The Cat Came Back

Hello, friends. On Father’s Day, our family drove out to the United Church hall in the village of Battersea, Ontario, for a concert by children’s musician Gary Rasberry. It was a lovely afternoon with thoughtful and inventive music for children, astoundingly gifted musicians (including Sheesham Crow, from Sheesham & Lotus), and church-lady pie.

True story:

Me: May I have two coffees, please?

Church lady: That’ll be $4.

Me: Oh, and a slice of pie, too.

Church lady: Okay. That’s… $4.

One of the songs Gary & friends performed is “The Cat Came Back”. If the song is new to you, know that it’s a gleefully nasty folk song about the attempted destruction of an unloved cat. Despite dynamite, electrocution, guns, drowning, hot-air balloons, train wrecks and the mysterious disappearance of several humans, the cat prevails. It’s the kind of macabre thing that so many children love. Plus, it’s ridiculously catchy.

If you’re Canadian, you probably associate the song with children’s musician Fred Penner. (Here’s a recent-ish video of Penner performing “The Cat Came Back” for an audience of adults, many of whom probably grew up watching his TV show.) I’d always assumed that Penner wrote the song but at the concert, Gary and Sheesham mentioned that the song dates back to the American minstrel tradition of the nineteenth century.

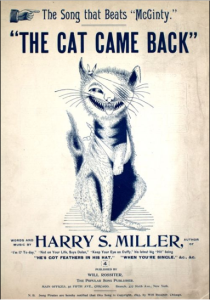

“The Cat Came Back” was originally published in 1893 by Harry S. Miller, but the first commercial recording seems to have been some 30 years later, in 1924. I really like the idea that the song got established in performance, both public and private (I picture a multi-generational family gathered around a slightly-out-of-tune piano and bellowing, all together, “It just wouldn’t stay a-waaaaay!”) before finding its way into the commercial music industry.

But here’s the main thing that I really must mention in the history of “The Cat Came Back”: Miller’s original lyrics are written in African-American dialect (Georgian, according to wikipedia), which means they feature non-standard grammar and creative spellings to signal pronunciation: “of” becomes “ob”, “yellow” becomes “yaller”, and “with” becomes “wid”. So the song isn’t just about an irate and desperate Mr. Johnson who will do anything to be rid of his cat; it’s about black dialect and a black singer. (I imagine Mr. Johnson is black, too, although that’s ambiguous.) A large part of the song’s comedy is predicated on black people saying and doing laughable things. Don’t believe me? Its original title was “The Cat Came Back: A Nigger Absurdity”.

I’m not suggesting that we should stop singing “The Cat Came Back”. That would involve cutting a hole in American folk music history. And the joke works perfectly in standard English, stripped of its racist context. But, as ever, we need to be alert and to remember all the peculiar and shadowy aspects of our cultural histories. Performers like Gary and Sheesham are slipping clues to the adults in the audience. And I’m grateful to have my horizons widened through an offhand comment at a children’s music matinée.