Finding Fortune in the Walls of Delhi

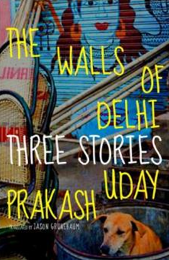

Uday Prakash’s THE WALLS OF DELHI: THREE STORIES

Uday Prakash’s THE WALLS OF DELHI: THREE STORIES

Are you paying attention to the fiction coming out of India these days? You should be, and I’m not talking about brushing up on the big-leaguer like Rushdie and Arundhati Roy (although, really, you should also read the full catalogues of both those names as well), but reading whatever you can get your English-speaking hands on. I don’t know what it is, but the whole ancient caste system’s place in this modern world and the impact it still – still – has on it’s stories, written in 2014, is absolutely fascinating.

Uday Prakash is no exception to this rule. He is, though, at a disadvantage; a Hindi writer, he relies on translators to get his words to English, but from what I’ve read, translator Jason Grunebaum did a fine job of transcribing Prakash’s latest short story collection, The Walls of Delhi.

A run down of the three stories contained here:

“The Walls of Delhi”: The title story, also the shortest. The tale of a simple street sweeper who finds a crack in the walls of Delhi, contained in which is more money than he could imagine. Never having resources like this before, he does what comes naturally: spends it as quickly as he can. By the time you get to the end of the piece, which, without spoiling for you, hands down the moral that the only way to make it in this bustling city is the find the money in the walls, it’s hard to separate what you’ve just read from the lyrics of an M.I.A. album.

“Mohandas”: You know how the ‘prince and the pauper’ trope is hard to translate into modern times? Eddie Murphy tried with “Trading Places,” which ultimately couldn’t do it fully; from a single glance, you can tell him from Dan Aykroyd. Here’s the thing: In India, where the caste system’s echoes are still in effect, this trope still resounds. In “Mangosil,” an Untouchable (contrary to how it sounds, Untouchable is not “Infallible,” Beyoncé-level flawless-ness, like “can’t touch this;” Untouchable literally means this person is so beneath the other levels, if you touch one you need to cleanse afterwards) is being targeted, hunted down because an upper-caste man is using his name and identity while committing crimes. The fun in most (good) prince-and-pauper tropes, though: It’s difficult to know which one will be dead in the end.

“Mangosil”: Hard to safely say, but probably the strongest story in the bunch. A child is born, to a poor family, with a strange medical condition that makes his head grow too big for his body. A virtual bubble-head, he learns to carry his head around with his hands as he walks. This great head is not just skull – from infancy on, this child is extraordinarily wise and insightful, and tragically serious. It seems as if he can read his parent’s thoughts, and even though, because of his illness, he is unable to attend school like his little brother can, the boy reads with a voracious appetite and create theories from these works that many adults never even bother to wonder about. He’s tragic, though – knowing his large head can’t be sustained forever, especially on his family’s budget, there’s a lingering fear each week could be his last; plus, on top of it all, this is a child dealing with MASSIVE topics like the oppressiveness of the English language. If you can read this story and not fall in love with the little boy, see a doctor, your heart is not working.

These stories are all so, so painful true to the human nature. Our flaws are exposed; faults and shortcomings shoved in our faces and forced to be looked at. At the same time, though, we are forgiven. We are pitied and adored and stroked like an infant all at once. They’re foreign, sure, but if you have a mind capable of metaphors, they’re the stories of you and your neighbors just as much as that of the characters.

Seriously, though: you finish each piece and it’s like a slap in the face of realization at what’s just occurred, and you can’t even feel the full sting until the next day or the next week when your mind has had some time to fully digest everything that’s happened.

These stories have sticking power.