheye lens (a la Puff Daddy and Mase), was the climax of a ladiesBy the time that both parties reunite and resume their normative lives, the women have already exhibited their independence, having traveled back to the 90s in order to enjoy their present. Where that freedom will take the characters next is unclear, although I am confident that we will see them all again. Until then, it would be worth reimagining the premise of the films: instead of requesting that women Think Like a Man, I think (like a woman) that it would be a far more provocative and liberatory gesture to encourage men to Party Like a Woman.

***

Shana L. Redmond is Associate Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at USC. She received her combined Ph.D. in African American Studies and American Studies from Yale University. Her research and teaching interests include the African Diaspora, Black political cultures, music and popular culture, 20th century U.S. history and social movements, labor and working-class studies, and critical ethnic studies. Her book, Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora , examines the sonic politics performed amongst and between organized Afro-diasporic publics in the twentieth century. Her current project details the performative regimes of aid music.

Published on June 19, 2014 20:21

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.