A Tale of the Drowned Moon

The Drowned Moon, or The Buried Moon, is a strange old tale from Lincolnshire. The best version is by Joseph Jacobs in his collection More English Fairy Tales (1894). Mine is a pale imitation but folk storytelling is a living tradition and its tales are meant to be told and retold so I’m retelling.

This tale is set in the Carrs – a flat, marshy area between the Lincolnshire Wolds and the Lincoln Cliff.

If you’re sitting comfortably, then I’ll begin.

Pity the traveller who finds himself out in the Carrs on a moonless night. Such paths as there are wind through bogs and around the edges of deep black pools, over tump and tussock, through sticky muck and alongside stinking streams. The lanterns of will-o’-the-wykes flicker far out across the marshes, luring the unwary to a watery doom. All else is a terrible dark and from this dark come things that creep and things that crawl, things that slither and things that grope and grab, screaming howlers, quicks and bogles, chill gobbins that suck the heat from your blood, long-fingered boggarts dripping weeds, snags that claw, rip and grip.

The Moon heard tell of these horrors. Being a kindly soul, she decided to find out for herself what evils oozed from the darkness on those nights when she did not emerge to brighten the night. So she wrapped a black cloak around herself to hide her light and out she went along the devious marshland paths.

She wandered far out into the bogs, with only starlight to guide her and with terrors all about her.

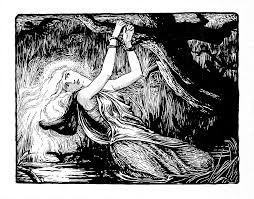

All was tarry dark. On and on went the Moon until at last she stumbled at the edge of a deep black pool. She snatched at a snag to stop herself falling in but as she gripped it so did it grip her, twisting its woody fingers about her wrists until she was held fast. All her struggles were to no avail; the snag had her and she could not break loose.

So she waited, starting at every slurp and suck and sigh and snarl out in the fathomless night.

Time passed and then came other sounds: panicky splashes, stifled sobs and fearful moans. Through the dark came a man, senseless with terror, blundering through mud and mire.

Kindly was the Moon so she twisted and wrenched and fought against the snag’s grip. Still she could not break free but her efforts caused her cloak to fall open. Her glorious silver light burned bright across the marshes, lit up the paths, chased the crawling things back into their dark places.

The man sobbed with relief. In his terror and haste, he gave no thought to the source of the light. He only fled back to the path, running as fast as he could in the direction of the nearest village.

Exhausted, the Moon slumped to the ground. Her cloak fell about her once again, and the pitchy dark flooded back across the Carrs.

Seeing their old enemy helpless, the horrors crawled out again from their hide-holes. They swarmed about her and filled the night with their screeches and howls and curses.

‘You!’ screamed the witch-bodies. ‘You broke all our spells with your moonbeams!’

‘You drove us into the cold black depths,’ hissed the boggarts, ‘and kept us there.’

‘We were hungry, always hungry,’ whispered the quicks, ‘because of you.’ And they whined so pitifully that the Moon would have been overcome by guilt had she not known that they hungered only for souls and warm blood and living flesh.

‘Smother her!’ cried the witch-bodies. ‘Smother her, smother her!’

Then all the night creeps joined in together, the gobbins and bogles, the quicks and boggarts, the necks and fetches, the ullerts and witch-bodies, until the marshes crackled with their howling chant of ‘Smother her! Smother her!’

By now, the dark was dimming in the east. The spiteful creeps gazed upon and knew they hadn’t much time before the first light of morning drove them back into the shadows. They crowded around the Moon, bent their bony fingers about her and hauled her down into the black pool at the foot of the snag. Then the bogles fetched a huge rock and dropped it upon her to keep her under the dark water forever.

As the sun rose, the horrors retreated into their pools and slimy crevices, their dank lairs among snag roots and under rocks.

The Moon lay buried under the rock, dead to all intents and purposes.

Days past. The time of the New Moon came but no New Moon appeared. The nights stretched black and empty from sunset to sunrise and the bog horrors grew wilder and bolder and no man, woman or child dared stray outside the villages after dark.

When the Carr folk could bear it no longer, a group of them went to the Wise Woman and asked her what they should do.

The Wise Woman gazed long into her cauldron and into her Magick Book. At last she said, ‘The dark has brewed so thick and deep that I cannot see what became of the Moon. Come back to me when you’ve got something more for me to go on.’

The Carr folk returned to their homes, for there was nothing more they could do. More days and more terrible nights passed and they hummed and hawed and puzzled among themselves whenever they gathered at the inn.

One such evening, a man from the other side of the marshes overheard their talk. All at once he slapped his mug of ale down on the table and stood up. ‘By my faicks!’ he exclaimed. ‘I reckon I know where the Moon lies hid!’

And he told them how he’d got lost in the bogs one night, all panicked and hounded by the creeping things, until a silvery light shone bright and showed him where the path was.

Back went the folk to the Wise Woman and told her what the man had told them.

Again the Wise Woman gazed long into her cauldron and long into her Magick Book.

‘The dark is still deep and sightless,’ she said at last. ‘But I’ll tell you what you must do. Leave just after the sun sets. Each man of you must hold a stone in his mouth and a hazel twig in his hand and speak not one word until you’re home again. You must go far out into the the marshes until you find a coffin, a candle, and a cross. Then look around you until you find the Moon.’

The next night, just after sunset, the men set off, each with a stone in his mouth and a hazel twig in his hand and no word uttered between them. Frightened though they were, they kept along the path. Deeper and deeper they went into the marshy wastes, and all along they heard squelchings and slitherings and eerie howls, felt cold breath against their skin and the scraping of bony fingers through their clothes.

At last they came to the black pool where the snag had caught the Moon. There they saw the rock that the bogles had brought to bury the Moon, lying half in and half out of the water and as long and as deep as a coffin. And upon it danced a will-o’-the-wyke, its lantern for all the world like a candle flame, and there above it was the snag with its thorny boughs outstretched like a cross.

The men searched all around, in the bogs and the slimy streams and among the tussocks, but there was no sign of the Moon.

One man peered down into the black pool and there, where the rock sat in the dark water, he saw the faintest glimmer of silvery light. He called the other men around and together they seized the rock and strained until their sinews tautened like ropes and sweat lay upon them like dew and they heaved the rock aside. For one brief instant a lovely face looked back at them and smiled. Then a great wash of silver light blazed out and dazzled them. When they shook the glare from their eyes and looked up, there was the Full Moon in the sky.

The Moon sent her shimmering light out across the bog lands to light up the paths and to chase the creeping horrors into the deepest nooks, as if she wished them as far away from her as possible.