How to build the scary future today

Create a tiny computer using as small a chip you can get.

Create a tiny computer using as small a chip you can get.

Stick a Bluetooth LE or equivalent transmitter on it. Even better if you can get GPS. Even more if you can get a low power cellphone chip.

Call this a node.

A node has a unique id. Nodes get stuck on objects in a non-removable way. So basically, you have a ThingID.

A ThingID periodically pings for any ThingIDs that are near it, and remembers what they are. In other words, it’s a small mesh network of ThingIDs that are near each other. If a ThingID near another ThingID goes away, they both remember it and timestamp it. Maybe you can use signal strength to triangulate and get more precise locations.

When something more powerful comes by, like say a smartphone, it automatically gets all the data from the ThingID. It can also add stuff only it can provide – imagery, for example, or GPS coordinates, and upload those to the cloud.

The smartphone can of course use the ThingID to look up a ThingID (and therefore the object) in the database of ThingIDs.

Some ThingIDs are familiar – they cross-reference to VIN’s on cars, SKU numbers, or to social security numbers, or to taxi medallion numbers, or ASINs, or to serial numbers. The ThingID is just a unifier – these additional identifiers just all get associated into the master ThingID. So you can pull down whatever info is out there in databases related to that.

Some aren’t in there yet, but that’s OK. A ThingID is an instance id, you see, that then always cross-references to a template ID. Call that a TypeID. If a given ThingID doesn’t have a lot of data associated with it, you can always use it to instead go to the model number, or whatever. So any washing machine with a ThingID lets you pull up the manual for the TypeID on your phone as soon as you walk near it.

As annotations are added to ThingIDs, you’ll be able to get the service record too. And also stuff like its shipping history (since it was once near the ThingID for a shipping container, a customs scanner, and so on). If someone steals your object, odds are good you’ll even be able to map the trail it took away from your house.

After a while you start creating ThingID for virtual things too. Businesses, for example, so that you can swallow up Zagat and Yelp. A statue with a ThingID pulls up not only the entry for that statue, its sculptor, the date it was emplaced, etc, but also for the related ThingID of the historical event it commemorates. Then ThingIDs swallow Wikipedia (or maybe Wikidata first, then Wikipedia).

After a while you start creating ThingID for virtual things too. Businesses, for example, so that you can swallow up Zagat and Yelp. A statue with a ThingID pulls up not only the entry for that statue, its sculptor, the date it was emplaced, etc, but also for the related ThingID of the historical event it commemorates. Then ThingIDs swallow Wikipedia (or maybe Wikidata first, then Wikipedia).

A virtual space is created using data from ThingIDs, of course. You want to be able to geographically place ThingIDs into virtual datasets. The most obvious application is simple mapping, but that’s not that interesting.

More interesting is the notion of RealityIDs, which act as filters on ThingIDs. A given ThingID may or may not exist within a given RealityID; each is basically a different kind of view. So a tourist RealityID may not know about the ThingIDs for cars, but will readily display all the historical markers. You could create a RealityID filtered on a time range, for example, that only displays ThingIDs that were present within that timeframe. With this, you could walk around New York and be shown the ThingIDs that were around on a specific day, a specific hour.

You can also have RealityIDs that are purely virtual; the ThingIDs that they track aren’t real at all. The alien invasion of New York in a movie might be a set in a marketing or fan-centered RealityID. The building that was blown up can be looked at through the lens of its historical interest, its reviews, its engineering data, or the on-set commentary on how they made it explode in CG.

Some folks might choose to play games in the real world, using RealityIDs that overlay reality with ThingIDs for fantasy creatures, locations, etc.

Some folks might choose to play games in the real world, using RealityIDs that overlay reality with ThingIDs for fantasy creatures, locations, etc.

Various sorts of devices allow perceiving RealityIDs; you can attune your augmented reality glasses to a given RealityID as you walk around. Fancy ones even use the data to overlay visuals on top of what you see; you can simulate a given ThingID being present, so you can see how that couch would look in your living room by creating a temporary RealityID and saying “pretend that ThingID #9863258752135986 is at this location.”

Some are hardcore; they use full virtual systems, such as desktop monitors or VR goggles, to explore RealityIDs. The ones that have few ThingIDs in common with the physical world might still get called MMOs by the old-school players.

Of course, I neglected to mention that people have ThingIDs. They fit into RealityIDs too. You can backtrace them through too. You can annotate them with metadata, like say, their LinkedIn profile, or any one of multiple competing digital reputation systems (some hardcore folks might use Cory Doctorow’s “whuffie,” but most prefer eBay’s, or other vertical narrow reps, maybe). You can simulate them being somewhere too. You can choose not to display them in a given RealityID. You can surface one set of statistics about them in one RealityID, and a different set in a different RealityID.

All of this is basically running on exactly the same sort of dataset as what we used to use for just making silly online games… the way to build this future, you see, is to build a hell of a virtual world backend, and then start making every object be a c lient.

lient.

I am pretty sure that this is what multiple megacorps are currently working towards, though I am also pretty sure that most of them haven’t worked enough in virtual worlds to realize that’s how to do it.

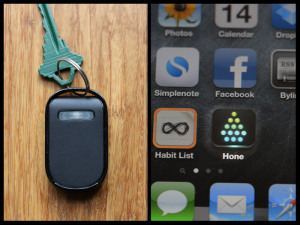

As soon as the price of a ThingID falls low enough, and it is about the size of a half-centimeter sticker, waterproof, flat, and basically calls for no power, I bet we stick them everywhere. After all, we don’t want to lose our keys.

Right now, ThingIDs are big and bulky. They are chips in pets, GPSes, RFIDs, and iBeacons.

Pretty sure they won’t be for long.