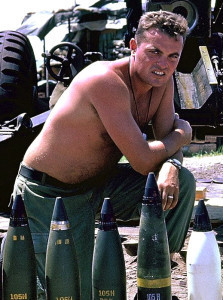

Dave Fitchpatrick – Gun Crew Chief – Part One

Dave Fitchpatrick

PART ONE

Dave On Duty

Courtesy Rik Groves

I was older when I went to Vietnam, 24 ½ years old with a wife and a kid on the way. Plus I had a degree in finance. They put me on Gun 3, the base piece. The crew chief was Emory Smith a career staff sergeant who fought in Korea. He was the prima donna of the battery and liked to party. He really didn’t want me. He wanted another fellow who could play the guitar. But the guy was a screw up, and they told Smith, “No, you want Dave because he’s older.”

A lot of guys on Gun 3 at the time had less than 90 days left in country, including Smith himself, which was lucky for me. He asked me, “Do you want to be a private your whole tour or a sergeant?”

I said, “A sergeant,” and he put me right away on the gunner’s sight. Normally a new guy had to hump ammo and cut powder charges, and couldn’t so much as touch the gun, much less work the sight. That’s where I did all my learning. I learned how to sling out the guns for helibornes and I trained a lot of new guys that were coming in. When Howie Pyle showed up I trained him how to be a gunner.

Two or three days after I got there we went on an air mobile operation along the coast with the 101st Airborne. There was no firebase that could reach them way up in the jungle. The only thing that could reach them were jets, and they were not in abundance at the time. Usually we took three guns and played hop scotch through the jungle with them. They would go so far and sweep, and we would drop the guns behind them. Then they would go further up and we’d come up behind them again. And we were fast; we could get something to them within 30 seconds. We did a lot of shooting but we didn’t get any incoming. A lot of fire fights, you could hear them in the distance, but we did not get into any direct combat ourselves.

All together I went on about four air mobile operations. I was fortunate, or unfortunate to go on that many, because that’s why I don’t know a lot of guys. When you’re gone a month or two and you have a new guy come in, then you go on R&R and you come back and he goes, so you could be there a year with somebody and not know him.

What You Never Learned in Training

There were things you didn’t learn until you got to Vietnam. Like the first time you’re mortared. It’s the worst thing ever. Your heart rate goes straight through the ceiling, you get dry mouth, and your adrenalin is going like hell. Then after that you almost get complacent, until one hits close to you. Then it starts all over again.

I’ll tell you something else that’s weird. When we were shooting H&Is rounds at night, you wouldn’t hear them when you were sleeping even when they shot them over your head. But I heard mortar rounds leaving the tube, could hear them before they hit the battery. It would wake me up. You could hear it leave the tube, that puff sound. It’s an eerie thing to wake up in a cold sweat and hear that thing and know it’s coming in. By the time you get up and react to it, it’s already hit.

Nobody ever got enough sleep at LZ Sherry. You were either on duty, on guard at night, under a mortar attack or shooting a mission. At night we used to have 50% guard, four guys on and four guys off. You could be on guard duty four hours, and then be up four hours shooting. So I would go sleep in someone else’s bunker, and when Top came around and said, “Where’s Fitchpatrick?” they’d say I was at the latrine. Top would look in my hooch and see an empty bunk and figure I was at the latrine. They’d quick sneak and get me and say Top was looking for me and I would get up and go find him. We figured there was no harm because you still had three guys up. That was our plan, and we worked it on a rotation system for guys to get a little more sleep.

You learned how to deal with cook offs. When we’d shoot so much on a long fire mission, usually at night, the tube would get so hot that when you loaded a new round it would fire as soon as you closed the breech. So you wanted to make sure you got the quadrant and deflection set before you loaded, and you’d better close it quick.

An Artillery High

You had to keep track of the temperature of the powder charges because it determined how hot the powder would burn, and FDC had to figure that into firing data. Base piece was used for registering all the guns, because it was in the middle of the “lazy W” configuration of six artillery pieces, so that’s where we measured the temperature. We always had a thermometer stuck into one of the canisters in the ready rack. That’s where we kept the rounds after we took them out of their shipping tubes ready to fire when a mission came in. All except the one with the thermometer of course. Knowing this someone decided to hide a stash of marijuana in there thinking it would be safe.

During a fire mission you grabbed rounds off the ready rack, set the fuse and got the round in the air as quick as you could. On this occasion, in the heat of battle, someone grabbed the powder temperature round off the ready rack. When it fired it made a funny sound. Sparks flew out the muzzle of howitzer and a cloud of sweet smelling smoke drifted over the battery. We never found out who it belonged to. Even so there’s not much we could have done about it, due to lack of evidence.